SUBTLE music is having a moment. Maybe it’s not surprising: a quiet revolution of slow, careful, inconclusive sounds that speak, or whisper, against the noise and dogma of the times.

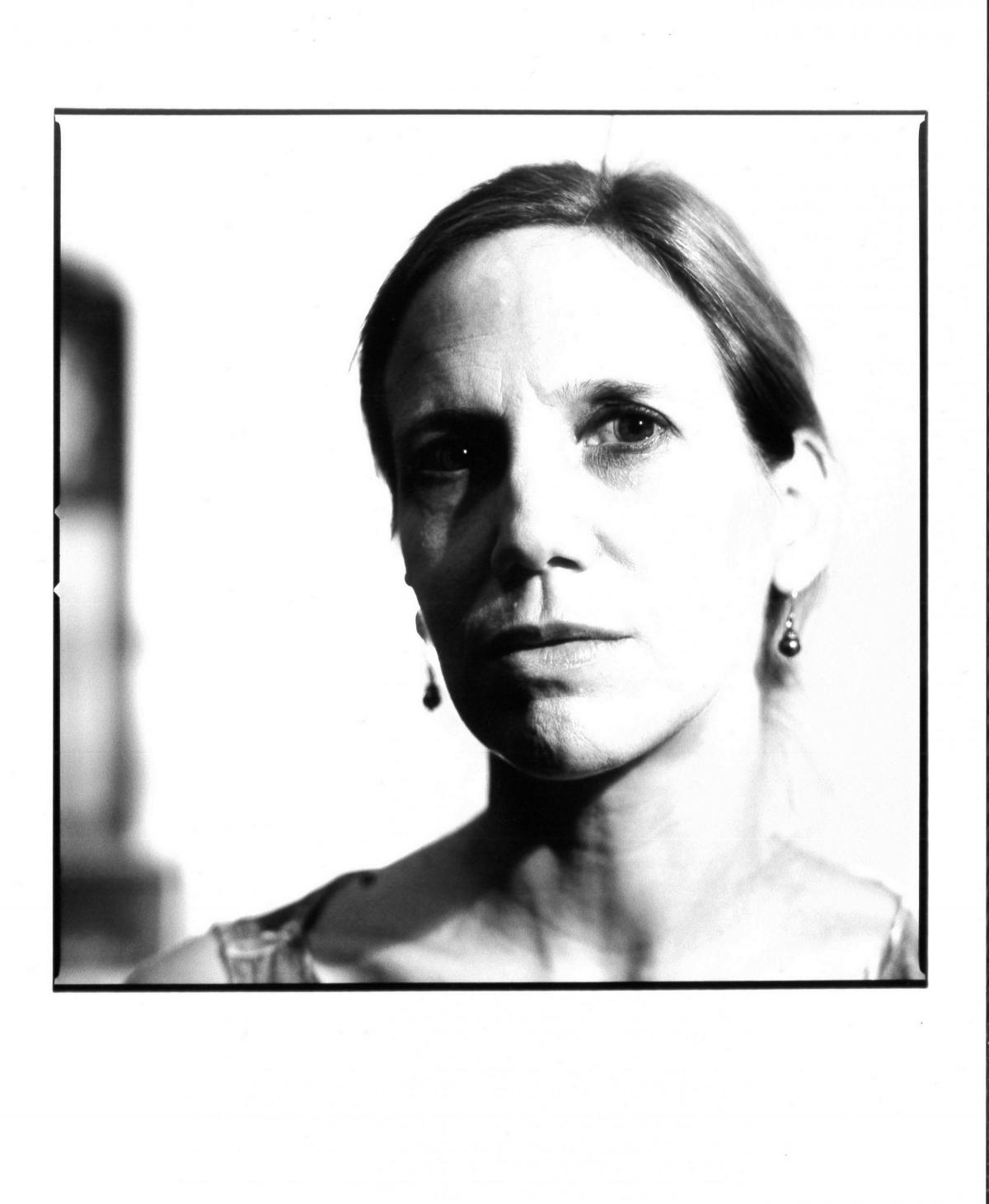

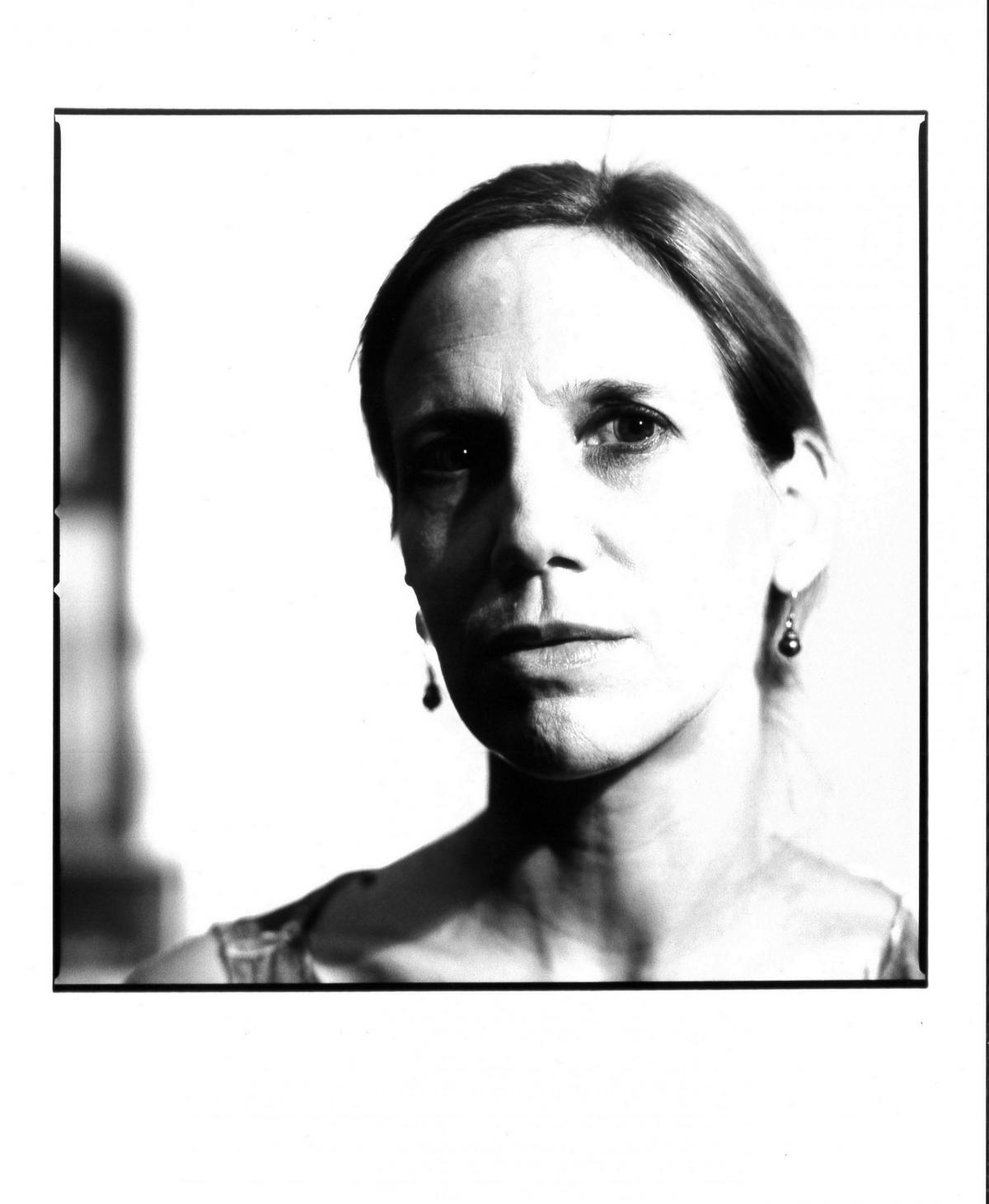

“Maybe people are wanting work that allows you space to just be with it,” suggests Linda Catlin Smith, a Toronto-based composer whose calm, clear music features at this weekend’s Tectonics festival in Glasgow.

Catlin Smith is part of what she calls a “lineage” of composers who spend their lives writing delicate abstract scores. A double album of her work was released recently as part of a major study on Canadian composers by the Sheffield-based contemporary music label Another Timbre. It’s a series that doesn’t so much try to define a Canadian school – and certainly doesn’t bother with any cliches about wildernesses or frontier mentalities – as link together composers who share a “similar art pad”.

That art pad is uncluttered, graceful, sparsely populated with fragile objects and beautiful spaces in between. “We talk about a meandering sensibility,” she tells me. “Not in an aimless way, but in a ‘we’re open to possibility’ way.”

Elsewhere, but interrelated, is the Wandelweiser group that includes Jurg Frey, Michael Pisaro and Eva-Maria Houben – composers who give such prominence to silence and fragility that at times their music seems about to blow away. UK-based composers like Laurence Crane, Bryn Harrison and David Fennessy do similar things with a more British sense of irreverence and self-deprecation.

It would be unhelpful to force too many shared attributes, but broadly speaking this is a kind of music without obvious narrative, without absolutist statement, happy to dwell on a single note or group of notes without hurry to get anywhere else. It’s pretty much the opposite of the ego-driven, juggernaught goal-orientation of a romantic symphony. “The experiment is always about whether something will hold,” says Catlin Smith. “I’m not making music that is about myself; I am making music so I can lose myself.” Music for our times, indeed.

The Tectonics programme includes several pieces by Catlin Smith, from solo to orchestral. Alison McGillivray plays a work for baroque cello called Ricercar, described by the composer as “a melody in search of its harmony”. The New York piano/percussion quartet Yarn/Wire plays Morandi, named after the Italian painter whose still life canvases “reveal a preoccupation with the same objects, in muted colours, painted over and over again”. And the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra plays two orchestral pieces.

“Both of them are me trying to immerse myself in the richest harmonies possible,” says the composer. Adagietto pays homage to the slow movements of baroque and classical orchestral music, their unhurried pace “allowing for more complex harmony to be heard”, while Wilderness explores colour. “It is a metaphor for taking myself somewhere new, putting myself in a situation and seeing if I can get out. It’s definitely not a portrait of some savage Canadian wilderness or anything like that.”

Catlin Smith is an ideal Tectonics composer. One of the top objectives of this festival is to reconsider how a symphony orchestra relates to contemporary music, to explore new ways of writing for and listening to an ensemble whose modern form was shaped in the 19th century. Some artists coming from outwith a mainstream classical heritage are sceptical of the infrastructure – the institutional privilege, the lack of creative freedom it allows individual musicians. But Catlin Smith says she’s only interested in the sonic potential.

“The orchestra? It’s a chance to work on a larger scale,” she sums up: like her music, her conversation has a considered, concise turn of phrase.

“I want to be immersed in sound and I can’t get that with chamber music.” Which doesn’t necessarily mean denser textures, but expanded versions of her lissom intimate works.

“There are a lot of threads, but the weave is loose enough that you can still see through it. What I love is the way an orchestra activates a larger room. The physical space it takes up. Yes, it’s expensive, but it’s like a painter saying, ‘I need the whole room’.”

A lot of Catlin Smith’s images come from visual arts. She talks of Agnes Martin, the Canadian abstract expressionist who has been the focus of extensive recent retrospectives at the Guggenheim in New York and the Tate Modern in London. Martin’s canvases are sparse, tough, meditative.

“You go there and sit and look,” was the advice she gave people coming to see her paintings, but it was also the way she made her work, painting the same thing over and over with subtle and infinite variations.

Similar tactics are at play in Catlin Smith’s music. Her own background goes back to New York: she was daughter of a piano teacher, schooled in alternative education with tiny classes. As a student she was enthralled by early John Cage, by the controlled textures of Japanese composer Jo Kondo, by the near-static long-form scores of Morton Feldman, by the spruce and shapely elegance of Couperin and Josquin des Prez.

“I was always drawn to people who were writing music that’s abstract and thoughtful rather than histrionic and bombastic,” she says. She also frequented pub sessions of Irish and Appalachian folk music. “I like things that repeat. I like modal harmonies and I like transparent textures. A lot of the harmonies and textures I use are left over from that sound.”

Now, like Martin, the way she works is all about sitting and paying attention. “I start concentrating on a sound, a harmony, and I pursue that. It’s not improvisation. I think of it as a ruthless contemplation. It’s not ‘anything goes’.

It’s more like a painter stepping back from a canvas and thinking, "Now what?”

Tectonics 2017 is Saturday and Sunday at City Halls and the Old Fruitmarket, Glasgow

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here