COMPLETE the following sentence, I say to Andrew Garfield. “Home is …” It’s the last question I ask the actor and the first time in our short conversation that he hesitates. “Home is … oh, home is … a new concept for me.”

Really? You’re 34, Andrew. In what way is it new? “Today I did my final exchange for my first home.” Ah, right. And on which continent might that home be? “It’s in the UK,” he laughs.

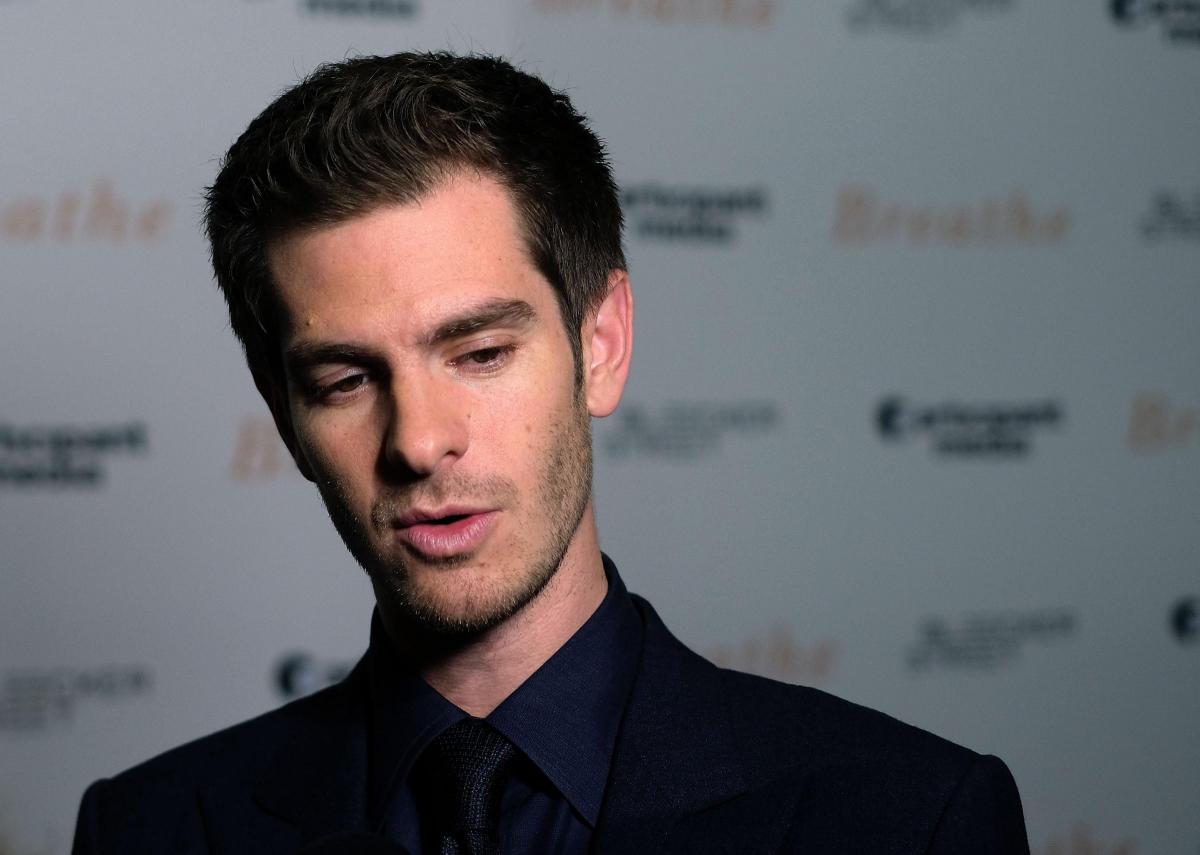

Friday morning, earlyish and Andrew Garfield, actor, sometime surfer, last-but-one Spider-Man, has a film to sell. He’s very good at it. Talk to him about Breathe, fellow actor Andy Serkis’s directorial debut, and he is eloquent and engaged.

To be fair he’s eloquent and engaged on most subjects, but such is the transactional nature of the celebrity interview, there are moments when he zealously polices the borders of the conversation and ensures it doesn’t stray too far into areas he does not want it to; you know the kind of thing – personal stuff, relationships, or the location of his first mortgageable property (actually, will he even need a mortgage?).

Yet in many ways it’s hard to imagine an interviewee who is so open about what he thinks and believes. Open to the point of naivety some might say. Or maybe open to the point of: “I don’t give a fig what anyone thinks.”

Anyway, the new film. It’s based on the true story of disability advocate Robin Cavendish. Garfield plays Cavendish, who is diagnosed with polio aged 28 and told he has three months to live. Helped by his family and friends, most notably his wife Diana (played with can-do stiff upper lip by Claire Foy), he defies that prediction by around 34 years. And he doesn’t just survive; he lives.

“It’s a tricky thing doing press,” says Garfield. “But I’ve loved talking about Robin and Diana, thinking about them, staying in their energy sphere and continuously squeezing wisdom out of their lives.”

This is what I mean. Garfield’s default setting is a wide-eyed engagement with the world. Asked why he wanted to make the film, he says: “I read the script and found it so moving and life-affirming and I thought: ‘What better way to spend my time than make a story about these two remarkable people and their friends that made such meaning and such beauty out of difficulty.’

“It felt universally relatable. We are all beset with certain challenges. It felt like a guidebook of how to incorporate that into our experience. And then make lemonade out of it, make joy, make progress, change the world inadvertently because of your longing to live.”

Serkis’s film is an old-fashioned thing, but the central story is undoubtedly affecting in the way it goes from a deep, dark place towards the light.

The real-life Robin Cavendish, who needed a mechanical ventilator to breathe, defied medical advice by leaving hospital after a year, and freed himself from being bedridden by working with his friend, Oxford University professor Teddy Hall, to develop a wheelchair with a built-in respirator. He then worked tirelessly to help people like him live fuller lives.

In the film, Garfield – immobile from the neck down – animates the screen with his wide grin. “[Robin] goes through all the stages of grief,” says Garfield. “It’s denial, anger, surrender and letting go and then depression. And at the bottom of himself he finds this hope.

“Underneath that feeling of loathing and feeling victimised; that the universe is unfair and that if there is a God then God is unjust, he finds out with the help of his wife that he still has this spark of life in him and he says: ‘Get me out of here.’

“There’s still part of him that wants to be in the world and if he’s going to be in the world he wants to be at home with the people he loves. He doesn’t want to be imprisoned as it were.”

In this respect, Breathe fits perfectly into the Andrew Garfield filmography. Look back over the movies he’s made since his breakthrough year of 2010 when he appeared in both David Fincher’s Facebook biopic The Social Network and Mark Romanek’s dystopian SF thriller Never Let Me Go and, with the exception of the two Spider-Man films, you can see a clear desire to tell deep stories; stories about how we exist in this world, what we believe in (his last two films – Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge about the pacifist combat medic Desmond Doss and Martin Scorsese’s Silence – both dealt with the way religious belief can conflict with lived experience).

Breathe asks what it is to live a life when your body betrays you, when you have no control over your external limbs. In short, is that a life worth living? The answer is a resounding yes, the film suggests.

“I think Robin was forced into surrendering his preconceived notions of masculinity and power and strength and being of value and what a strong man was,” Garfield continues. “I think he came to understand that what it is to be a strong man is allowing yourself to be helped, allowing yourself to be at the mercy of other people, allowing yourself to need a community of people, allowing yourself to need a strong woman in fact.”

How would the actor have coped in Robin’s situation? “You never know until you are faced with things. But I’ll tell you this, when I read it I thought I wanted to know how he did it. I wanted to be able to viscerally understand as close as possible how they created this life and how they were able to be so vividly alive with such a difficult situation.”

Is he telling me that on set he basically let Claire Foy do everything for him? “Hah. As much as possible. She would get very irritated. But she loved it as well. We really wanted to be this symbiotic creature.”

Garfield isn’t interested in talking about the technical challenge of only being able to move his head. “Because it is obviously an emotional art, acting, and even though my body wasn’t of use I had to be able to access my heart, I suppose.” There’s that wide-eyed open candour again.

The first time I noticed Garfield was in Channel 4’s 2009 adaptation of David Peace’s Red Riding trilogy, a bone-hard vision of 1970s Yorkshire noir in which he played a young newspaper reporter. Back then, the pre-fame Garfield was in his early 20s still finding his feet. Does he remember that version of himself?

“Oh yes. He was searching. On that job I had to find a lot of backbone for reasons I won’t go into. That was a good example of a tricky experience that taught me a lot about my own boundaries. I did some growing up on that TV film.”

There is a statement that is both frustrating and fascinating. But Garfield is already back to considering how he might have changed.

“I do recognise him. I’ve changed quite a lot, I hope, but also I see someone who was really devoted and wanted to make the character as truthful as possible and fight for what I believe was right.

“And I was maybe a bit more reckless and out of control and a lot more insecure in myself and what I was doing. But it was kind of raw, I suppose.”

Born in Los Angeles, Garfield moved to Epsom in Surrey with his family when he was three. He had a comfortable middle-class upbringing and went to a private school. But that school was difficult. He was small and has spoken before about being bullied. When he was cast as Spider-Man he told a comic convention: “I needed Spidey in my life when I was a kid and he gave me hope!”

These days he is a little more comfortable in his skin. A little. “I don’t think I’ll ever fully get there,” he says. “I hope not anyway because I think you start to die a little bit when you think you’ve got it all figured out.

“It’s endless, the searching and the mystery; the mystery of being here. I think that’s why I’ll always be an actor.”

Is that why he started? “I don’t know. I’d done sports as a kid and that was what really excited me; sport and playing the fool basically. In my teenage years I got more introspective and started asking those existential adolescent questions about what actually are we doing here and what’s the point of all this?

“I wasn’t getting any answers from my school system. Everyone tried but no-one could fix it for me. I was very confused and very anxious. I didn’t really get what the point was of life. Or what my point was anyway.

“But I tried acting in a school play and you know that moment when someone wakes up? You go: ‘Oh, wait a minute. There’s some light here and I’m going to follow it’. And I think that’s what I’ve been doing since then.”

In a way, Garfield’s dreaminess made him perfect casting for Spider-Man. It also proved problematic for the actor when he found himself at the eye of a media storm. The fact he was going out with his on-screen partner Emma Stone in real life at the time just amped up the wattage. (They are no longer an item.)

After the poorly-received sequel, The Amazing Spider-Man 2, Garfield spoke out against studio interference with the script. (There were even stories that the powers that be wanted to pluck his eyebrows.) There were stories, too, that he had lost the part after failing to turn up to a promotional event in Brazil. Tom Holland was cast in this year’s Spider-Man film.

“What I’ll proudly say is that I didn’t compromise who I was,” Garfield told the Guardian last year, talking about the sequel. “I was only ever myself. And that might have been difficult for some people.”

Playing Spider-Man was “a wonderful opportunity”, he says now. “It created this space for me to then make the choices I made after. I had a lot of opportunities to follow my gut and my heart and wait for the right things to come along.

“It also gave me a perspective on what was important to me. I learnt a lot of things on that job that felt really good and felt not so good. I tried to be as aware as possible about where I was supposed to be as an actor, what kind of stories I was supposed to be telling.”

He doesn’t elaborate but you could interpret that as saying the two Spider-Man films weren’t the kind of stories he wanted to tell. It also made him a public figure in a way he hadn’t been before. He is still coming to terms with that, he admits.

“I’m realising it’s like a proper intimate relationship between actors and audiences and like any relationship it takes work if you want to sustain it. And I do. Doing a film like Spider-Man creates a very specific kind of relationship which is not as interesting to me as the relationship that I’m trying to create with the world and with an audience now.

“I like having deep conversations. I like asking hard questions about what we’re doing here. I like conversations that wake me up.”

It’s almost time to go. Andrew, I ask, what makes you happy? “What makes me happy is doing things in the morning that are good for me like dancing or listening to music or going for a walk and talking to strangers.”

And what makes you angry? “What makes me angry is talking to a stranger and realising they’re not really listening to me because all they can see is the guy who played Spider-Man.”

Breathe is in cinemas now

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here