FOUR years ago a couple of experienced cavers, Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, ventured into a cave system known as Rising Star, less than three dozen miles from Johannesburg.

Part of their mission in exploring the caves was to see if they could come across any fossils of our early ancestors. Such things had been found in this part of South Africa before, so much so that it has become known as the Cradle of Humankind. The cave system has been described as the richest fossil hominin (the group of modern humans, ancestors and extinct human species) site in the entire continent.

Hunter and Tucker succeeded in reaching a stalactite-heavy cavity. Hunter wanted to shoot some video and in trying to squeeze out of the frame Tucker accidentally came across an extremely narrow chute. Both men entered it – and in doing so came across what National Geographic has termed as “arguably the most astonishing fossil discovery in half a century – and undoubtedly the most perplexing”.

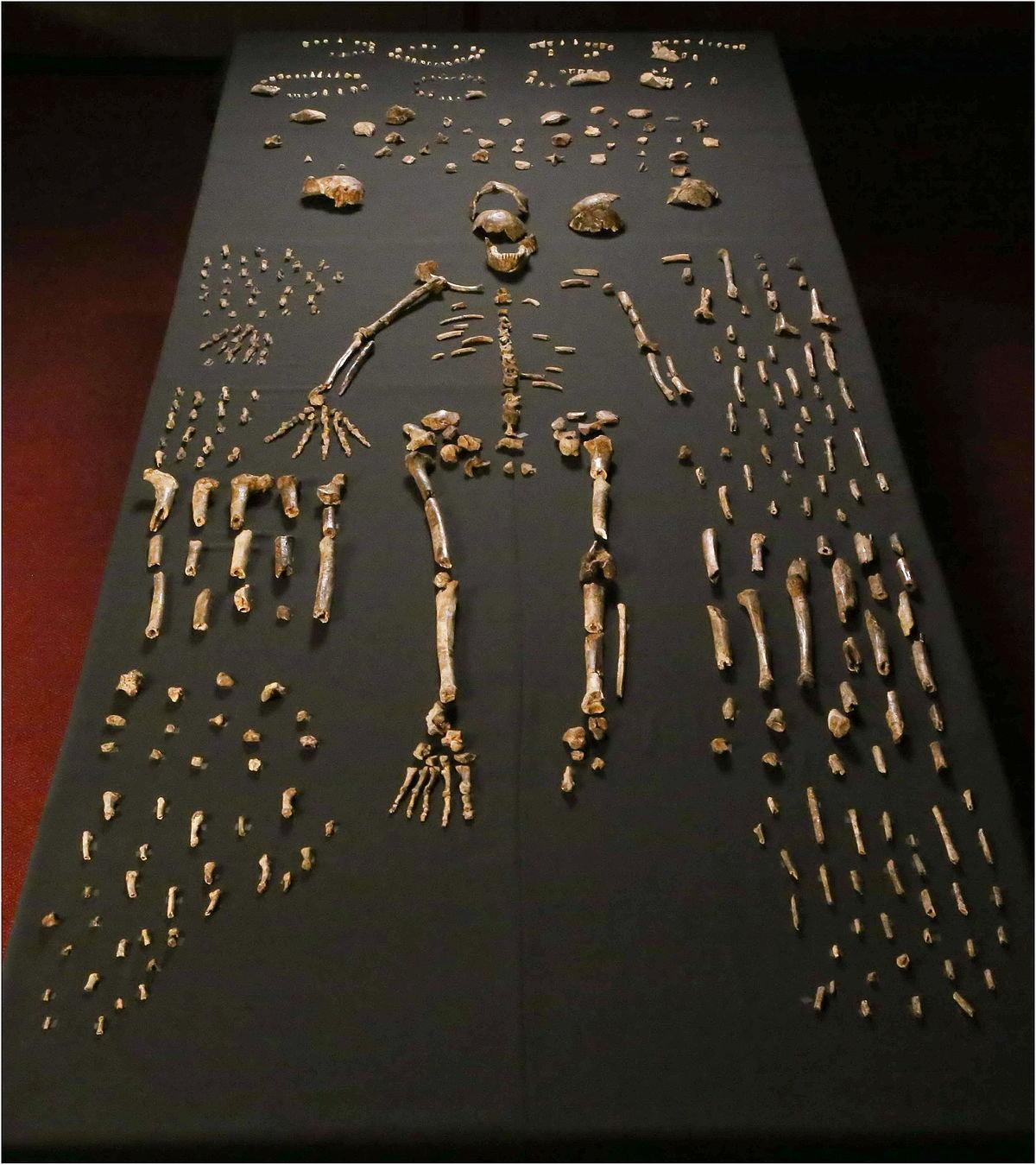

What the men eventually found in a chamber was a collection of bones, including a piece of lower jaw with intact teeth. The discovery enthralled Professor Lee Berger, a noted American-born South African paleoanthropologist, who quickly organised an expedition to excavate more than 1,500 hominin fossils.

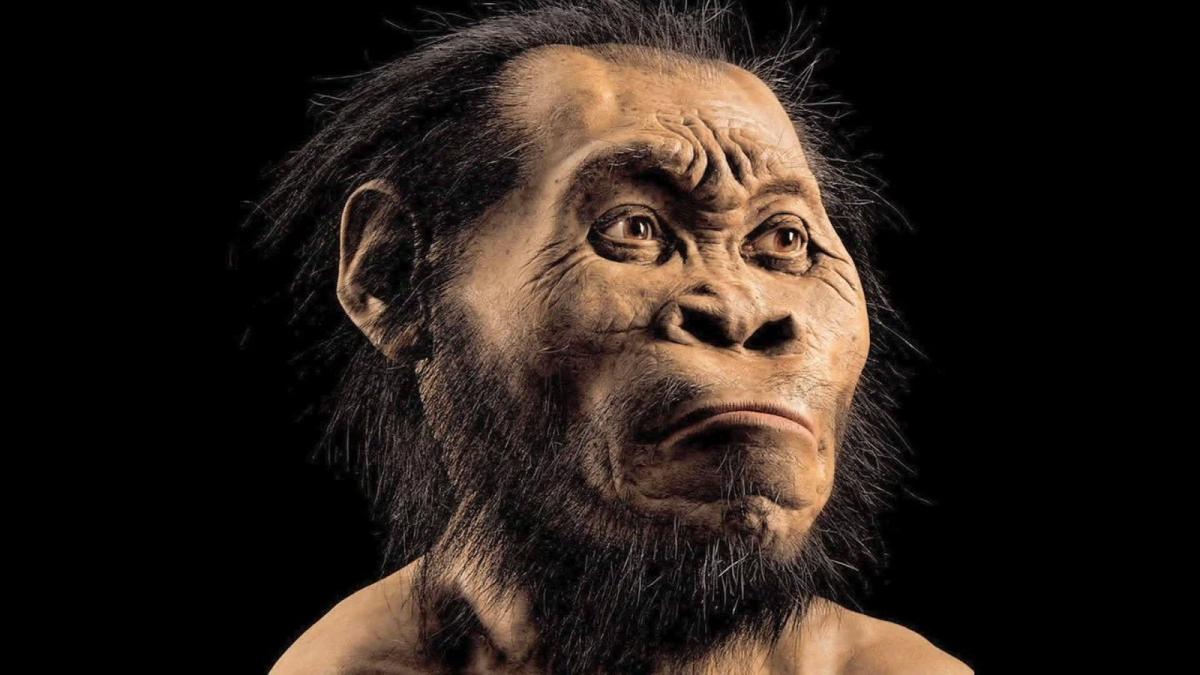

In September 2015 Berger and his team proudly announced the discovery of a new species of humankind, Homo naledi, named after the Dinaledi cave in which it had been found. It caused a huge international stir, even though for a variety of reasons the specimens could not be dated at the time.

Many in the field assumed that naledi was between one and two million years old, if not even older. But new dating evidence has revealed that the skeletons are in fact a mere 200,000-300,000 years old, which means primitive, small-brained hominins may have lived at the same time as the first modern humans in Africa. It is an astonishing assertion.

In a video posted online, Berger, of the University of the Witwatersrand, says: “This means that Homo naledi – this primitive hominid that appears to come from the root of the genus, homo – actually lived not only through the last several millions of years, but was contemporary with when we thought only homo sapiens lived on the continent of Africa.

“This is undoubtedly going to have a profound effect on our understanding of archaeology. In fact, it’s a little bit confusing because now we have at least two potential makers of these very complex stone industries which are scattered about southern Africa and perhaps the rest of Africa.” It is, he added, going to give rise to more questions than answers.

The discovery of a second naledi cavern, dubbed the Lasedi chamber, adds weight to the idea, Berger believes, that naledi deliberately disposed of their dead in a ritualised fashion in these deep, remote, underground chambers of the Rising Star system.

“Inside of this chamber are several individuals – some children, a couple of adults, one of which is now amongst the most complete skeletons ever discovered,” he said. This adult has been given the name of Neo.

Berger says there are “thousands” more remains in the Dinaledi chamber and probably many others in the Lasedi one. “So we have a great future ahead of us for discovery in these caves”, he adds.

Berger has also said that we can no longer assume that we know which species made which tools, “or even assume that it was modern humans that were the innovators of some of these critical technological and behavioural breakthroughs in the archaeological record of Africa … If there is one other species out there that shared the world with ‘modern humans’ in Africa it is very likely that there are others. We just need to find them”.

Naledi fossils have just gone on display at Maropeng, the official visitor centre at the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site.

A Washington Post article says some scientists not involved in the naledi research have “urged caution about some of Berger’s bolder claims”, including the burial of their dead and devising the sophisticated stone tools that make up southern Africa’s Stone Age.

The article added that ritual disposal of the dead is an advanced behaviour and that only humans and Neanderthals have been conclusively found to do it. Several scientists say the possibility cannot be ruled out that the bones were deposited in the cave naturally. But if naledi placed the bones in the caves for ritual reasons it would mean the species “was capable of something profound”, the article added.

There’s no masking the scale of the reaction, however, to the news that naledi is younger than had been hitherto suspected.

Late last month Dr Adam Rutherford, presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Inside Science, interviewed paleoanthropologist John Hawks, one of the naledi team. A few minutes before it began Hawks told him of the new age of naledi.

“My response was unbroadcastable, so I apologise for that”, Rutherford told Hawks on air. The actual age, he added, “is just breathtaking … We’re talking about a new species of human, very different from homo sapiens but present at the same time”.

The Dinaladi fossils, says Hawks, “are the age of Neanderthals in Europe, they’re the age of Denisovans in Asia, they’re the age of early modern humans in Africa. They’re part of this diversity in the world that is there as our species is originating”.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel