IT has been accepted that I know as much about tennis as the next man. As long as the next man is an Amazonian Indian whose grasp of anything post the discovery of fire is limited to referring to the 7.10 redeye from Recife to Sao Paolo as the Iron Bird With White Feathers.

My ignorance of tennis is such that much has been made of my inability to pronounce the names of the stars. A certain J. Murray believes that I have changed Milos Raonic’s nationality to Irish by calling him Ray O’Nitch. My tactical analysis is such that on being apprised of my views tennis savvy households adopt the pose once made famous by the extra-terrestrials in the Smash advert. For those of less mature age, suffice to say this involves lying on one’s back, kicking the air and laughing uproariously.

It was with some satisfaction, then, that my tennis nous came in useful on a visit to Wimbledon the other week. Idling by a doubles match, I was intrigued to discover that a fellow spectator had identified one of the players as Andy Murray’s brother. I intervened gently. “No that is Jonny Marray. He is Andy’s English cousin. Hence the spelling.”

Emboldened by this articulation of years of accrued knowledge on the tennis beat, I am going to offer another opinion.

People sometimes fall in love with the image rather than the reality in sport. And they are short-changing themselves, perhaps even missing the authentic nature of the champions they love.

It is most stark in the perception of Roger Federer, who left Wimbers at the semi-final stage at the powerful hands of Mr O’Nitch. Federer is lauded for his talent, his effortless grace and his sportsmanship. Yet all three of these traits must be scrutinised.

Yes, Federer is supremely gifted, but so are many who fail to deliver at Grand Slams. His “effortless grace” is the product of disciplined hard work. And his sportsmanship? Federer does what it takes to win. As he should. But even a cursory glance at his record shows he is not immune to the blowouts that seem more faithfully recorded when they are committed by others.

I have listened to Federer swear at an umpire in a Grand Slam final and swear at an opponent in a Grand Slam semi-final. He was, too, a champion racquet thrower as a junior. He can be narky and less than gracious when beaten, too.

This is not to degrade Federer, but to accept fully what makes him a genuine contender for greatest tennis player of all time. Federer has his individual, extraordinary brilliance but he shares much emotionally with such as John McEnroe or Jimmy Connors. There will be a massive intake of breath at this assertion among the Fed Army. But that does not make it less true.

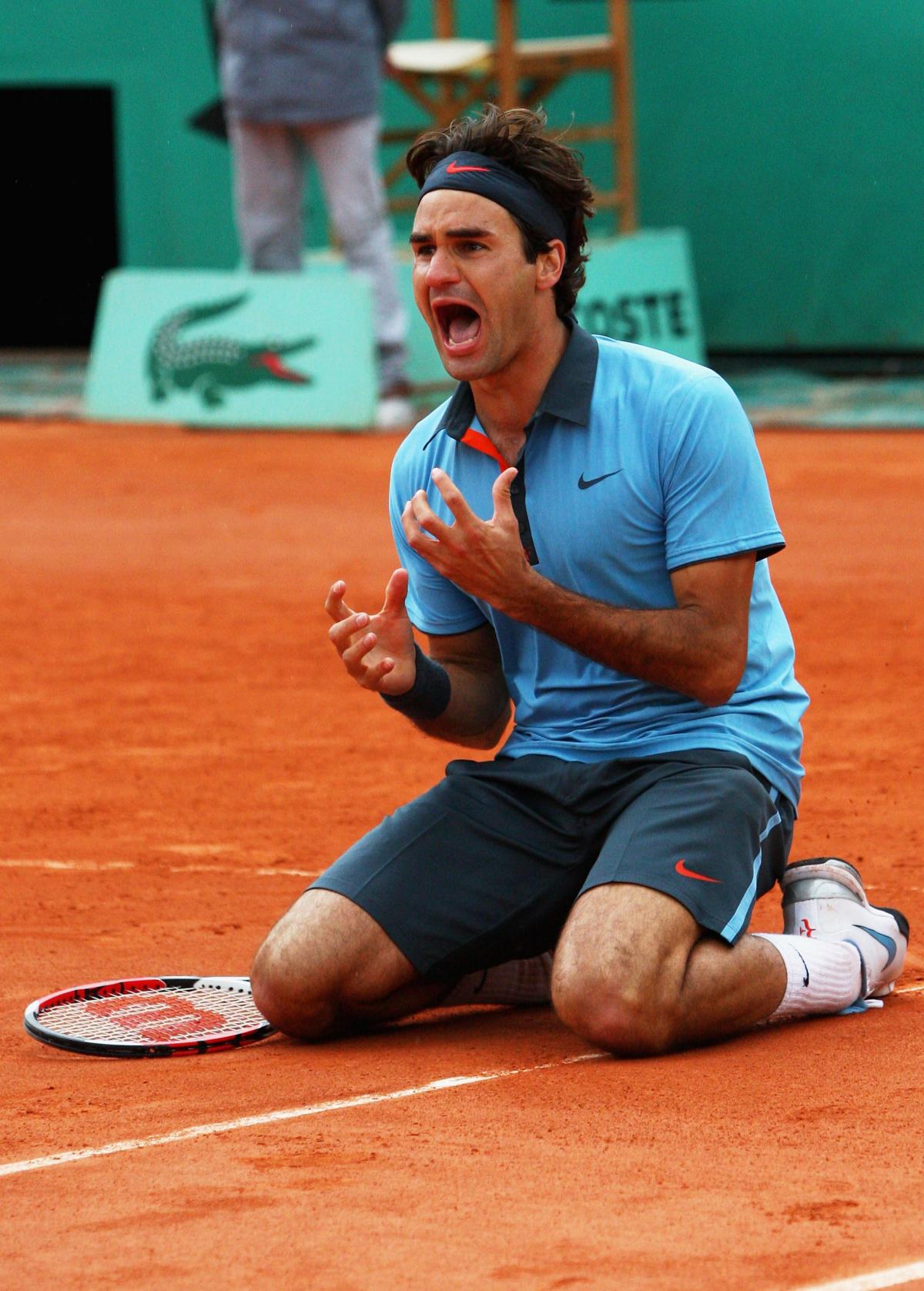

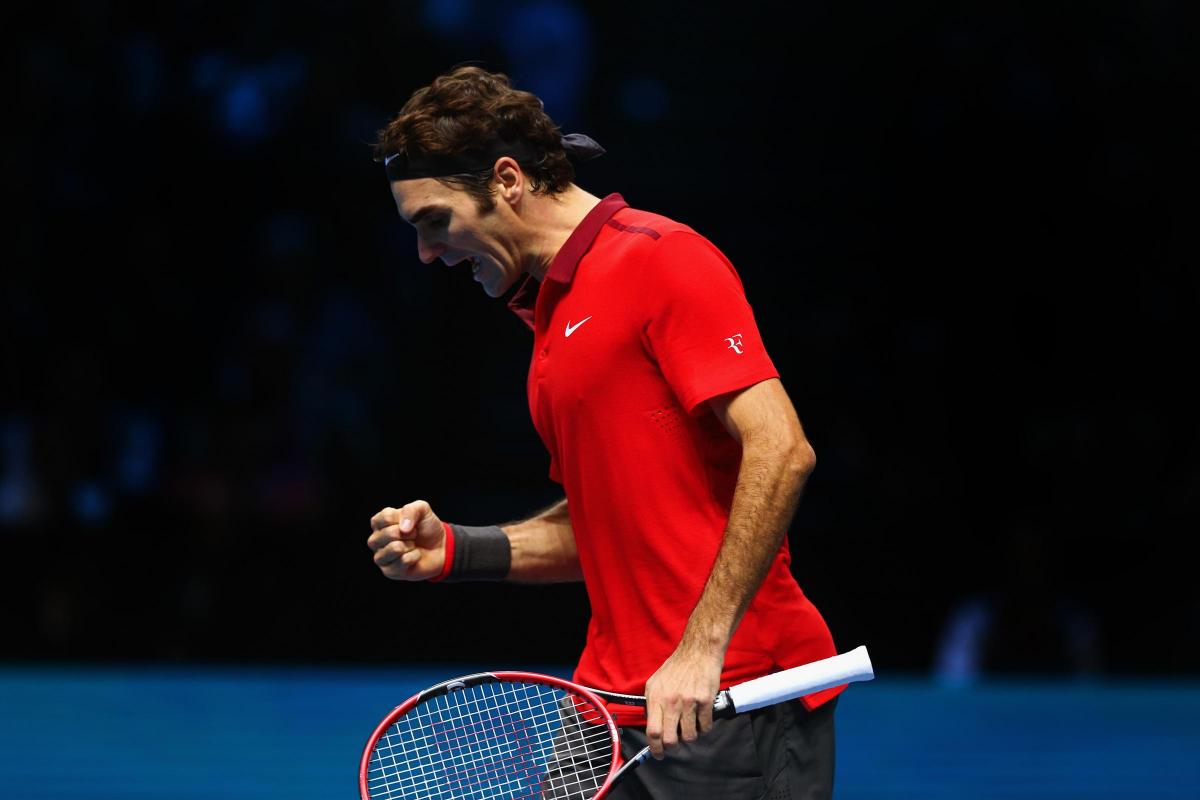

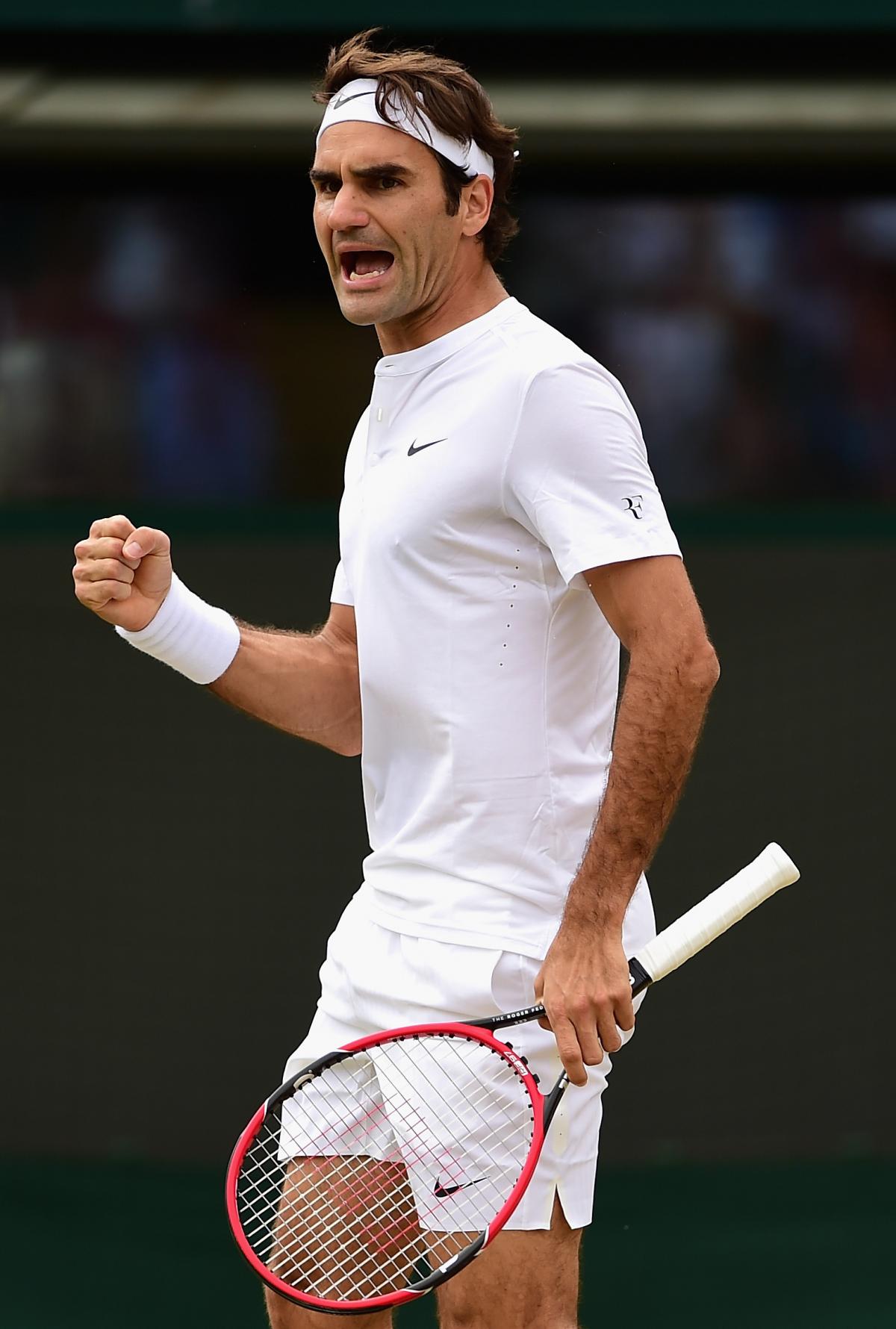

Federer is a winner. The statistics prove that but so does his attitude, his behaviour and his response to challenges from fellow competitors.

The real Federer has been wrapped in a cloying, sentimental sweetness that does him a disservice. He is not some flamboyant cavalier swatting away his attackers with a one-handed backhand. Yes, he has sublime technical skill, never better captured than in that extraordinary David Foster Wallace essay. But all that means nothing if it is not accompanied by a toughness not just of body but of spirit.

His smile is genuine in victory and he is clever, articulate and mostly amiable in press conferences. But Roger Federer is as hard as a diamond left at the back of a fridge in the Siberian tundra. He is unforgiving to opponents. He is relentless on himself. He is ruthless when spotting an opening.

He also carries the true scar of the champion. He has taken the blows and has come back for more. He has shouted, cursed and railed against the fear of sporting mortality. He has clawed his way back from debilitating injury and is snarling inwardly at encroaching age and the limits it places on him.

All this provided him with glory last week but also despair. But the Federer narrative is no fairy tale. It is, instead, an everyday story of how champions take their talent as the starting point and build floor upon floor of achievement upon it. Federer’s sporting edifice now stretches towards the heavens but it is a product of dark, driven forces as well as luminous brilliance.

There is no shame in this. It is the mark of the champion even if the besotted admirer does not want to accept it. Federer has walked the hardest of roads. He has been fuelled by obsession, driven by an innate desire to win.

The hardest day lies ahead, however. Federer will have to stop playing professional tennis. Not now, not next week but sometime. He will need all his mental strength to come to that decision. And then to live with it.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here