JEREMY Corbyn began the year under a political cloud.

The poll ratings were bad, Labour was languishing 13 points behind Theresa May’s Conservatives, Labour MPs were hoping for a reboot while even Unite’s Len McCluskey, Mr Corbyn’s staunch ally, confessed if the dire poll ratings continued into 2019, then his comrade might have to step aside ahead of the next General Election.

An indication to some that Labour was facing years in the Opposition wilderness and the Left was tightening its grip on the party came in January when Tristram Hunt, its former education spokesman, resigned to take over the directorship of the V&A Museum in London. An exodus of disgruntled MPs was predicted but never materialised.

In a keynote speech, the Labour leadership’s ambiguity on Brexit was laid bare early on when Mr Corbyn made clear his party was "not wedded" to the freedom of movement of people but also insisted he did not "rule it out" if it meant maintaining access to the European single market.

Internal problems on withdrawal were also laid bare when Clive Lewis resigned from the Shadow Cabinet over the leadership’s decision to whip MPs into voting to trigger Article 50.

By late February, tensions were mounting as two by-elections were fought. Defeat in both could have placed a serious question-mark over Mr Corbyn’s future. Stories suggested as polling day neared, the Labour leader was being kept away from the stump in Stoke-on-Trent Central.

In the end Labour’s Gareth Snell saw off the threat from the Tories and Ukip with a 2,620 majority. But in Copeland in Cumbria, the Opposition suffered a big blow as the seat, which had returned a Labour MP since its creation in 1983, went to the Tories. It was a famous victory as it was the first gain by a serving government in a by-election for 35 years.

A few days later in Perth at the Scottish Labour Party conference, Mr Corbyn made clear he would soldier on, declaring: “Now is not the time to retreat, to run away or to give up.”

But it was on Scotland and the SNP’s desire for a second independence referendum that the Labour leader sparked controversy when he suggested it was “absolutely fine” for Scots to hold another vote on the nation’s future.

While Mr Corbyn stressed how his party was against the notion of indyref2 and any vote should be put back until after Brexit, he also noted: “I don’t think it’s the job of Westminster or the Labour Party to prevent people holding referenda.”

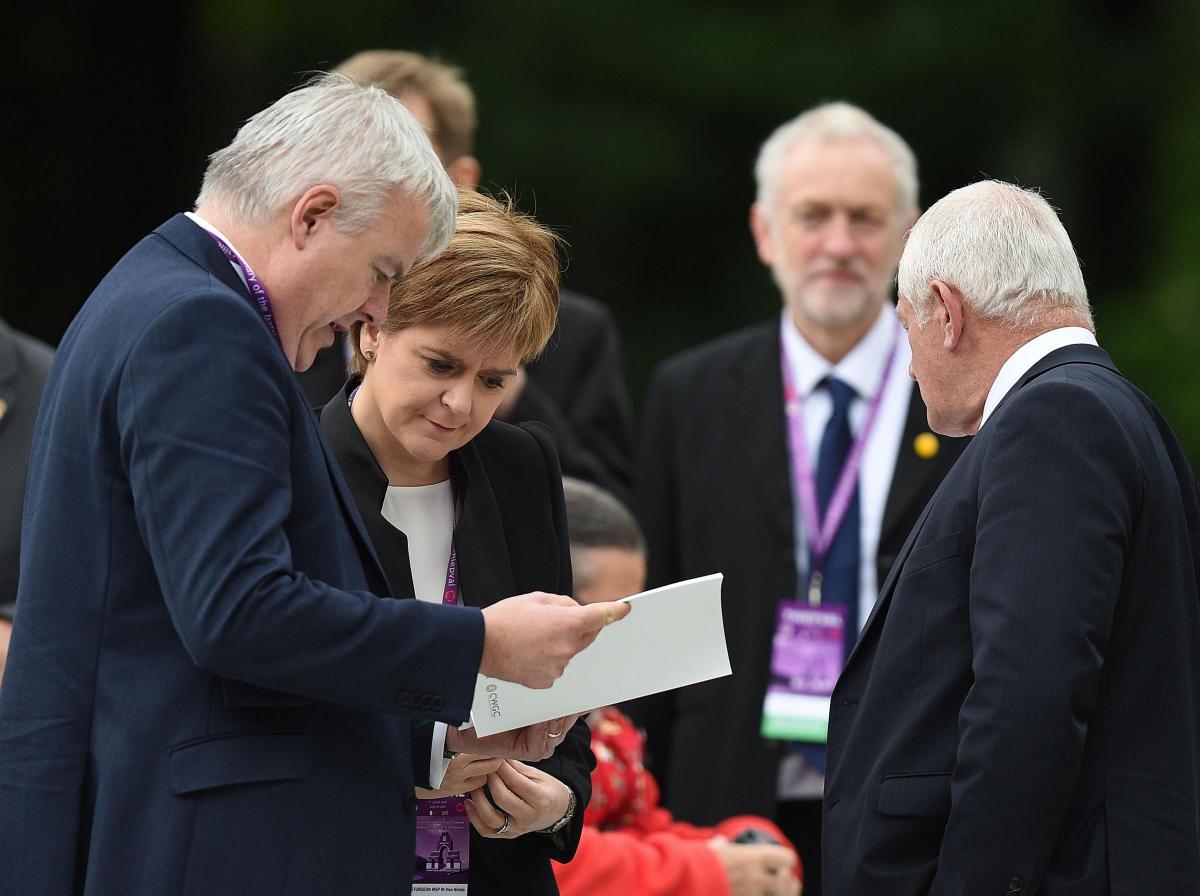

Nicola Sturgeon gleefully took to Twitter, declaring: “Always a pleasure to have @jeremycorbyn campaigning in Scotland.”

Kezia Dugdale, the Scottish Labour leader, who staunchly opposed a second independence poll, was incensed. Tory HQ, which had so effectively used the possibility of a Labour-SNP axis in the 2015 election campaign in England, reignited the fears south of the border.

By the second week of April Labour fortunes looked bleak as polls put the Tories more than 20 points ahead.

The Easter recess provided a welcome respite. But it also produced something else.

The day after the long holiday ended on Easter Monday, the Prime Minister stood in Downing Street to announce a snap June 8 General Election. Westminster was shocked. It was a fateful decision.

Initially, the Tories appeared relaxed by Mrs May’s dramatic change of heart.

Labour’s opinion poll ratings were dire, the party appeared confused over Brexit and Mr Corbyn’s leadership was again under serious question. By the time of the May local elections in England, which saw the Conservatives gain 563 seats and Labour lose 382, Tory HQ felt the road to another General Election victory was secure.

Yet as the Maybot progressed towards polling day, her inability to catch the public imagination or even connect with ordinary voters began to materialise. Her decision not to engage in live TV debates was ridiculed and her insistence that she wanted instead to meet ordinary punters rang hollow when it was a rarity to see her talk to anyone on the stump.

In contrast, Mr Corbyn, who had been steeled through two successive and successful Labour leadership campaigns, positively blossomed during the campaign, drawing large crowds and exuding a public confidence that had hitherto eluded him.

Labour’s “for the many not the few” manifesto launch at Bradford University, surrounded by young people, proved a populist hit and included scrapping tuition fees, renationalising rail and water, upping taxes for the better off, ending zero hours contracts and guaranteeing the triple lock for pensioners.

The Tory manifesto launch, also outwith the Home Counties in Halifax, proved a disaster with the now infamous “dementia tax”. The Tory lead was beginning to fall from its heady 25-point lead to the mid-teens.

Perhaps an indication of a Conservative wobble came when Boris Johnson, while on the stump, denounced the Labour leader as a “mutton-headed old mugwump”. Mr Corbyn laughed it off.

As the Labour leader traversed the country, holding public meeting after public meeting, arguably his worst moment came when he appeared to forget the cost of a key Labour childcare pledge during a tense interview on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour. However, it paled against Diane Abbott’s “train-crash interview” on Labour’s police recruitment numbers, which she later put down to being ill.

Arguably Mr Corbyn’s best campaign moment came when he decided to do his own U-turn and appear personally in a live TV head-to-head of leading opposition figures, thus highlighting the PM’s absence from public debate.

When the result was finally announced there was as much surprise within Labour ranks as anywhere else as the party gained 32 seats. The Leader of the Opposition called for Mrs May to resign when it emerged she had lost her majority. As she cobbled together a deal with the Democratic Unionists Mr Corbyn insisted he could “still be Prime Minister” as the future of the Tory administration looked far from strong and stable.

The so-called “Corbyn surge” was put down in large part to the Labour leader’s positive outlook, which appeared to resonate among younger voters. In Scotland, where the party leadership was said to have targeted just three key seats, Labour revived from their disastrous showing in 2015 to gain a total of seven.

Crucially perhaps, Labour’s rebels were eating humble pie and even going back into the Shadow Cabinet. Mr Corbyn’s grip on the party was even more secure.

As the polls for the first time put the Labour leader ahead of his Tory rival, he was put on the back foot over his pledge to “deal with” student debt, which many took to mean his party in government would write it off. But when it was calculated that this could cost up to £100 billion, Mr Corbyn and his colleagues insisted that they would only seek to find ways to lower the debt burden.

The Labour leader spent most of summer on a grand tour of Britain and even managed a speech at the Glastonbury Festival, where revellers chanted “oh Jeremy Corbyn”, which would become his signature tune at any subsequent public event.

As he repeatedly urged Mrs May to call another election, the Labour leader supposedly said privately that he expected to be in Downing Street by Christmas.

Underlining the importance of Scotland to Labour’s Downing Street ambitions, the leader spent a week here, admitting Scotland now “holds the keys” to him getting into No 10.

When Ms Dugdale unexpectedly stood down, the ensuing leadership contest pitted leftwinger Richard Leonard with centrist Anas Sarwar. While the union-backed Mr Leonard denied he was Mr Corbyn’s favoured choice, everyone knew he was and so the UK leader’s office was delighted when Mr Leonard was crowned leader.

At an enthused party conference, Mr Corbyn declared Labour was “now the political mainstream” and suggested it was on the “threshold of power”.

But the row over claims of anti-Semitism in the party and his suggestion that there could be a run on the pound if Labour took power were gifts to his Tory opponents during the conference season.

Just as the Conservatives were riven by differences on Brexit, so too was Labour as the party sought to keep happy the Remain and Leave factions in its ranks. But the elasticity of policy seemed hard to defend as the party leadership gave mixed signals on staying in the single market and customs as well as on the subject of a second EU referendum.

Sir Keir Starmer, the Shadow Brexit Secretary, seemed to be easing the party towards the softest of Brexits as he suggested nothing should be off the table and that Labour was in favour of a “single market variant” with full access to it, “a” customs union and “easy” rather than free movement of people.

As the year ended and both the main parties were embroiled in the sexual harassment scandal and Mrs May rode the Brexit rollercoaster, including suffering a key Commons defeat on giving MPs a “meaningful vote” on the final deal.

Yet her triumph in securing agreement on phase one of the Brussels talks helped the Tories regain some equilibrium as the polls put them neck and neck with Labour.

As for Mr Corbyn, who moves into his 70th year in 2018, he insisted he was fit and healthy enough to continue to lead Labour and be Prime Minister in the years ahead.

His secret? “I eat porridge every morning; porridge and energy bars and I keep off alcohol and meat. I've got loads of energy.” If 2018 is anything like 2017, he’ll need it.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel