PHILL Jones arrived at the Faslane Peace Camp in the same month as Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s anti-nuclear anthem Two Tribes went to number one in the British charts.

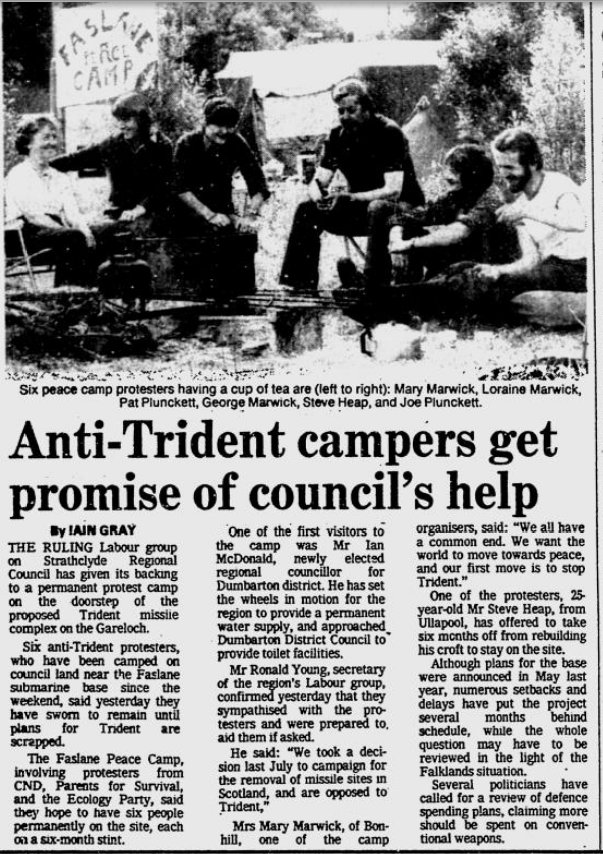

Gallery above: early protesters at the camp in 1982.

The camp had been going two years by then. Margaret Thatcher was in Downing Street, Ronald Reagan was in the White House, the Soviet Union was still in existence and fears of nuclear destruction were the stuff of Hollywood movies and BBC drama.

He spent the next nine years on the camp. In that time he rammed a Trident submarine, became a father and even broke into the control room of a fully armed Polaris submarine. "Margaret Thatcher was furious I wasn’t shot, according to Bernard Ingham."

Mr Jones was one of the original generation of peace protesters. As the camp turns 30 a new generation are trying to revive its fortunes.

Leonna O’Neill is one. Ms O’Neill, 27, and originally from Belfast, has been living in Faslane for the last 18 months.

She’s one of six permanent residents at the site who have been working to improve its visibility. "We’ve worked really hard to clean the place up and get it functioning again and get more actions happening," she says.

This month the peace protesters are carrying out "30 days of action" to mark the anniversary.

Leonna O’Neill and protesters at the camp this week (Photo: Colin Mearns)

It's the latest chapter in the camp’s 30-year history. In the eighties there were more than 20 people living permanently on the site but the removal of a site licence in the late nineties saw the camp shrink in size. There are more general reasons too.

Ms O’Neill admits the issue of nuclear weapons is much less visible than it was in Mr Jones’s days. "Nuclear weapons have been normalised and they’re no longer shocking," she says.

More than that, she says, "the anti-nuclear movement has failed to attract a younger generation basically."

But the fact that the peace camp is still there is something to celebrate, believes Mr Jones. "At the end of the Cold War the peace movement in England pretty much collapsed. The peace movement in Scotland remained quite robust and the peace camp was at the forefront of keeping the whole nuclear issue alive."

And for Mr Jones and many others, Faslane remains a symbol of the fact that for some weapons of mass destruction are unacceptable. "It’s a permanent reminder to people who pass by that there is huge opposition to weapons of mass destruction," points out Jane Tallents, who lived on the camp in the eighties.

Ms Tallents, 54, Mr Jones’s former partner, now lives in Helensburgh. She still pops into the camp every Wednesday, "so that people see that some of us opposed to nuclear weapons have nose rings and wear black and others are pensioners and wear ordinary clothes."

In her time at the camp she helped organise direct action, was arrested more than 40 times. "It’s an occupational hazard of being a peace protester".

Ms O’Neill believes that independence – and the Scottish Government’s promise of the removal of Trident – might offer new hope to the anti-nuclear movement.

"Obviously I’m quite cynical about politicians and their promises but I hope it will open the debate at the very least."

"I think an independent nuclear free Scotland is the only kind of hope that I can see," Ms Tallents agreed. And if Scotland were to become Trident-free, she said, there wouldn’t be any need for a peace camp any more.

"I admire all the years and years of commitment that people have put in to keep it there but I want it closed. I look forward to the day when that camp can become a peace garden."

From the archive

The Glasgow Herald covered the story of the camp from its earliest days.

Below are the first articles that appeared in the newspaper.

The Glasgow Herald, 16.6.1982

The Glasgow Herald, 04.4.1983

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article