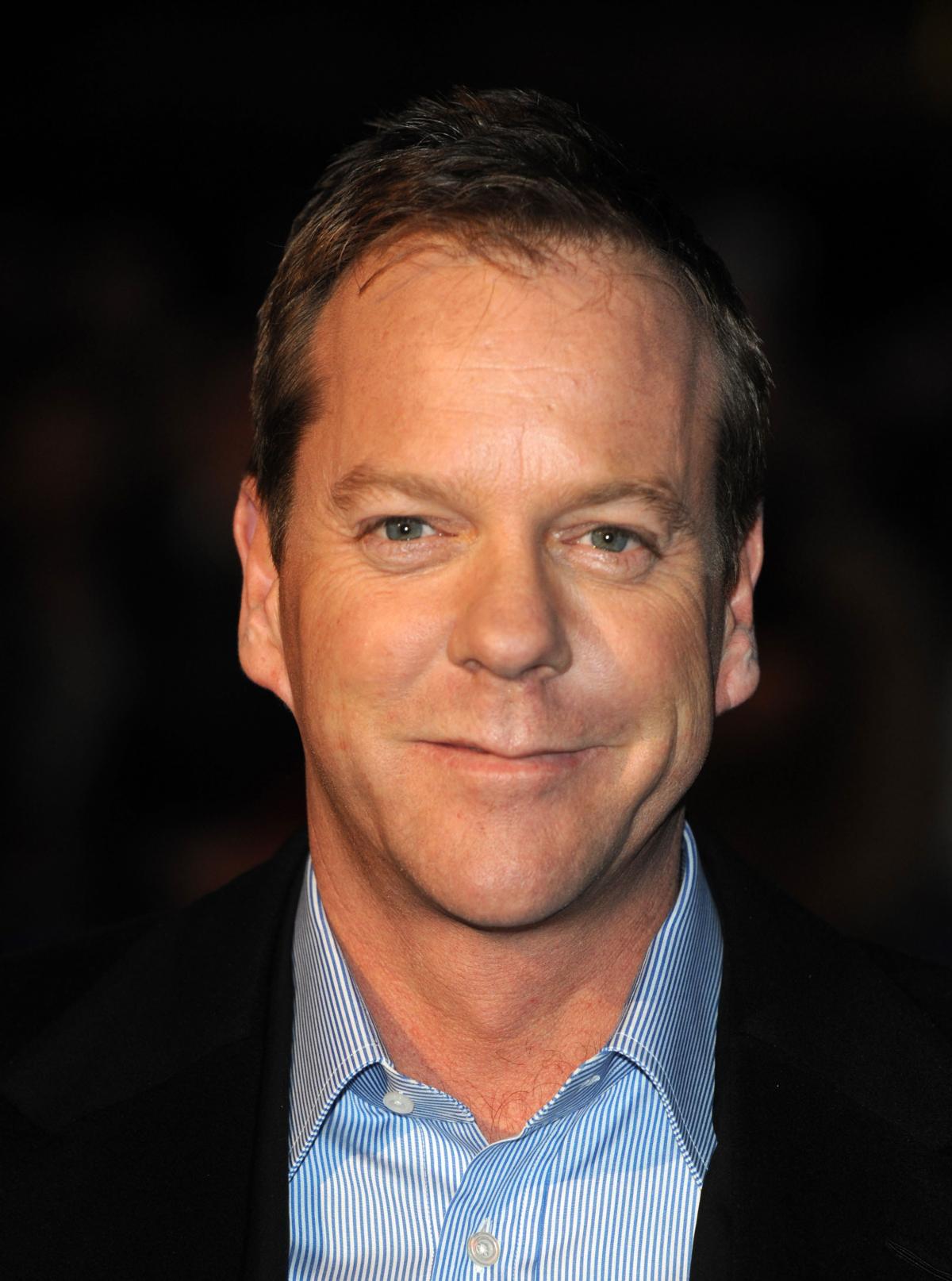

HE is acclaimed as the father of the Canada's version of the NHS, is the grandfather of 24 star Kiefer Sutherland, and has been hailed as the greatest ever Canadian – but Tommy Douglas was born right here in Scotland and is little known in his homeland. In fact, his story only came to light on this side of the pond as Canada celebrated its 150 birthday.

While he is rightly celebrated in his adoptive home as a pioneer of radical social health care, Douglas was a larger-than-life figure whose story could have come straight from the pages of a novel. From boxing champion to prominent politician, Douglas's life was not without controversy, including a dark side that included flirtations with an ideology closely associated with the Nazis.

Born in Camelon, Falkirk, in 1904, Douglas was the son of an iron moulder and travelled with his family to Canada in 1910 when they immigrated to Winnipeg. Before his family departed, the young Douglas suffered an injury to his leg which would later shape his view of medicine and lead to the revolution of healthcare in Canada.

Plagued with osteomyelitis (a bone infection) in his right knee, Douglas underwent a number of operations but his parents were eventually told his leg would have to be amputated.

However, a well-known orthopedic surgeon took an interest in his case and agreed to treat the boy for free if his parents would allow medical students to observe and the leg was saved.

Many years later, Douglas told an interviewer: "I felt that no boy should have to depend either for his leg or his life upon the ability of his parents to raise enough money to bring a first-class surgeon to his bedside."

The family would remain in Canada until the outbreak of the First World War, when they returned to Scotland. Douglas dropped out of school once back in his native land aged just 13 and worked as a soap boy in a barber shop, and then in a cork factory.

Returning to Canada in 1918, he began an amateur boxing career and fought for the Lightweight Championship of Manitoba, winning the title after a six-round fight despite a broken nose and the loss of some teeth.

He also witnessed the Winnipeg General Strike, and while perched on a rooftop saw police charging strikers with clubs and guns. One worker was shot and the incident would was said to have had a deep impact on the young Douglas, giving him a commitment to protecting fundamental freedoms.

While this would be enough life for some people, Douglas was just beginning – at the age of 19 he decided to become an ordained minister and enrolled in college, where he was greatly influenced by the Social Gospel movement, which combined Christian principles with social reform.

He studied socialism, and paid his way through college by taking preaching jobs, where he spoke of "building a society and building institutions that would uplift mankind".

He also met his future wife Irma Dempsey, a music student, and had a daughter. That daughter grew up to be actress Shirley Douglas, who in turn married one Donald Sutherland, the film legend who starred in supernatural thriller Don't Look Now. We probably don't need to connect the dots, but in 1966 that Hollywood power couple gave Tommy Douglas a grandson named Kiefer, better known as Jack Bauer to 24 fans the world over.

However, long before he became a grandfather, Douglas had delved into the philosophy which would stain his character for years to come. In his university thesis, entitled The Problems of the Subnormal Family, Douglas endorsed eugenics. In the work, he charted the lives of a dozen “immoral” and “non-moral” women and their 200 descendants in his hometown of Weyburn, Sask in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. To Douglas, they were those “whose mental rating is low, ie anywhere from high-grade moron to mentally defective,” “whose moral standards are below normal,” who were “subject to social disease,” or who were “so improvident as to be a public charge".

In the thesis he also included recommendations to cleanse the genetic pool by improving marriage laws to certify a couple's fitness to procreate, the “segregation” of the subnormal populace through forced incarceration and institutionalisation and the state-sanctioned sterilisation of the genetically and intellectually “defective.”

“It is surely,” Douglas wrote, “the duty of the state to meet this problem.”

In 1935, only two years after writing his thesis, Douglas was elected to the House of Commons. He went on to become premier of Saskatchewan province, and would introduce North America’s first universal health care program, which would act as a model for Canada’s Medicare system.

He never introduced the ideas in his thesis into public policy, and historians believe he abandoned them after coming face to face with the end result of such thinking during a trip to pre-war Germany, where he saw first hand the Nazis' attempts to manufacture a “master race".

As an ambassador to a World Youth Congress in 1936, Douglas wrote he experienced a "frightful” epiphany after attending one of Adolf Hitler’s mass rallies.

The stain on Douglas's reputation has been confronted by Canadians, who have made their peace with it.

In a 2012 essay in The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, Dr Michael Shevell, head pediatrician at Montreal Children’s Hospital, wrote that Douglas’s eugenic episode should act as a warning, that even the best of intentions can go down a dark path.

However, Dr Shevell wrote, he thought it would be “self-defeating” for the nation to taint his qualities of compassion and equality by “lapsed judgments”.

Douglas rarely mentioned his thesis later in his life, and his government never enacted eugenics policies, even though two official reviews of Saskatchewan's mental health system recommended such a program when he became Premier and Minister of Health.

As Premier, Douglas opposed the adoption of eugenics laws and implemented vocational training for the mentally handicapped and therapy for those suffering from mental disorders.

Douglas would serve as premier until 1961 and aside from his healthcare reforms, created Canada’s first publicly-owned automotive insurance service, passed the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, became the first head of any government in Canada to call for a constitutional bill of rights. In 1962, he was elected into the House of Commons and remained there until 1979. In 1981, he was invested into the Order of Canada, and became a member of Canada’s Privy Council in 1984. He died in 1986 in Ottawa. All in all it wasn't bad for a boy from Camelon.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel