The long journey is almost done and Long Earth ready to take back its guest. Joshua Valienté, cosmic orphan and latter-day Huck Finn, but now grown old and tired, takes one last journey out into the High Meggers to face his own extinction. More than five decades have passed since Step Day, when the doors to Long Earth swung open and mankind began its stepwise progress into a quantum polyverse of replica Earths with nothing in common except that none of them has evolved Homo sapiens. The chain of such worlds is possibly infinite and unbroken, save in the Gap, where one is missing, smashed by an asteroid. Our familiar world, known as Datum Earth, has avoided destruction, but not decay, its inhabitants tired, dysfunctional, remote from one another, caught between nostalgia and a new frontier.

“Stepping” is facilitated by a simple technology, but there are natural steppers, too, and Joshua is unique in being born off-Earth when his mother stepped at the moment of childbirth. The Long Cosmos finds him widowed, remote from his son, surrounded by ageing friends and replicant versions of the nuns who raised him in the orphanage. He lights out for the least human environment he can find . . .

. . . but at the same time the Long Earth receives a message, picked up by powerful scanners but also intuited by the hominid trolls and Great Traversers. It seems to come from the region of Sagittarius, towards the centre of the galaxy. It is simple enough, but it braces rather than consoles. It says “JOIN US”. And so, at the end of the journey, there is a new journey proposed.

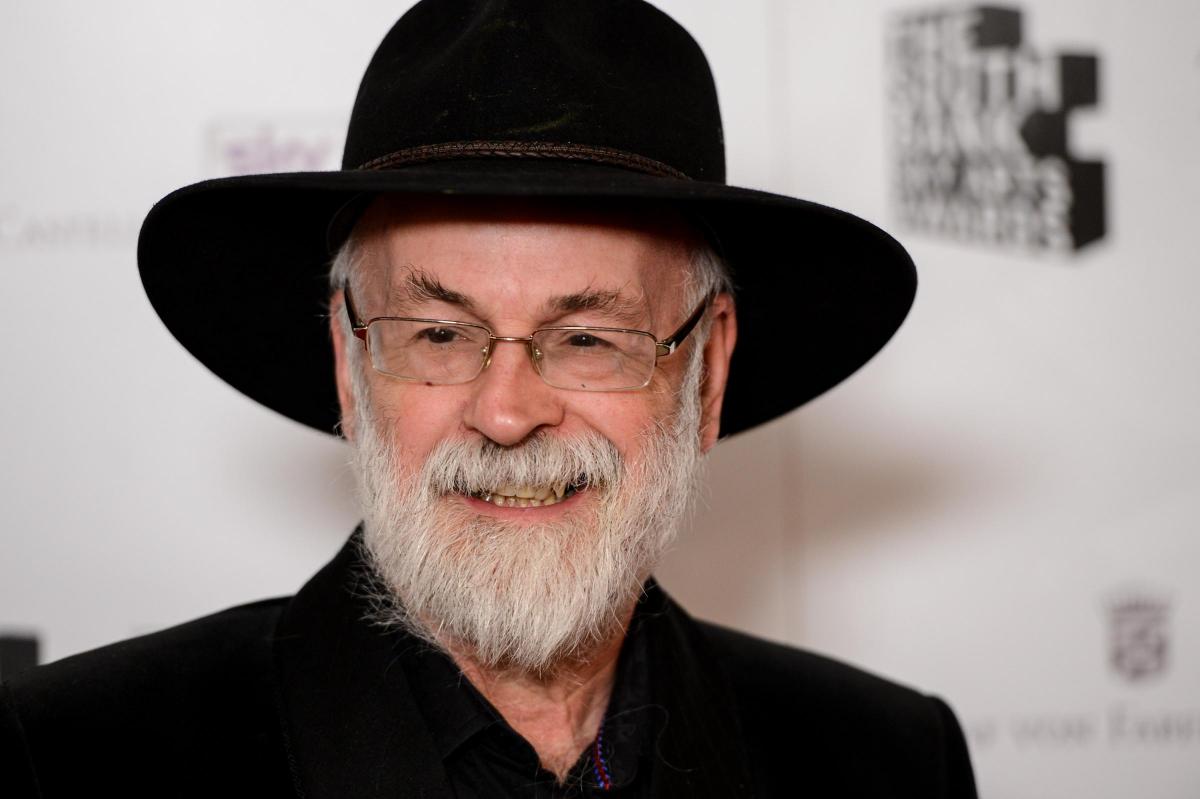

This is not, obviously, a Discworld novel, and to that degree not really a Terry Pratchett novel at all. It was completed, in some haste, by the collaborators while Sir Terry’s dignified struggle with Alzheimer’s played out and the final editing and checking has been done by Stephen Baxter since Sir Terry’s death. And it feels very much more like a Baxter novel, its variation on the Fermi paradox – there must be intelligences out there, masses of them, but why do we never hear from them? – familiar from Baxter’s Manifold sequence. Yet it is full of Pratchett’s metaphysical satire and playfulness.

The artificial intelligence which governs Datum Earth is called Lobsang, a cheeky reference to Tuesday Longsang Rampa, the enlightened lama who sold shelfloads of books to credulous Britons in the 1950s but who turned out to be a plumber from Devon called Cyril Hoskin; the Pratchett and Baxter “Lobsang” is apparently the reincarnation of a Tibetan motorcycle repairman, which makes us think in turn of Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. There are devices called “twains”, just in case we’re missing the Huck Finn/Tom Sawyer parallels. And so on.

More daringly referential is the basic plot itself, which owes a debt to Carl Sagan’s Contact, where there is a similar cosmic hello and handshake and a similarly faxed-down set of instructions, though this time it’s for a continent-wide super-computer rather than a one-person space-time machine. But Pratchett and Baxter cleverly weave the film version of Contact into the story, where it’s watched with fascination by another orphan savant who like Sagan’s Ellie Arroway obsessively searches for patterns in things. As most readers will be aware, Sagan was among the chief of the “contact optimists” who believed that the interstellar transport infrastructure and mail service would one day grant us a one-to-one with another intelligence, while Stephen Hawking remains one of the more vocal “contact pessimists” who believes they may be out there, but too far away, too under- or over-developed, too busy or too damn lazy to contact a pale blue blob set alongside a very middling star.

Baxter’s imagination is perhaps more literary than Pratchett ever found a need to be, though in an entirely positive way. The whimsy of Discworld sometimes lacked fibre and chew and there’s plenty of that here. And of course behind all the deliciously clunky and head-messing technology, beyond the speculative science of multiple, simultaneous universes and quibbles about cats in boxes, dead or alive, there is a simple humanity at work. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is a popular science favourite, but both these writers know that human consciousness is the uncertainty principle and that the imagination, which can make the cat live or die, as a Persian or as a feral moggie, is always there to take us beyond the mundane and quotidian. Writers are steppers, by definition. Datum Earth is rich in archived imagination, but the Long Earth and beyond that, the Long Cosmos offers even greater satisfactions. To some, the appeal of these books, as of the Discworld novels, will be as mystifying as their theoretical underpinnings, but read acceptingly and with the same measure of identification and empathy one would show to a well-rounded character in a realist novel, they reveal much about who and what we are, and what we might still become. At the end of a cycle and a life, here’s a book about growing up, growing old, shuffling off, and all the happy, scary things in between.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here