THEY called it a “revenant burial”. The grave was dug on the shoreline at Torryburn in Fife and the woman to be buried was called Lilias Adie. Before her death, Lilias had been accused of casting spells and consorting with the Devil and her neighbours feared she would rise again and that her animated corpse – or “revenant” – would terrorise the village. They believed the only way to stop it happening was to place a huge slab of sandstone over the grave, and so, in faith and fear, that is what they did.

Three hundred years later, you can still see that great slab of stone. It’s on the mud flats at Torryburn, not far from the edge of the sea. The remains of Lilias herself have long gone – the grave was robbed in the 19th century – but her life and death still has great power. Indeed, her story, and the stories of other women (and men) like her, have become central to a modern mission: a campaign to tell the truth about the thousands of people accused of being witches and to seek some sort of amends for them.

The campaign has been gathering pace in the last few days. You may have seen the Fife poet Lou Pennie’s tribute online to the women who were murdered or tortured as witches (“we’ll scrieve your name in books they cannae burn”). You may have heard of the Witches of Scotland campaign or listened to one of their podcasts. And you may have noticed the petition that went live on the Scottish Parliament’s website last week. As well as asking for pardons and apologies, the petition also calls for the creation of a national monument, a focal point for the memories of thousands of people who were accused and convicted of being witches.

The driving force behind the petition is the lawyer Claire Mitchell who co-presents the Witches of Scotland podcast with the writer Zoe Venditozzi. Ms Mitchell says her aim is to restore the people caught up in accusations of witchcraft to their rightful place in history as women and men rather than witches. She also believes that, even now, hundreds of years later, some of the prejudices and fears around witches still linger.

The historian Mary Beard would agree with her. Writing in the Radio Times this week, the academic and broadcaster said she is frequently branded a witch online and believes it’s because we still harbour some ancient anxieties about older women. “In the ancient Greek and Roman world,” she said, “they worried that old women were sexual predators. We’ve inherited many of their anxieties and these still fuel the insults that some men throw at women today.”

Douglas Speirs, an archaeologist with Fife Council who rediscovered the site of Lilias Adie’s grave, also believes we still haven’t got our attitudes to witches right. Speaking on the Witches of Scotland podcast, he said society now pretty much sees witches as Halloween figures of fun, but that isn’t the right approach. “Just as society has come round to the proper way of thinking about misogyny and sexism and homophobia,” he said, “we’re still lagging far behind when it comes to witchcraft. These weren’t witches, these were victims.”

The story of Lilias Adie is a good example, although the details of who she was are a little scant (the bits and pieces we do have are from the minutes taken of the accusations against her). She was probably in her 70s. She may have been 6ft tall, which was extremely rare for a woman in the 17th century. She also appears to have had few friends and family and, when she was accused of witchcraft, she was in failing health. The accusation was that she had cast spells to make women in her village fall ill.

The sentence for such a crime in 17th century Scotland was death, usually strangulation and burning at the stake, and we can imagine the confusion and fear Lilias felt at the end of her life. Fortunately for her in a way, she died in prison in 1704 before she could be tried and sentenced to death – as she surely would have been – and, having researched her life and death, Douglas Speirs is in no doubt about how it all ended for Lilias. She was isolated and scared, he says; a vulnerable old woman who was maltreated and tortured to death.

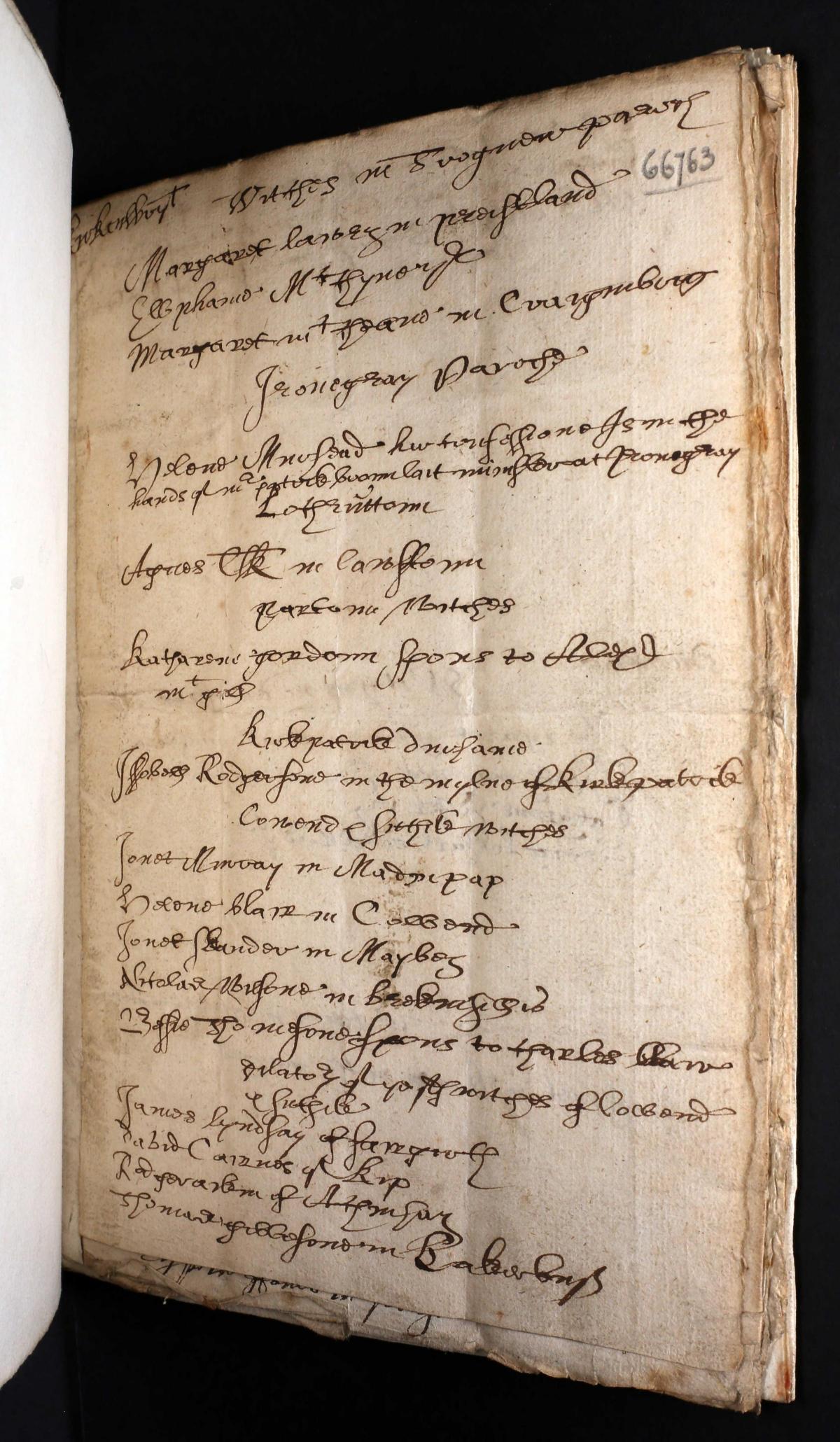

Sadly, there were many thousands more like Lilias and the majority of the victims were women from the lower ranks of society. The first witch hunt was initiated in 1590 by King James VI who had an intense interest in the subject and sent for one or two of the women reported to be witches so he could speak to them personally. One of them, Agnes Simpson, was supposed to have repeated to the King things he’d whispered to the Queen on their wedding night; they were subjects which James swore all the devils in hell could not have discovered.

The result of James’s paranoia and the concerns of the Scottish elite at the time, which filtered down through society, was several periods of hysteria and persecution, although by no means everyone believed it. Among magistrates, there was a good deal of ambivalence about witchcraft and the acquittal rate among witches tried at the High Court in the late 17th century was over 50 per cent.

However, acquittal was not necessarily the end of the story – at Pittenweem in 1705, a woman was stoned to death after being released by the Justiciary Court in Edinburgh. As for those who were judged guilty by the courts, there was only one result: death by violence. The last execution in Scotland was at Dornoch in 1727 when an old woman, Janet Horne, was strangled for allegedly turning her daughter into a pony. The makar Edwin Morgan was inspired by the story to write a poem: “century of enlightenment,” he wrote, “still thirled to torment, thumbscrews and judgment”.

The aim of the Witches of Scotland campaign is to tell Janet’s story, and the stories of people like her who were accused or prosecuted or executed. Claire Mitchell says that between 1563 and 1736, when the Witchcraft Law was finally repealed, there were four distinct periods of so-called satanic panic resulting in almost 4,000 people being accused of being witches. The vast majority – around 85% of them – were women and of the 4,000 who were accused, some 2,500 were executed.

Mitchell and her supporters hope that one day there will be a national memorial to those people. She is also asking for pardons and apologies as not everyone who was accused of withcraft was convicted. But the other aim is to put the history of witchcraft into its proper context. Persecution and panic happened then and, in different ways, persecution and panic happens now.

Douglas Speirs, the archaeologist who uncovered Lilias Adie’s grave, puts it this way: he is not pointing fingers at anyone, he says. The people who accused Janet and Lilias and all the others were shaped by society and condition by their times and the same is true of us now; we are adamant we know what’s right just as they were adamant they knew what was right in the 17th century. The trick is to learn the lessons of those times; to reflect on them, and learn, and change, and apologise.

For more information about the campaign, visit witchesofscotland.com. The petition is at www.parliament.scot

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel