The issue of Britain's role in the slave trade has returned to the headlines, with calls for the UK to pay reparations to Jamaica. In tomorrow's Herald Magazine, Scotland's foremost historian Sir Tom Devine reveals the true extent of Scotland's involvement. Here, we look at how Glasgow - and Scotland - was shaped by the trade - and the men who benefited from other people's misery.

In his 2009 book, It Wisnae Us: The Truth About Glasgow and Slavery, Stephen Mullen said that Glasgow and her merchants monopolised the two main goods produced by slaves - tobacco and sugar. He added: "There are many reminders of this controversial past in daily view in Glasgow. The built heritage betrays much of this history in its street names, churches, graveyards and in the remains of Palladian mansions. That Glasgow benefited is indisputable."

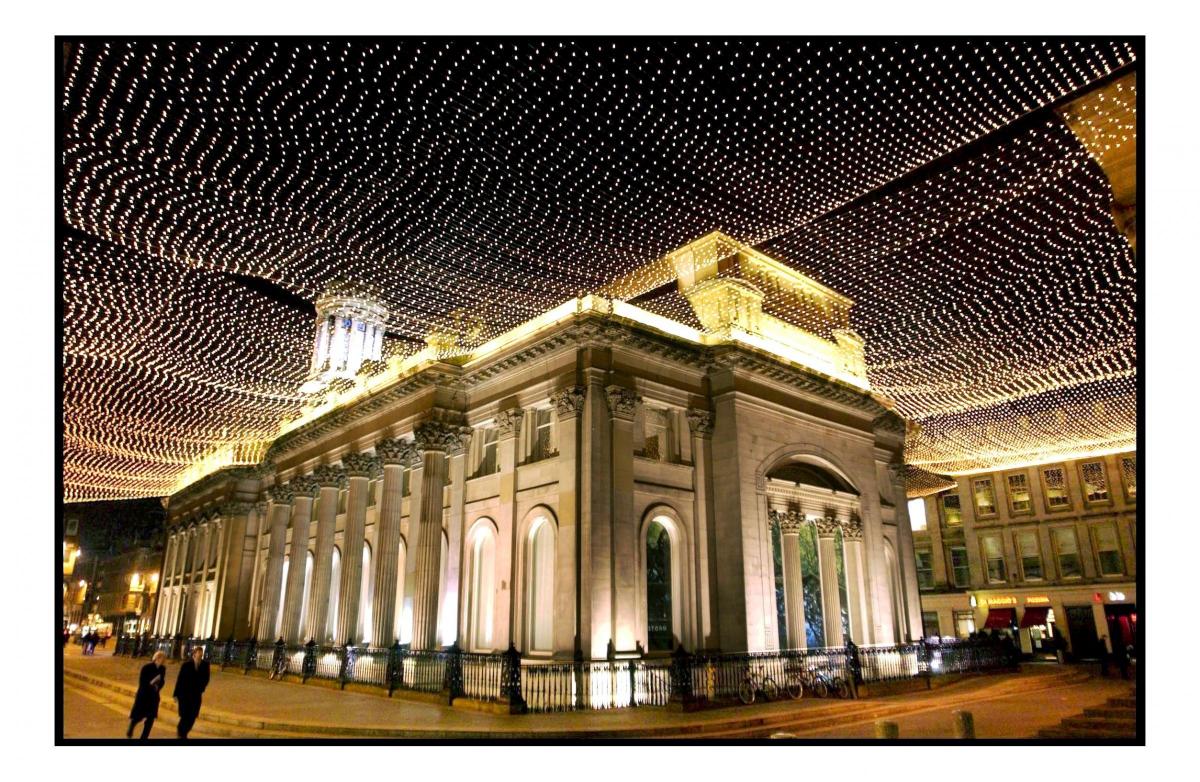

Mullen says the building that houses the Gallery of Modern Art, one of the city's most-visited attractions, "has a long connection with slave plantation economics." The Cunninghame Mansion, now the core of the building, was constructed in 1778 for William Cunninghame of Lainshaw, one of Glasgow's leading merchants. He had "significant" interests in both the Virginia tobacco trade and the West Indies sugar trade, Mullen added. He owned one plantation in Westmoreland, Jamaica, which had 300 slaves.

James Ewing, an influential Glasgow citizen, was Lord Provost of Glasgow and an MP. He too, was a slave plantation owner. He also served as chairman of the city's Chamber of Commerce, and was a key figure in the development of the Glasgow Necropolis.

Jamaica Street was named after the largest slave plantation in the Caribbean, Mullen says.

Many other parts of modern-day Glasgow carry echoes of merchants who were associated with the tobacco business or the Caribbean sugar business, both of which were utterly dependent upon the enslavement of black people.

Among them are Buchanan Street, Virginia Street, Glassford Street, Ingram Street and Tobago Street.

The magnificent church of St Andrews in the Square was funded by colonial merchants.

Kingston Bridge, too: Kingston is the capital of Jamaica, and refers to the former Kingston dock on the Clyde.

Richard Oswald worked for his cousins’ Glasgow-based merchants’ firm before, in 1743, in London, setting up his own company, working in tobacco and then in slaves, horses and sugar. A key source of his wealth was the establishment of a slave ‘fort’ on Bance Island, off the coast of Sierra Leone. During its period of activity, some 30,000 Africans were exported from it to the Caribbean.

Oswald retired to Auchincruive, in Ayrshire, where the agricultural college now stands. The Oswalds have a family burial plot in Glasgow Cathedral, though Richard himself in buried in a parish church in Ayrshire.

By Russell Leadbetter

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here