LIKE most bookworms, if I had the choice I’d spend all day, every day, closeted away with a novel. I’m at my most content when sunk in a fictional environment, whether it be a slapstick 1950s university campus, a dystopian near-future, a high-stakes game of Cold War espionage, or the court of some venomous monarch where everyone dresses in tabards and hose and flamboyant hats and murders their siblings. I chain-read, sparking up one book after the next. I fret about the good stuff I’ll probably never get round to and lament that we don’t have two lives: one to live and one to read.

There are periods when this flight into imagination becomes more than usually essential to mental hygiene – now, for example, in the time of Brexit, Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Jeremy Corbyn and the rest. In fiction, the baddies usually get their comeuppance, and often a smack on the jaw for good measure. In real life, they win elections and referendums and poison people and cultures. Literature can be cathartic.

In my experience, the most avid consumers of quality novels tend to be liberal in their politics, and I don’t think that’s any coincidence. I think of books as weapons of mass construction: they build empathy, tolerance and perspective within the reader. On one’s reluctant return to corporeal existence, those who hug the ugly extremes appear ever stranger and under-developed, as if an important piece of them is missing. It is hard to take conspiracy theories and theorists seriously. It is natural to understand and sometimes sympathise with differing but reasonable points of view. Doubt is healthy. Certainty is for fools. Such, the reader knows, is the world.

The most perceptive and, for me, rewarding speech by a politician so far this year was given earlier this month in Edinburgh. Nicola Sturgeon didn’t talk about the dangers of leaving the EU, or the challenges facing liberal capitalism, or the future of the independence movement. She talked about books. It was a speech that few other members of our ruling caste would or could have delivered. It, and the message it contained, would have benefited from a much larger audience.

Ms Sturgeon is nuts about books. She likes to chat about them, to swap recommendations, to critique the ones she has read. She has a teetering to-be-read pile. When I interviewed her for the New Statesman last September, she raved about Bernard MacLaverty’s Midwinter Break and had just finished Paul Auster’s 880-page 4 3 2 1 (“It was OK. I don’t think it should be on the Booker shortlist.”) The most common response I received to the subsequent article was ‘how on earth does she find the time to read so much?’

She is probably the most literary British leader since Harold Macmillan, who could often be found in a dusty corner of Number 10 buried in a volume of his beloved Trollope. Macmillan had a head start – his grandfather founded the publishing imprint that bears the family name. Ms Sturgeon has nurtured her habit from an ordinary childhood in Ayrshire to the noble, echoing spaces of Bute House.

The First Minister’s speech was to a gathering of young people working in the publishing industry. She described books as “with no word of exaggeration, my favourite things in the world. Reading is one of the great joys of my life”. She recalled her fifth birthday party: “I remember hiding under the kitchen table, reading a book, while all the other kids were playing Ring a Ring a Roses. In the years since, I’d like to think I’ve become a bit more sociable – though if I’m being totally honest, hiding under a table reading a book is probably still what I’d choose to do most days if I was able to.’

What a wonderful thing for a First Minister to say – what a great message to send about the importance of a rich inner life. Our modern environment places such emphasis on high academic achievement, on career advancement, on earning money and pushing oneself to and even beyond the max, that falling short in these areas is portrayed as failure. We all know kids who have been left thinking they have no future due to unexpectedly poor exam results; or colleagues who have sunk into depression when the coveted promotion or pay rise goes to someone else. We’ve too often come to measure ourselves through external validation.

Ms Sturgeon’s point is that while public success is an important aspect of who we are, it’s not everything. And she should know. “Reading is such an essential part of my being, I can’t imagine life without it,” she told her audience. Without explicitly saying so, the implication was clear: she could imagine life without politics, without power, without Bute House. Of course she could. But not without books.

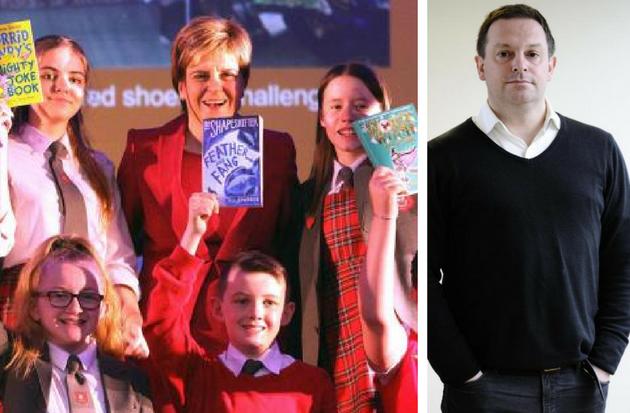

Working with the Scottish Book Trust, she has launched the First Minister’s Reading Challenge for children in primaries 1-7. It’s a modest but lovely effort to help build and sustain a reading culture within the classroom, on the basis that “reading has the power to change lives, and developing a love of reading in childhood can have a huge impact on educational attainment and future wellbeing”.

Under the scheme, schools can order Reading Passports that pupils use to log the books they’ve consumed. There are learning resources, reading suggestions, tasks and ideas, and small grants are available to cover new books and author visits. A range of prizes will be awarded in June this year.

Ms Sturgeon reads “for pleasure” and to gain wider experience of the world, ideas, and people. “At their best, books can give us a new perspectives and insight into the human condition – expanding the empathy we feel for people in different walks of life. Reading also helps me reflect on and gain perspective on my own life and priorities,” she says.

The First Minister and I will always disagree about plenty, but on this we are in perfect accord. Tending to the soul should be the kind of national cause that unites us all.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel