The name has a hint of fifties schoolmarm about it, the accent is distinctly North American and the residence is Wimbledon, none of which offers much in the way of clues to her principal sporting interest.

Admittedly her home province is Nova Scotia, while Scots have acquired a new status in the leafy London suburb due to their sporting prowess over the past decade, but even that does not narrow it down much.

Joy Elliott-Bowman - the hyphen is a marital choice rather than reflecting aristocratic background –grew up, of course, with ice hockey, so initially tried field hockey on starting her course at Aberdeen University a decade or so ago but found it too technical. When, then, a classmate suggested she might feel more at home with an alternative which permitted, albeit on grass, use of both sides of the stick, she found an immediate affinity with shinty’s apparent lawlessness, what rules there are largely indiscernible to the ignorant onlooker, while causing relatively little inconvenience to even the most robust competitors.

She consequently became so hooked that when, in 2012, work took her and wife Bernie south, they immediately sought out the small band of brothers and sisters engaged in the good fight, promoting this most Scottish of sports in England’s capital, a battle that has been going on for some time it seems.

Now the out-going captain of the London club, albeit set to lead their first all-women’s team that is currently being set up, Elliott-Bowman offers an illuminating history lesson that dates back to the 19th century and effectively outlines the debt Brian Clough, among many others, would seem to owe shinty.

A stick used by the original Nottingham Forest Football and Bandy Club in 1865 sits among FA Cup medals and an ornamental canon gifted to the club by Arsenal in the boardroom at the City Ground, marking the link (bandy being a version of the sport played on ice) as Elliott-Bowman explained.

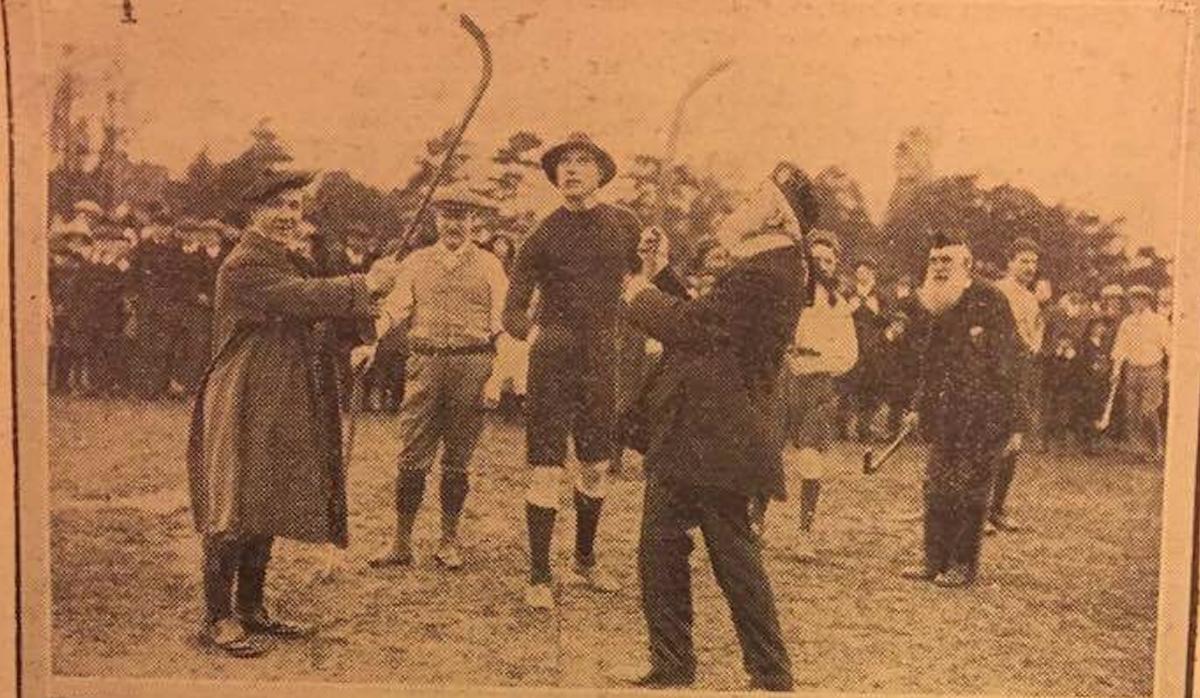

“The London Shinty club dates back to 1894 so there’s been a team of some description, on and off, since then. The Northerners and the London Scots merged at that point.

“The Northerners club was based at Nottingham Forest. That was the start of the football team there. Shinty was there before the football team, then there was a shinty and football club and then they kicked them out. Quite a few of the Northern football teams started as shinty teams,” she reported, with one of the many good-natured chuckles that accompanied her discourse.

So much, then, for any notion that it has been forever confined to Scotland’s Highlands and islands and, indeed, Elliott-Bowman admits that having grown up in what is something of a Canadian Celtic stronghold, she was not unaware of shinty’s existence before she crossed the Atlantic.

However she and Bernie also arrived in London at just the right time because, for all its provenance, the London club had been in abeyance for several years just before they arrived.

“There had been a bit of a hiatus from 2006 to 2011 when there was no team. In 2011 Graham Love, who was the captain before me, had moved down to London for a job in engineering and decided to try to re-start it,” she noted.

“He got in touch with a number of the guys who had been playing in 2006. Some came back and then he started collecting people who had moved down but for the first two years there were maybe four or five of us at training at a push.

“However at the same time there was an interesting revival going on in Cornwall which is a shinty hub in England now. Again it was a University connection, someone from Cornwall who went to St Andrews, got things started. So there was a bit of a rivalry developing there, then about two years in another St Andrews player came to Oxford and started a team there.”

The Cornish club ended a much longer suspension of activity, the best part of a century having elapsed since accounts of previous matches there, but when the scale of activity proved sufficient to justify the creation of an English Shinty Championship, their genuine Celtic heritage perhaps explains why, for all their relative newness, the Cornish team has dominated the English Championship in recent years.

Rivals they may have become, then, but that is set aside when the clubs get the chance to compete internationally, both as the English Shinty Association, competing in the Bullough Cup with clubs from the reserve divisions of Scotland’s South District and in what have been the first ever shinty internationals not involving a Scotland side, when they have taken on a Rest of the World team comprising an unlikely alliance of players from Krasnodar in Russia and California at the St Andrews University shinty festival.

“We have a lot of challenges with funding because it costs so much to play,” Elliott-Bowman admitted.

“Within England our nearest team is Oxford, so it costs a lot to travel around and even when we play the English Championships in Bristol it’s a three hour drive.”

In bidding to make it more accessible they have recently shifted their training, which always takes place at weekends, from Garrett Green in south London, to twin bases at the traditional rugby stronghold of Blackheath in the east and Northfields in the west of the city.

“Then we come together in Clapham Common once a month to play a series of small East versus West games,” said Elliott-Bowman.

“We play there because it’s a very popular common, so we’re hoping people go ‘oh what’s that.’”

That crafty marketing has worked with players, including England’s current goal-keeper who fancied joining in after seeing them play while picnicking with his girlfriend, having been recruited that way, around 20 per cent of their players now comprising those they have initiated in shinty, while some 40 per cent were introduced to it at University and the rest are ex-pat Scots, including Owen Ferguson who played for Lovat when they won the Camanachd Cup in 2015.

The powers of persuasion at play have also been demonstrated in their unlikely award of funding from SportEngland, an organisation that might have been expected to have baulked at being asked to support such a characteristically Scottish sport.

That sits curiously at odds with the attitude of those who run the Royal Parks which might be expected to have a wider remit as centrepieces of the British capital.

“The Royal Parks have a list of sports they allow to play on their pitches and since they hadn’t heard of shinty it isn’t on the list,” Elliott-Bowman pointed out.

“Baseball is allowed to play on the Royal Parks and we’re not. Hurling isn’t allowed either, the Scottish and the Irish, no. We’ve complained a couple of times and shown them the website of the Camanachd Association with the rules and safety regulations and pointed out that we are a bona fide sport.

“They’ve got some really nice rugby pitches and facilities and, of course, it’s central London, so we would love to play our London Festival in Regent’s Park for example.”

All a bit odd, really, given the eagerness with which the London elite expresses its desire to wrap Scots within its all-embracing cloak of Britishness. However much official encouragement they receive, though, with enthusiasts like Elliott-Bowman involved, shinty’s bid to establish itself among the culturally ill-educated south of the border appears to be in good hands.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here