AFTER 18 years, the answer arrived in an innocuous brown envelope.

Helen Harkins opened the letter expecting to see details of a hospital appointment.

Instead there was a paragraph of text saying the very latest genetic research had diagnosed her son Lewis.

Mrs Harkins says: “I had to read it and read it and read it. It was just totally out of the blue.

“I photographed it and I sent the pictures to my husband Brian and he phoned and it was very emotional.”

Read more: Unhealthy food ads targeted in obesity crackdown

“We could hardly talk,” her husband, Brian Harkins, recalls. “We were very choked up.”

They quickly turned to the internet to find out more about what the letter described as “a mutation in a gene called KCNQ2”.

For the first time since Lewis was born, they could research his condition.

However, there was not a wealth of information. KCNQ2 is involved in the proper operation of potassium channels in the brain and mutations are a rare and recently identified problem.

One website would later tell them just 257 children had been diagnosed with the disorder in the world, and just seven in the UK.

Read more: Scottish projects at forefront of latest cancer research funding

Nevertheless Mrs Harkins, 44, felt an overwhelming sense of relief. “It put closure on so many things,” she says. “Why did it happen? How did it happen? It would have made such a difference to our lives if we had known that earlier.”

The couple, from Inverkip, near Greenock, knew something was wrong when Lewis was just three days old. He suffered a seizure in the maternity hospital, his eyes fixed, his body rigid. He spent the next three weeks in a special care baby unit and received medication through a syringe to control the seizures. Back home, aged four months, he was weaned off the drugs and the seizures never recurred. But as doctors monitored his development Lewis, the Harkins’s first child, did not tick off typical infant milestones. His muscle tone was floppy, he could not speak, he did not walk until he was five years old.

“It was horrible,” says Mrs Harkins, a nurse. “It was upsetting and it was very frustrating because you wanted an answer and no-one was able to give you an answer,” says Mrs Harkins, a nurse.

Read more: Buckfast Day celebrations 'bizarre' says former MSP who led failed crackdown

The couple waited until Lewis was seven before they decided to expand their family, unsure if the condition could recur. But not wanting fear to rule their lives, they had Blair, now 11, and Rebecca, nine, who were both perfectly healthy.

Today these younger siblings talk about throwing balls for Lewis to catch and squeeze, and point out where a trampoline is to be inserted in the decking for their big brother.

Inside Lewis grins broadly, claps his hands and springs lightly up and down on the sofa. He is relaxed and happy in a home flowing freely with family and friends. He is also enjoying the cream couch, given he is usually directed to the firmer brown one bought to withstand his inclination for bouncing.

But aged 18, Lewis cannot talk. If he is in pain, his parents say he cries and bites his hand but cannot point to suggest what is wrong.

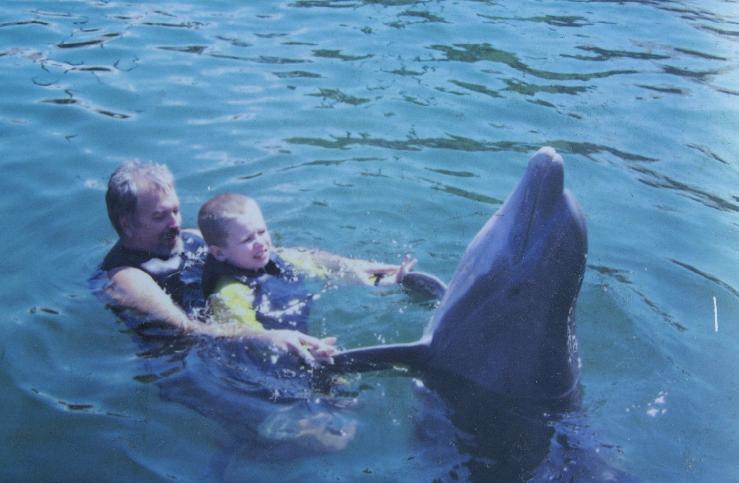

Over the years they have investigated many possibilities to explain and improve Lewis’s condition. They regularly visit a specialist centre for brain-injured children in England. Lewis has undergone oxygen therapy and been to Florida to swim with dolphins – each adventure making small differences.

He has begun to make more eye contact and now loves social gatherings.

Mr Harkins, 42, says at the beginning one consultant told them to stop wasting their money and to accept their situation.

They ignored him. When Lewis was five they paid to see a private paediatrician who led them to seek genetic testing to identify his condition.

Routine blood tests revealed nothing, leaving the family only with speculation – it might be cerebral palsy, it might be autism.

Then in 2011 they received a letter inviting Lewis to participate in a Deciphering Developmental Disorders study. They posted off a swab taken from inside Lewis’s mouth and that is what, five years on, led to the surprise letter from the Department of Clinical Genetics at Glasgow’s new Queen Elizabeth University Hospital.

Within days they were talking on the phone to a father in Dublin whose toddler has the same KCNQ2 mutation.

Mr Harkins, a financial adviser, says: “All of a sudden we were talking to someone who knew exactly what we were going through, but he was even more delighted because of Lewis’s age. Because of his kid’s complications he was thinking about the possibility of short life expectancy.”

Knowing what has affected Lewis has given the Harkins family hope – treatments are being researched in America – and while they recognise genetic testing can be an arduous process that is not readily available on the NHS, they want other families to know the possibilities it might offer for them.

Mrs Harkins says: “We know a lot of children that are like Lewis and have never had a diagnosis so you can bet that there will be children with the same problem. I would like people to know that they could get a diagnosis.

It might not be that the child has this gene, but it is another route for them to explore.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel