THE young, in England, according to a new report by the Office Of National Statistics, are three times as likely to be lonely as the old. Each time I read figures like this, I’m shocked, though the past few years have brought us study after study telling this story. Earlier this year, The Mental Health Foundation, revealed that more than half of young Scots between the age of 18 and 24 said their mental health was impacted by loneliness.

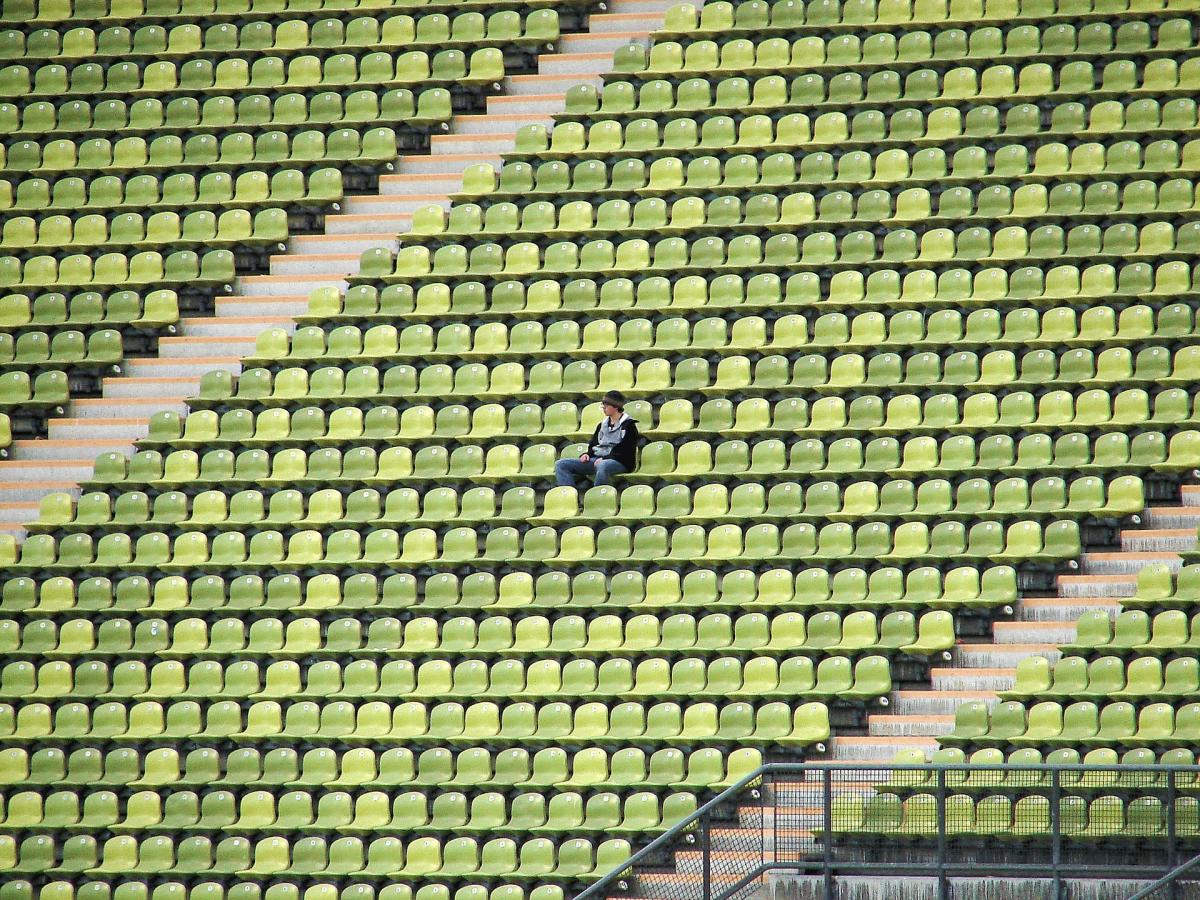

We tend to think of loneliness as the preserve of the old. That the young, with all their dynamism, are suffering and alone, seems not just shocking, but also tragic, as if it were a waste of youth.

Whenever statistics like these are published, there’s a rush to explain the problem. Normally the first culprit we point to is social media, and the way our lives are now lived through screens, rather than face to face. I agree, this is a key element. But social media doesn’t work alone. Wider trends in our increasingly competitive, fragmented society are also atomising us.

Social media, for instance, has exacerbated a growing tribalism. The American social scientist Brene Brown, has noted that, in the United States, people are now more “sorted” than ever into groups with similar worldviews. The same, I believe, is the case here. The people with whom we work, live and spend leisure time, are increasingly likely to share our values.

Social media has allowed us to “sort” still further, find these like-minded others and feel we are part of something. It’s seductive and thrilling. But it can also be empty. For, membership of these groups doesn’t revolve around acceptance of who we are, but, rather, a liking for shared ideas. Were we to change our ideas, we would no longer belong. We would be, once more, alone. And, in our terrifying social media climate, harangued by the people to whom we once felt connection.

What we have lost Brene Brown says, is a belief that we humans are “inextricably connected”. To find that again what we need to do is cultivate is "real connection and real empathy” ¬ and we only get those by meeting real people in a real space.

Preferably, I would say, we need to do that in the places in which we live. Belonging and connectedness, after all, can’t float out there on a digital cloud. They have to start with involvement in groups and activities within a stone’s throw of your home.

It’s not hard to see why such belonging isn’t so available to Millennials. For a start, they are “generation rent”, less likely to own their own homes, and,as the ONS report points out, homeownership is linked to less loneliness. Their belonging is rendered more fragile by the fact that their landlord might turf them out. That’s not just so for Millennials. It’s so for all whose tenure of their home feels insecure, particularly for the homeless.

Work, also one of the places where people find belonging, has been fragmented too, through zero-hours contracts, home-working, and the waning of the unions.

How do we stop all this? Millennials, of course, are finding their own answers. But it’s up to all of us to stop this loneliness tanker. Partly we can do this by finding any and every excuse to physically come together. We can do it by teaching children that those who pursue stardom are just as likely to be lonely as popular. We can do it by pushing for a housing system that’s about what people and communities need, rather than profit and investment. Above all, we can do it, by reminding each other that we are in it together. This is not just one person’s problem, it’s everybody’s.

NOT sure why exactly, but I’ve known a lot of girls who have had a bit of a thing for Spiderman merchandise and clothing. Well, who wouldn’t ogle a nice Spidey t-shirt or pair of trainers, and not think they were born to wear them? So, it’s hardly surprising to learn that, in the United States last week, one two- year-old girl was very upset to find that Target only stocked Spiderman trainers for boys, like her brother, and not for girls like her. Subsequently her dad complained to the store over social media, triggering wider outrage.

On one level, I don’t see why the girl couldn’t just have those trainers – in fact she did wear her brothers’ in the end. I’m sure if it were my daughter I’d have just been buying the shoes and sending her off to climb a few walls with them. I was also baffled by the fact the dad complained that Target “don’t sell Spider-Man shoes that fit 2 year old girls”, when girls and boys feet are the same. But never mind, the Twitter complaint definitely drew attention to the issue of the gender silos that children’s clothes are marketed in. That dad had an activist's flair.

But also what struck me was that, actually, a girl wearing some Spidey gear is really on the soft end of gender code-breaking in children’s apparel. Most parents wouldn’t blink an eye at buying such trainers, or at other girls wearing them. What would be far more revolutionary, and trigger many more objections of political correctness, would be a boy wanting a pair of pink sparkly Barbie trainers.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel