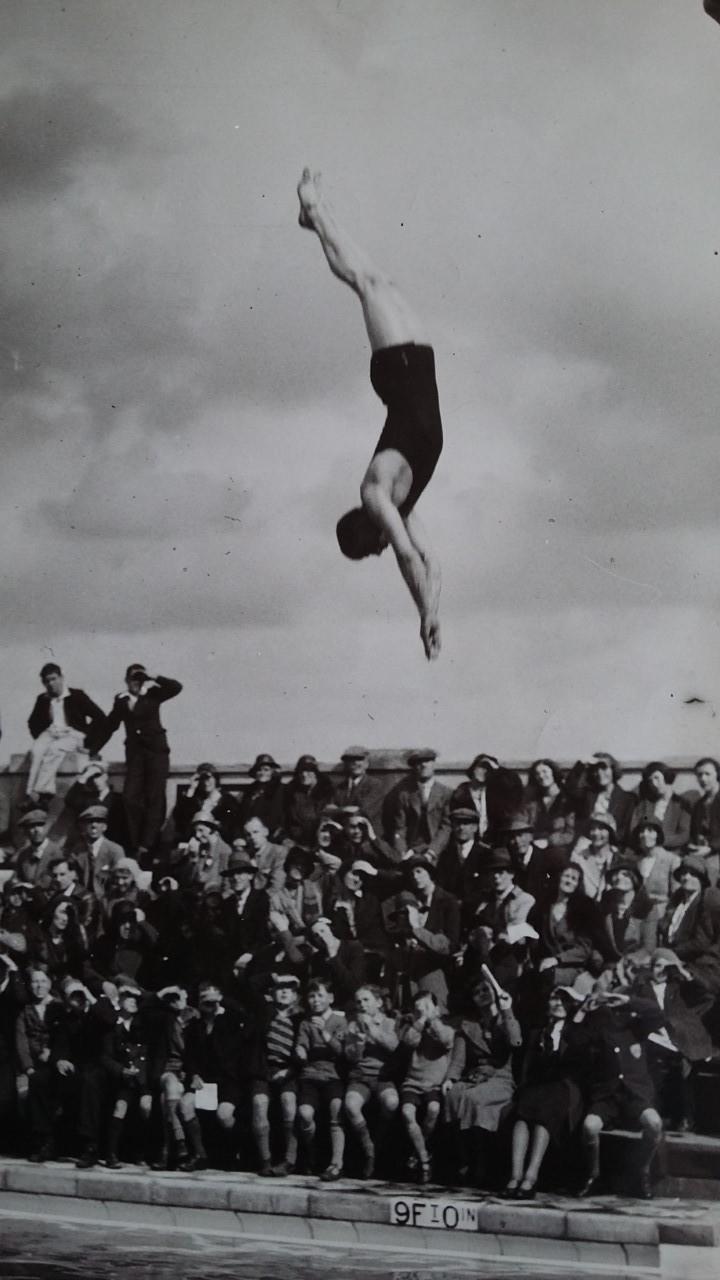

He was known as ‘Dare Devil’ Davie and, quite literally, threw himself into a sporting career when, in his twenties, the great depression cost him his job at the Dalzell Steelworks.

David Crabb had initially been a gymnast who learned to apply the techniques required to a different sport at the Municipal Baths in Motherwell after they opened just as he entered his teens.

He would become a leading light in a diving show which toured the UK in the 1920s, reportedly playing to crowds of 3000 or more at both indoor and outdoor pools, the centrepiece of his performance involving setting himself alight, diving from the highest board or even the rafters of buildings into the pool below to extinguish the flames.

It is hard to imagine modern day health and safety officers clearing that routine and even in those days of Buster Keaton letting houses fall around him and Harold Lloyd hanging from the hands of clocks hundreds of feet above New York, audiences were said to have been shocked by what they witnessed.

Famous or notorious he must have been exceptionally well known in an era when there was a full range of photographic and film technology with which to record his feats. Yet, until earlier this week when North Lanarkshire Council announced its inaugural list of nominees for its ‘Sporting Hall of Fame’, I had never heard of him and suspect at least 99 per cent of those reading this would have to admit to the same.

The nature of their project is, however, very much in keeping with The Herald’s ‘100 Greatest Scottish Sporting Icons’ list which, published earlier this year, could never be comprehensive and was always going to be prey to a certain subjectivity, in spite of having been nominated and voted upon by our team of expert sportswriters.

For the most part those we identified were the best known in the history of Scottish sport, albeit there were many reminders of individuals who had moments of great fame but have slipped from the public eye and memory. There were more than a few, though - the tragic tale of the swimmer Nancy Riach, another North Lanarkshire lass, springs to mind - that were completely new to the vast majority of us.

The timing of the North Lanarkshire announcement was meanwhile given added poignancy by taking place just days after the funeral of Tommy Gemmell and a couple of weeks after it was announced that Billy McNeill, captain of the ‘Lisbon Lions’ was suffering from dementia at a time when he should be among those whose memories are most precious as we prepare to mark the golden jubilee of their achievement. That North Lanarkshire contributed as it did to that team of local boys who did what no other will do again – Jimmy Johnstone and John Clark were the others who played in the final, while John Hughes was a squad member - was a great gift to their community highlighting the real benefit of this ‘Sporting Hall of Fame’ which is the potential impact on civic pride.

The notion that sporting success can somehow inspire mass participation - one of the pillars upon which politicians have long justified vast expenditure on staging sports events - is at best dubious. Indeed, David Crabb unquestionably did better work in that regard when, after what was described as ‘a near miss accident’ he opted for more sensible employment, first as a swimming coach and subsequently returning to Motherwell as Baths Superintendent in 1935.

He was to set up a hugely popular ‘Learn to Swim’ programme, with swimmers transitioning into Motherwell Swimming Club, demonstrating a far better understanding of the issues at play than most modern politicians and sports promoters when observing that: “Every child regardless of background or wealth, should be given the opportunity of bettering themselves, gaining self-respect, health and confidence through organised sport.”

He went on to build one of Scotland and the UK’s most successful swim teams that dominated British, European and World swimming from the 1940s through to the 1960s, his many world-class protégés including Riach, a brilliant talent who contracted polio while competing at the European Swimming Championships in 1947 and died in the pool as she was continuing to compete.

It is those who provide such opportunities who truly inspire future generations, but the real legacy that North Lanarkshire is tapping into by commemorating the achievements of its greatest sportspeople, is to engender that aforementioned civic pride.

Some may consider it frivolous expenditure in light of the pressure being placed on the public purse, but every council in Scotland should be looking to follow the lead of North Lanarkshire in forming its ‘Sporting Hall of Fame’.

In commemorating our icons we give our citizens an enhanced view of who they are and where they come from, which carries huge potential benefits for all aspects of our lives and relationships with the wider world.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here