“We are time travellers,” says Robert Nizinski, multi-instrumentalist in the Polish avant-garde band Ksiezyc. “We bring in ancient and modern elements, elements taken from the cosmic universe and from our local roots.” Alright: out of context this statement might sound inexcusably wide-eyed, and admittedly it’s the kind of quote I’d usually try to bury further down in an interview. But as a broad summation of the singular, surreal and totally beguiling sound of Ksiezyc — think medieval Slavic chant fused with American minimalism topped with expressionist Sprechgesang — it is actually a pretty good place to start.

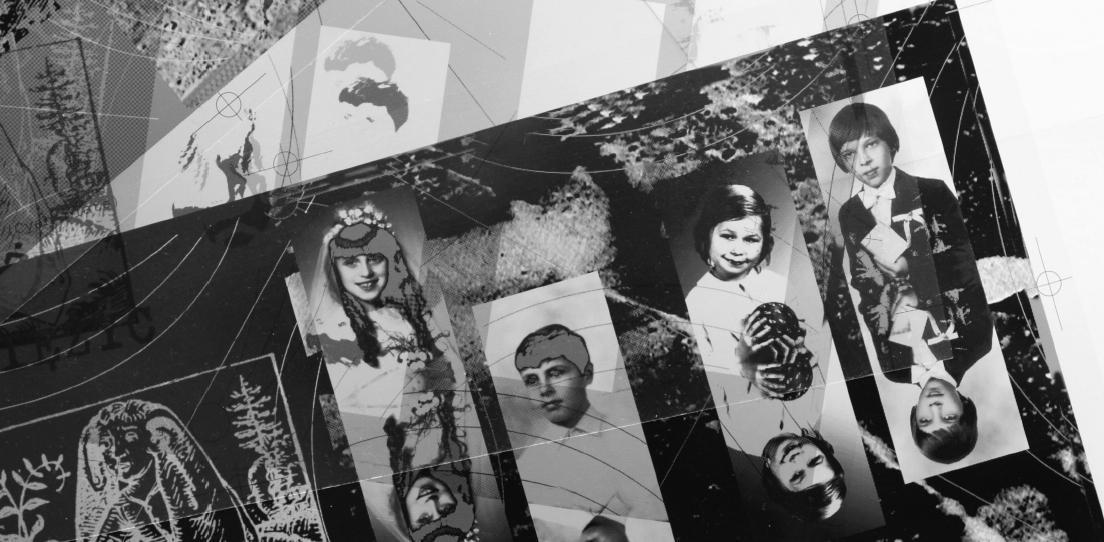

Ksiezyc means moon in Polish. The ensemble formed in the 1990s as members of a Grotowskian student theatre troupe and soon began performing skits and traditional Polish and Ukrainian song on the streets of Warsaw. A self-titled debut album gain cult status in Poland and internationally, with devoted fans that the band now fondly describes as “poetry seekers, dreamers and people dressed in black”.

One listen and it’s obvious why the fandom. Ksiezyc is an absurd and eerily beautiful blend of medieval church music, minimalism, electro trance, traditional song, 20th century experimental vocal techniques and more. This is a band whose members quote Hildegard von Bingen, Orlande de Lassus and Thomas Morley as influences alongside pioneering US singer Meredith Monk, Brixton radical rockers This Heat and traditional folk dance from Poland, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Ukraine and the Sahara. It’s some cocktail: dark and sweet and macabre, earthy, timeless, placeless and stark.

Lyrics on the original album tell coming-of-age stories, stories about “little girls experiencing a world that is scary, lonely and has to be tamed in some way,” explains singer and pianist Katarzyna Smoluk. “The texts complement the dreamy character of this music,” she says, “but they could be independent poetry as well, at least the ones written by Remek Hanaj” — another member of the band, responsible for lyrics as well as adding tape loops, samples and ambient sounds to the mix. Smoluk says the band is inspired by playground games and enjoys “reworking creepy nursery rhymes”. And she’s right: creepy is the perfect word for those wailing voices on Chodz, for the wan, breathy bass clarinet lines on Lalka (a track punctuated with demonic laughter) and for the panting hockets, childlike humming and menacing processionals on Dychana.

Ksiezyc performs in Glasgow University Chapel next week, part of a three-date UK tour to mark the band’s regrouping after 20 years and the long-awaited release of a second album, Rabbit Eclipse. Nizinski says the acoustic and atmosphere in the chapel will be ideal. “Old churches, catacombs… Sacred spaces affect both our audiences and ourselves. They make us more attentive; they put us in the right contemplative mood.”

For me the key aspect of the Ksiezyc sound is the vocals. Smoluk and her fellow founding member, Agata Harz, pin high, fragile melodies or steely plainchant or swooping shrieks above the band’s grimy drones and warped clarinet lines. “I think it's a natural mix of our origin and experiences,” Harz explains when I ask about the vocal techniques they use. “I had contact with different kinds of music and different ways of singing from childhood. Both of my grandmothers were good village singers: they were Polish women born in Lithuania and Belarus. I myself was born in Cairo and my nanny was Sudanese. All of that allowed my mind and my voice to really open, and I joined those early experiences together with classical music and traditional ‘open voice’ singing in a way that is just organic for me.” She says Meredith Monk — American composer, producer and towering figure of extended vocal techniques — is her “absolute idol”, and I would say that it shows.

I’ve read interviews with Ksiezyc that that suggest the name, Moon, is a feminist symbol, but Harz is quick to refute this. “In the beginning we were just three young, female friends looking for the meaning of life — ha!” she laughs, presumably at her own student-day nativity. “Whatever it was, we were trying to find it in theatre and traditional Ukrainian and Polish song. That’s all.”

Smoluk agrees. “In most languages the Moon is female, but not in Polish. There were three women in the band at first and the name suited us perfectly, but it was just a coincidence. Anyway,” she continues, “the texts that expressed the feminine character of the group were written by a male, Remek. So talking about a feminist statement misses the point, even though I assume that our music appeals to some inner female element in both men and women. We don’t want to categorise our music according to gender.”

I get the sense that the musicians of Ksiezyc don’t want to categorise their music according to anything much. Certainly the band — formed in a Poland just emerging from communism, now regrouping in Poland ten years into EU membership — has been careful to avoid touting any obvious sociopolitical agenda. “We do not manifest anything,” says Smoluk. “We just care about our independence as artists.” Nizinski stresses that there’s no narrative, no explicit cultural commentary. “You cannot hear it in our music,” he says. “It isn’t there. The Moon was and is distant from political and cultural contexts.”

I get a similar response when I ask whether the band exists within any ecosystem of Polish contemporary music. “Ksiezyc is, as always, out of any system,” Harz says. Yet all of the members work separately on projects in theatre, traditional and experimental music. Hanaj spent years making field recordings in Polish villages which he then released in a 20-part CD series and used as samples in his own compositions. Nizinski collaborates with filmmakers and visual artists to make sound installations and movie soundtracks. “I try to explore various areas from avant-folk through minimal, repetitive, bricolage and underground techno techniques,” he explains. “I use field recording and sound experiments with objects. In recent audio-visual projects I’ve been investigating the possibility of quasi-holographic simulation of presence,” he adds, somewhat mystifyingly.

Can any music exist entirely out of time and place? Nizinski will go as far as acknowledging that Ksiezyc “is now linked to some folk and experimental communities, mainly connected with Polish labels like OBUH and Monotype. Maybe we can say we represent Polish music off-culture, maybe a niche and underground scene here. But really,” he concludes, “we occupy our own different stylistic category.”

The new album is a reunion and a departure. The music has become freer and more improvised. “We are more artistically conscious and less afraid of boring people by long sequences of repetitive sounds,” Smoluk says with a smile. “There are fewer lyrics, and the lyrics that we do have are pretty different from the ones we sang 20 years ago.” Hanaj, responsible for many of those lyrics then and now, sums up the themes of the new album as dealing with “the mystery of live and death, good and evil, transformation and expectance. There are no more little girls singing about growing pains,” he says. “No more songs about the tragedies of their little lives.” ?

Ksiezyc plays at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival on 23 November, Glasgow University Chapel on 25 November and Cafe Oto, London, on 27 November

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here