Billy Connolly has spent nearly his whole adult life painting vivid pictures for his audiences. Almost 50 years ago, as a young, self-styled, long-haired, wandering-minstrel banjo player in folk clubs in and around Glasgow, the former shipyard welder would take his audiences on a stream-of-consciousness comic journey as a way of drawing them into his world.

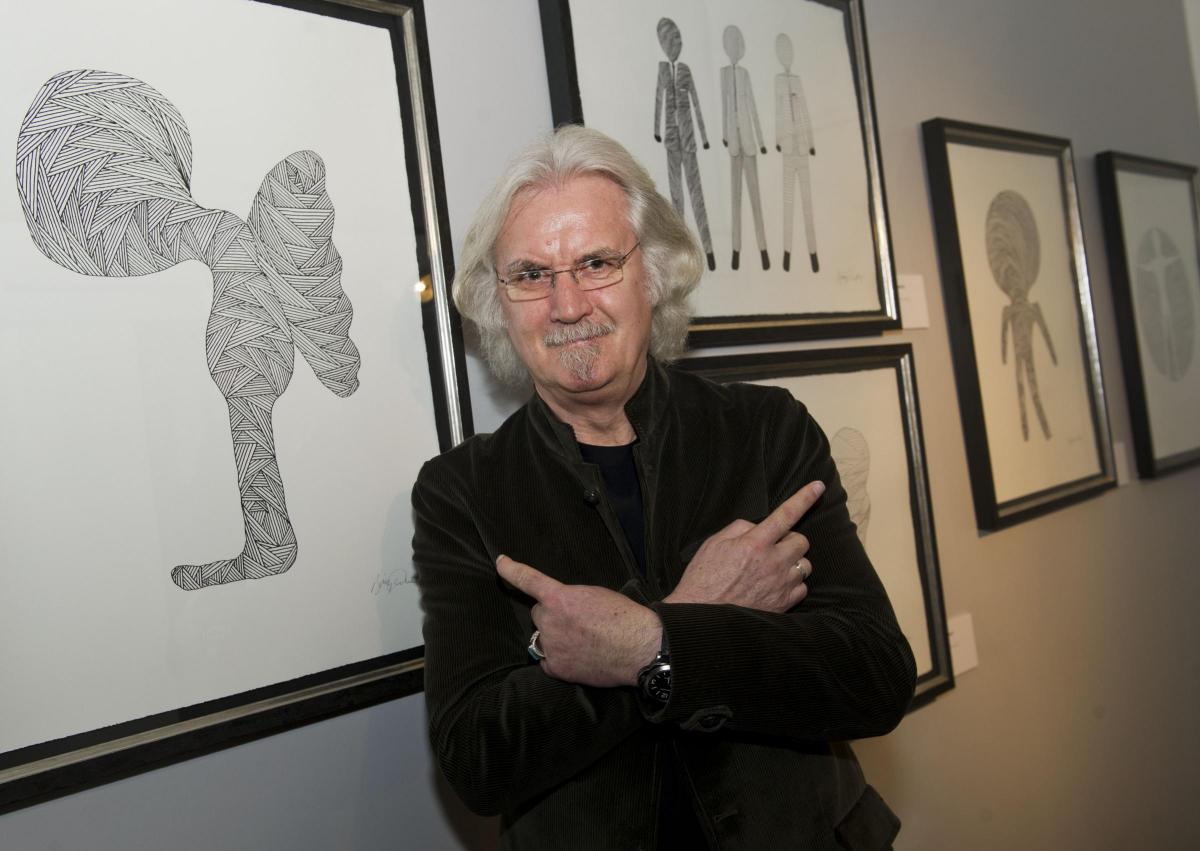

Now, in his old age, 72-year-old Connolly has turned to making marks on paper as a way of working out what makes the world turn on its axis. And thanks to a new exhibition which opens at the People's Palace in Glasgow on Friday and runs until February next year, the public will gain a unique insight into the constantly whirring creative cogs which make The Big Yin tick.

The exhibition, called The Art Of Billy Connolly, also offers an opportunity to see a side to the man that many will not recognise: that of the introspective artist. More than 40 original Connolly artworks will be on show, courtesy of art publisher Washington Green. There is also an opportunity to buy signed limited edition prints of his work if you have a spare few hundred pounds.

Connolly always dabbled in drawing. People who knew him when he was a young apprentice welder in John Brown Shipyard, Clydebank, recall how he and fellow tradesmen, including the father of acclaimed New Glasgow Boy artist Steven Conroy, used to draw caricatures on the bulk heads of the giant ships built there. Although he was always surrounded by artists and even presented a series for BBC Scotland about Scottish art in 1994 called The Bigger Picture, Connolly didn’t start drawing in earnest until 2007.

The story goes that while on tour he wandered into an art shop in the Canadian city of Montreal and bought up bagfuls of art materials. He headed straight back to his hotel room and started to just draw whatever came into his head. He began by sketching desert islands, one after the other, each island taking on its own characteristics and personality. “The fifth island, I noticed, was considerably better than the first one,” Connolly recalls. At every opportunity since, he has sketched and drawn characters from his imagination.

Talking about his drawings, Connolly, who was signed three years ago to Washington Green, one of the UK’s leading fine art publishers, said: “I don’t want them to be judged. I didn’t want to put them in a position where people would like or dislike them. They’re little pals of mine. I’ll always draw, I’ll always do it.”

Connolly’s love affair with the art world has been a slow-burning one. He was a bright spark as a child growing up in Glasgow, and his actress-turned-psychologist wife, Pamela Stephenson, puts forward the notion in her 2001 biography, Billy, that today her husband might be described as having Attention Deficit Disorder.

From his early days playing gigs around the west of Scotland folk scene, Connolly hung out with the Glasgow arty crowd. After leaving The Humblebums, a band he started up in 1965 with a guitarist friend Tam Harvey, and which ended up featuring another west-coast minstrel pal, Gerry Rafferty, he became known universally as The Big Yin. His rambling riffs on the peculiarities of mankind through detailed observational humour were fresh and original. As time wore on, this imagery-soaked patter became his calling-card.

He looked the part too. Connolly’s on-stage costumes bore the mark of an artist-at-work. Once registered, the mental picture of a six-foot-tall, long-haired, bearded man wearing a black one-piece leotard and giant boots which looked like bananas, could not be forgotten.

His day-to-day look was also Bohemian for a former welder. Wearing what his wife later described as "windswept and interesting" garb, he became a key player in burgeoning Glasgow arts social scene of the 1970s. He regularly played gigs at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) and figures such as artist and writer John Byrne and influential textile artist and GSA teacher Chuck Mitchell were among his inner circle of close friends. Byrne created album covers for The Humblebums and painted several large-scale portraits of his friend, including a huge portrait done in 1974, now on permanent display at the People’s Palace.

Connolly’s first manager was Frank Lynch, a colourful character known in Glasgow as "the disco king". Lynch, now a successful businessman based in the US, bought a dilapidated cinema called Green’s Playhouse and converted it into legendary Glasgow music venue, The Apollo.

Lynch also created Glasgow's first "pop art pub", The Muscular Arms in West George Street, which featured outlandish, yet well-before-their-time design touches, such as a fur fabric King Kong holding up a blown-up photograph of the Muscular Arms building cracked in the middle and emitting red splotches. It was a hang-out for the Glasgow arty crowd, of which Connolly was an enthusiastic member.

It was an appearance in 1975 on the UK-wide Saturday night TV chat show hosted by Michael Parkinson which sealed Connolly’s reputation nationally as a trail-blazing comic with his own unique improvisational style. He told a joke about a murdered wife, a bum and a bike which had Lynch cringing in fear, worried his talented client’s career might be over before it started.

It was just the beginning. A 40-year-long career as comic, musician, writer, television presenter and award-winning actor followed on.

On show alongside the Connolly drawings at the People’s Palace exhibition will be objects from Glasgow Museums’ collection relating to his early career as a comedian and musician, including his famous Big Banana Boots, one of the People’s Palace most popular exhibits.

The banana boots were designed and made for Connolly by the Glasgow pop artist Edmund Smith. Connolly knew Smith through Frank Lynch, and in 1975 he ordered a pair of size nine ‘bananas’ from Smith.

On completion of the first banana, the artist cautioned that the second one would not be identical and so the second banana was given "designer status" by the addition of the famous Fyffes label. The boots made their first appearance on stage at the Aberdeen Music Hall in August 1975. That same year Murray Grigor and David Peat filmed a documentary about Connolly on the road, called Big Banana Feet.

Other objects on show include some of the collection's buried Connolly treasures: a purple satin costume with gold lurex star worn by Connolly on stage; a guitar made out of a White Horse whisky box; various memorabilia including programmes for The Billy Connolly Show 74 at the Pavilion and his 1976 play An Me Wi’ A Bad Leg Tae, created for Borderline Theatre with cover artwork by his friend, the cartoonist Malky McCormick. (Connolly and McCormick also devised, drew and wrote the hugely successful cartoon strip The Big Yin, which ran for many years in The Sunday Mail).

There will be some examples of the artist's early recordings, including a copy of The Welly Boot Song single, released in 1974 and in the charts early the following year, and an album cover for Billy Connolly Live! recorded at City Hall Glasgow on August 6, 1972. This was the album which Michael Parkinson was famously given by a Glaswegian taxi driver who insisted that if he liked comedy then he should give it a whirl.

As Glasgow Life curator Fiona Hayes says, “Billy Connolly was always a creative person, but the drawing just seemed to happen a few years ago when this 'automatism' process of letting the pen go began. The drawings tie in with his persona; his anarchic view of world. I think this will be a really popular exhibition, highlighting as it does so many aspects of Billy’s creativity and self-expression.

“The items on show from Glasgow Museum’s collection relate to his career when he took the Glasgow style of humour and became figurehead for anarchic and ‘real’ humour. He himself has said he took old man's patter from shipyards and the communities he grew up in and then got much better response to his stories than his music when he played folk clubs in the 1960s and early 1970s. This led to stand-up, acting and all the rest.”

Talking about his famous client’s work, Ian Weatherby-Blythe, managing director of Washington Green Fine Art, says: “Billy’s art can be recognised as creativity in its purest form. It has come from a place inside the artist that is not concerned with an audience or showmanship. It is not driven by a reaction or approval. His characters are faceless and anonymous, and yet the emotional connection with the audience is quite prevalent. It is perhaps the simplicity of these characters that allows the viewer to connect with them so deeply.”

Looking at these drawings is almost like looking at a visual equivalent of an on-stage Connolly anecdote. Rambling yet curiously controlled, they keep coming back to an innate curiosity which lurks in every corner of an extraordinarily creative mind.

The Art Of Billy Connolly is at the People’s Palace, Glasgow Green, from August 28 until February 21, www.glasgowmuseums.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel