LIKE many daughters, Gail Pirie was and is immensely proud of her father. “My hero,” she calls him now and called him then. Yet for many years she never revealed his identity to strangers because she was afraid of what might be said.

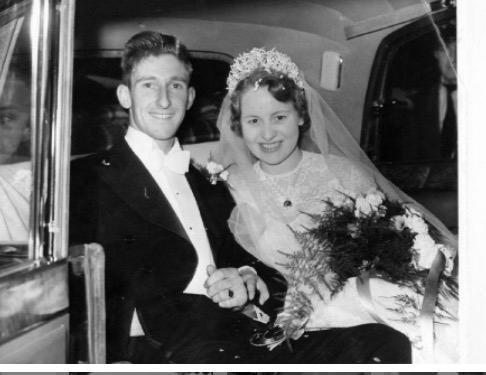

Her dad was a lovely, family man, a patriarch who almost always had a smile on his face. He provided a good life for his flock and yet, and this is using Gail’s words, it was only when her dad’s name was outed at work that she would talk openly about him.

“You should be proud,” most but not all declared. And she was. But some would bad-mouth this gentle man and gentleman to her face. It began in 1978 when she was 14 and it continues even to this day, some eleven years after his death.

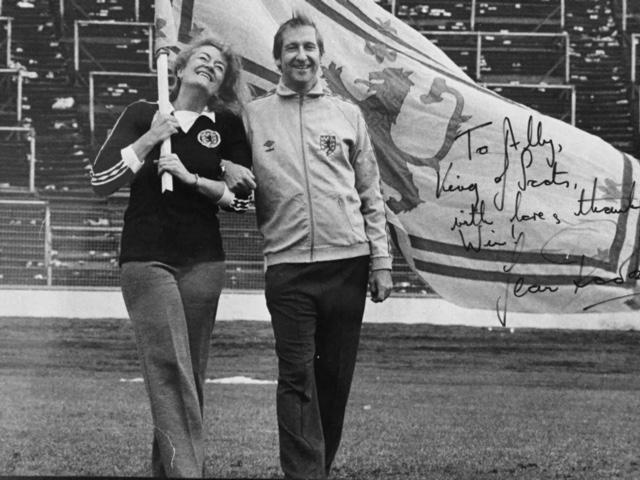

However, Gail is now “a woman possessed” as she spends lots of time on social media, making calls, sending emails and putting out the word about her father, one Alistair ‘Ally’ MacLeod, former Scotland manager and one-time hero of the country who became public enemy No1 because the national side failed to win the World Cup in Argentina.

She is on a mission to get Ally into Scottish Football's Hampden Hall of Fame, which in her mind would give the man some better-late-than-never recognition for what he contributed to football in this country, and also for making us Scots feel good about ourselves for about a year or so when we were going over to the Argentine to beat them all.

As the man himself memorably said when asked what he would do after the World Cup, he said: “Retain it.” You’ve got to love that.

MacLeod has been nominated many times since 2004, when the Hall of Fame began, but has never been put forward as one of the inductees, which will surprise many and certainly infuriates the family who claim there has been bias against him by some members.

Now I will declare an interest here. For many years, although not since 2009, I was a member of that panel and hand on heart I can’t remember the subject of Ally McLeod coming up at the voting lunch, although his name must have been put forward. I was, however, genuinely stunned to discover one of seven men who have taken Scotland to any major finals has been snubbed.

“Dad energised the country in 1978,” Gail, someone impossible not to like, tells me. “We don’t want him recognised for that two-year period when he was in charge of Scotland, but for the 50-plus years of service given to Scottish football. It was two bad games for goodness sake.

“He has never been inducted into the Hall of Fame and it’s something I am bitter about. I am told certain members of the panel are dead against it and one even claimed that as long as he was a part of it them Ally wasn’t going in. I think that’s dreadful.”

I must admit that this is a difficult to accept given I know many members on the panel, however, the family believe a whispering campaign against MacLeod has tarnished his name.

The extended family are not about to let this lie. Ally died on February 1, 2004 as a result of Alzheimer’s at the age of 72. He had battled the best part of the last decade of his life with this horrible disease.

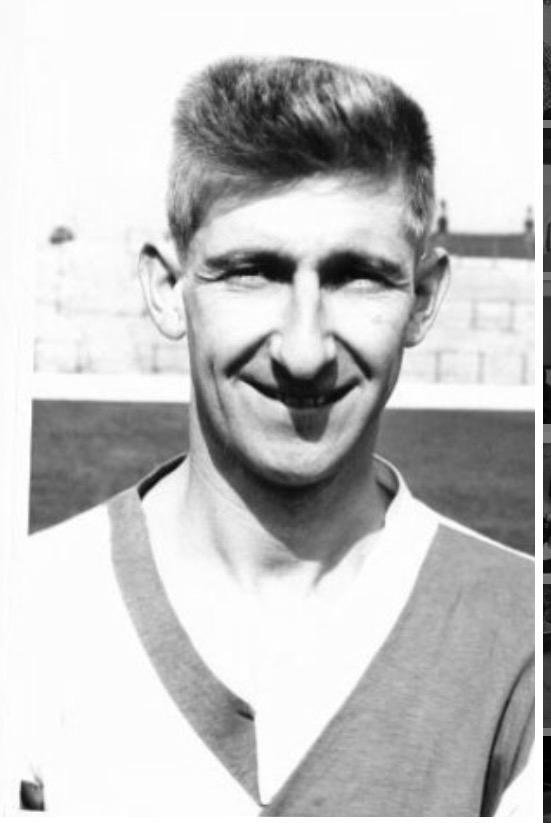

But this is not why they want him recognised. Rather, for what he achieved as a player with five clubs which including two spells at Third Lanark, Hibernian and at Blackburn Rovers where he played most of his football.

And as a manager. He was successful at Ayr United and Aberdeen. He also had spells in charge of Motherwell, Airdrie and last of all Queen of the South. He left there in 1992 and that was that for MacLeod and football.

With Scotland, and, yes, Argentina was a disaster, but he did win the 1977 British Championship including a famous Wembley victory. Only Willie Ormond, whose team went out of the previous World Cup in Germany without losing a match, can boast a superior record. MacLeod saw his beleaguered squad lose one, draw one and then lastly they beat the Netherlands, who would go on to compete with the home nation in the final itself.

Jock Stein has exactly the same record, which is more than can be said for Sir Alex Ferguson, who didn’t win a game in Mexico, or Andy Roxburgh or Craig Brown.

“Ally did no worse than any of the rest,” says Gail who often calls her dad by his first name. “And yet he was crucified by the country as if it was his entire fault. It was an awful time for the family and one we remember well. I found out who my friends were. They all wanted to know us and then they turned their backs. This was 1978 and I haven’t spoken to a lot of people since.

“For years I didn’t want to say who my dad was. Isn’t that awful. I just never knew was someone’s reaction would be. I’ve worked in Crosshouse Hospital for 21 years now and for a long time I didn’t mention him.

“During the World Cup, me and my two brothers lived with mum and dad in a tiny cul-de-sac in Ayr, just four houses, and we couldn’t get outside because of the press. We couldn’t get to school some days. My wee granny would come and open the door to reporters because after a while my mum couldn’t face it.”

This all could have been avoided. Jock Stein told his friend to wait a few years because the World Cup was in South America and he was onto a loser no matter what – and anything that could go wrong did so to the nth degree.

“We lived in Aberdeen and had a great 18 months up there,” Gail recalls. “Dad had done well (he had won the 1976 League Cup) and was settled. But felt he couldn’t say no to what he called the biggest job in the country. Years later, when we would ask him, he said that there was just no way he could turn it down.

“Yes, he was the manager, but at the time it was as if he was the only to blame. The big send off at Hampden, that was nothing to do with him, that was all Ernie Walker, and for years people were so cruel about him.”

From profit to pariah because of some football results. Time gives us all clarity and it is perhaps not this industry’s greatest moment that all the ire turned one one man, and a decent one at that.

“Dad was a lovely man, very kind.” she says. “He could be quick-tempered and also quite intolerant, but he loved a laugh and a joke. He was always smiling. He was also a man’s man. No matter where he was he had to hold court. He was happiest talking football and telling people stories about his life.

“The World Cup broke him. Yeah, he was a broken man when he came back. We saw it, but the public didn’t. He always put on a smile but that wasn’t him. Not for a long time.”

The real tragedy is not the Hall of Fame or even Argentina, but that just when MacLeod was content with his life, which included many grandchildren, he began to show signs that things were not right, as his daughter recalled with a heavy heart.

“Ally was about in his mid-60’s when he started to forget things. We noticed he was changing and so did he. At the start, he was utterly aware of it. He would get annoyed because he lost his keys and started to write things down so he wouldn’t forget.

“By the time he was diagnosed, he wasn’t aware. Physically he was no different, but mentally he was gone. It was awful to watch and we tried to protect him by not telling anyone, or at least keeping it as quiet as we could.

“Dad would wander off. I would joke with mum that he would end up some cold snotter on the street. He would try to get the bus back to Mount Florida where he came from and once he even made it to Glasgow. Football was his life. He could still remember games from years ago and I knew the stories were true because I knew them. He just couldn’t remember what he had for breakfast.”

The family eventually decided to reveal what was going on to the public, including a very touching documentary about him on the series Footballer’s Lives.

Gail said: “That was one of the last things we did, if not the last. That and a newspaper article were the best things we could do because it alerted a lot of people to what was going on. Men in particular would say that they wondered why Ally had ‘blanked” than in the street when they had said hello. It was because he couldn’t remember them.

“Of his grandkids, only Ryan, who is now 26, can remember him before he got ill. As for the rest, they just knew him as Grandpa who was ill and kept forgetting things. None of them know him for the football.”

The Ally MacLeod Tartan Army and We have a Dream Tartan Army, both from Ayr, are coming together on the October, 8 to walk from Somerset Park, his home from home, to Hampden Park for the Scotland v Poland Euro Qualifier in aid of Alzheimer's Scotland. That’s 34 miles. Nominations, Gail tells me, for the next lot of inductees come out in mid-September so the walk will be too late for that.

“The most important thing is the Hall of Fame. That’s what we want. I am not going to stop pestering people....although you are the first one who has responded.”

Anyone interested in the walk or the man himself should go to www.allymacleod.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article