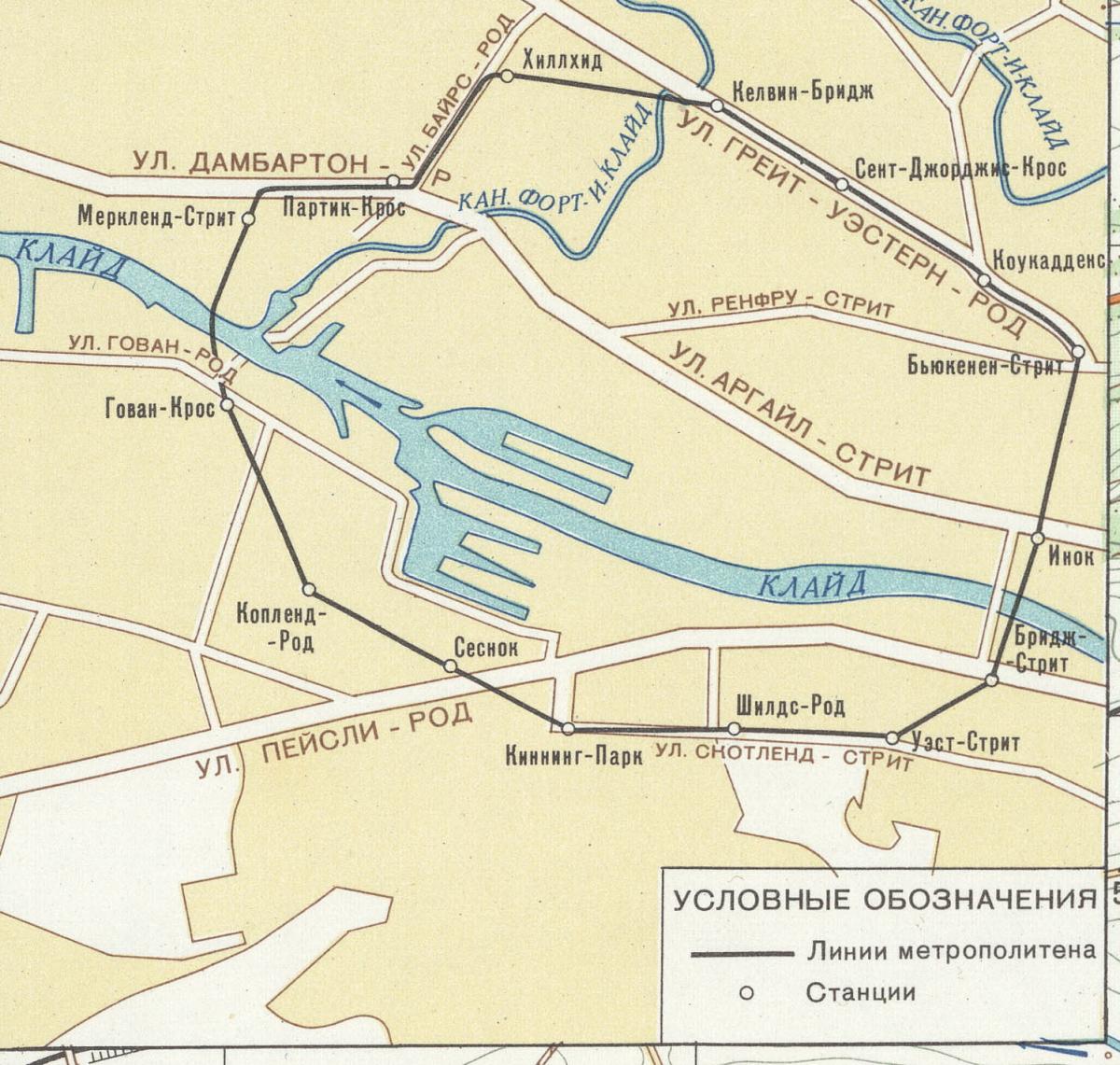

THE maps of Glasgow and Edinburgh may look familiar to people who live in the cities, but the lettering - in the Cyrillic alphabet of the Russian language - will be less so.

For they were among a huge number of detailed maps drawn up by anonymous Russian cartographers during the Cold War.

The once-classified maps do not seem to have been intended to assist a Russian military invasion of Britain.

But it has been speculated they may have been designed to help civilian commanders to run cities in the event of the global triumph of Communism.

The 1:25,000 map of Glasgow and Paisley, compiled in 1975 and printed six years later, shows St Enoch railway station, which was closed in 1966. The 1:10,000 Edinburgh map, compiled in 1980 and printed in 1983, shows the Castle, though it is not listed as a military object.

The maps are in a recently published book, The Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World.

In a foreword, the US author and journalist James Risen says the maps, which span the earth from Miami to Oxford and Helsinki, are “an eerie reminder of an obvious, yet still unsettling fact, at least for British and American readers. They show that the Russians were watching America and Britain, just as much as the Americans and British were watching them. They were looking down from above, and looking from the street. The Russians didn’t miss much.”

John Davies, one of the book’s co-authors, told the Herald that the project began when he chanced upon the maps in a shop in Riga, Latvia. “They had been stored in depots around the Soviet Union so that a military commander could easily get one. One of the top-secret depots was in Latvia. But the collapse of the Soviet Union was so sudden that Latvia, at very short notice, found itself independent.

“The Latvian maps were initially sold as waste paper, to avoid having to carry them back to Moscow, but the smart guy who runs the map shop bought them as waste paper and started selling them. I realised there was something really special here and began collecting and researching them.”

He added: “This Soviet mapping process lasted a good 50 years. The maps are really accurate, and they must have been so expensive to put together. They’re not invasion maps. They’re not aggressive, they don’t show targets or landing-places. They tend to show more civilian facilities, such as bus stations, hospitals and police stations.

“It’s speculation, of course, but the way I have made sense of it is to say, the Communist way of thinking would be that eventually Communism will prevail, as the natural order of things. And when it does, the Soviet Union is going to be in charge of the world. If you’re running these cities [in the book] you’ll need to know what’s there. They look to me like what a civilian commander would need for running a city.”

Mr Davies also has Soviet maps of Aberdeen, Dunfermline and Kilmarnock. “That last one is from the 1960s, but you wouldn’t describe Kilmarnock as a hugely strategically important place. Or Dunfermline either, for that matter. That map excludes the Rosyth dockyard.

“The maps all come from Ordnance Survey maps but the information on them comes from many other sources, including aerial surveillance and trade directories.

“The Glasgow map is interesting because it shows not only the Erskine Bridge but also the Erskine ferry. The two never existed at the same time, but the Soviet cartographers, being very thorough, decided to include both.

“The Ordnance Survey maps used to redact security or sensitive details. The OS map of the time didn’t show Saughton prison, in Edinburgh, but the Soviet map does show the buildings, and lists them in the index as a prison. That’s a common phenomenon in these maps: whereas the OS maps wouldn’t show dockyards or airfields, but the Soviet maps always show them.”

Each map also came with an essay of between 2,000 and 3,000 words describing each town or city in detail, from topography to road networks and ethnicity of the population.

** The Red Atlas, by John Davies and Alexander J Kent, University of Chicago Press, £26.50

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel