By Alan Taylor

WHEN in 2013 Alice Munro announced she was capping her pen and would write no more the overwhelming reaction was one of sadness. At the age of 82, and having won every major literary award from the Nobel to all the bouquets her native Canada had it in its gift to throw at her, she was adamant she was calling it quits. Her bereft fans, however, took a soupçon of comfort in the fact that she had said the same before only to resume where she left off.

The problem, she said, was that she kept having ideas for stories and could not resist exploring them. As long ago as 1994, when she had first considered retirement, she realised that it would be far from easy. “It’s not the giving up of the writing that I fear,” she said. “It’s the giving up of this excitement or whatever it is that you feel that makes you write. This is what I wonder: what do most people do once the necessity of working all the time is removed?”

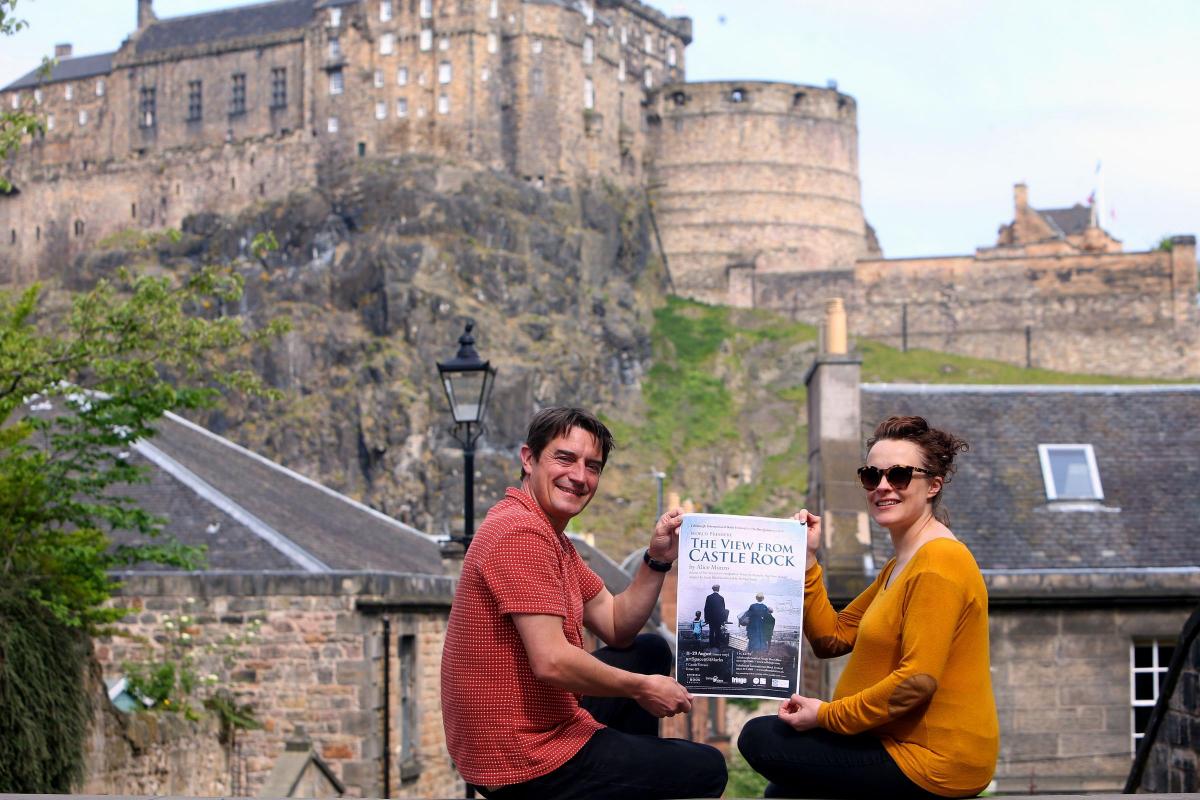

The esteem in which Munro is held may be gauged by the fact that while she is not appearing herself at the Edinburgh International Book Festival – which she has never done – she is top of the bill. In the absence of the woman herself, Stellar Quines theatre company is staging an adaptation of The View From Castle Rock, a melange of history, memoir, myth and fiction published in 2007. In it, Munro looks back on her Borders ancestry and the consequences of a decision made in the second decade of the nineteenth century to emigrate to Canada in search of a better life.

It was her forebear, one James Laidlaw, who is responsible for her being a Canadian. In 1818, he uprooted his family from the Ettrick Valley and travelled west, ending up in a corner of Ontario which lies midway between Toronto and Detroit. Today it is associated with a short story writer who is its atomist and celebrant. Munro County, as it may well be renamed in future, is a place as flat and featureless as the Netherlands, where the roads run straight as an arrow for mile after mile and nothing much seems to happen beyond yard sales and church services. For the moment, however, it it is called Huron County where, as Margaret Atwood has noted, you are likely to see signs in wheat fields telling you to be prepared to meet your God, “or else your doom – felt to be much the same thing”.

But as Munro’s devoted readers know well, where there are people things do happen; accidents, unions, partings, anniversaries, bankruptcies, love affairs, job losses, major and minor misdemeanours. Often her principal characters are women fearful of being left on the shelf or who have become dissatisfied with their lot in life and hanker for more – whatever that is. In an essay titled ‘Working for a Living’, Munro recalled how as her mother grew older she had unrealistic pretensions to a genteel, middle-class existence, which included funding a school bursary on the basis of the family’s fox-fur business. That it had rarely broken even was immaterial. Such pride, such profligacy in the face of poverty, Munro reflected, bordered on perversity.

What is most impressive and compelling about the way she writes is the steadiness of her tone and how she resists any temptation towards sentimentalism. Like the pioneering Laidlaws, she knows that it is pointless to complain. If you want to survive you must knuckle down and deal with whatever is thrown at you as best you can. Two hundred years on little in essence has really changed. Immigrants want to better themselves and will seek to do so wherever they think that a possibility.

Alice Munro, née Laidlaw, was born in 1931, and grew up during the Depression. She attended the University of Western Ontario where initially she studied journalism before switching to English. By 20, she was married and she had her first child, a daughter, two years later. By then, though, magazines had already begun to appreciate her stories. A second daughter died the day she was born; a third was born in 1957. In 1963, she moved with her family to Victoria where she and her first husband, Jim Munro, opened a bookshop, Munro’s Books, which is still trading. Another daughter was born in 1966.

Munro’s life was thus one in which motherhood and domesticity were combined with writing and thinking about writing. Like Chekhov and Cheever, with both of whom

she is routinely compared, she prefers suggestion to specificity. She never spells out what’s going on in a story, preferring to leave it to her readers to figure it out for themselves. Religion is a hammer used to nail down sinners. Shame and humiliation are hurled from the pulpit. Sex is never far from the surface. Secrets are kept until they need to be used, like poisoned darts. Women look on other women as rivals and predators while men strut like peacocks and lie like snake oil salesmen. “A rumpled bed says more, in the hands of Munro,” Atwood has remarked, “than any graphic in-out, in-out depiction of genitalia ever could.”

Moreover, there is nothing neat and tidy about Munro’s world. It is inchoate, chaotic, ongoing, asymmetrical. Rarely does she tie up loose ends, life goes on, you feel, even after she makes the last full stop. Often her stories begin in the middle of scenes so that when you start to read one you are immediately involved in it. ‘Miles City, Montana’, a personal favourite, begins: “My father came across the field carrying the body of the boy who had drowned.” Another superb one, ‘The Progress of Love’, opens: “I got a call at work, and it was my father.” It transpires that the narrator’s mother has just died. Yet another, ‘Nettles’, starts: “I walked into the kitchen of my friend Sunny’s house near Uxbridge, Ontario, and saw a man making himself a ketchup sandwich.” In each case you want to know what happens next. Great writers such as Munro write the kind of unfussy, informative sentences that insist you read on, creating their own restless momentum.

The year Munro announced she was calling it a day coincided with the award of the Nobel. True to form she did not travel to Stockholm for the hoopla. Instead she consented to be interviewed by video. “Stories,” she said, “are so important in the world, and I want to make up some of these stories...In a way, it didn’t have anything to do with other people.” It is, she recognises, a timeless occupation which is in her genes. In The View From Castle Rock she relates how she spent much time in Scotland poring through family papers and public records and immersing herself in the Borders, its ballads and battles. Among the branches in her family tree is one reserved for James Hogg, author of Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Munro visited his grave in Ettrick churchyard and that, too, of “the far-famed” Will o’ Phaup, Hogg’s maternal grandfather, who was reputedly the last man in the area to converse with the fairies.

There is no such nonsense in Munro’s make-up. Her world is real but imagined. Her stories, like Thomas Hardy’s, come from the place in which she is rooted. But anyone who has tried to make a direct connection with actual events and people has found it frustrating. For, as Margaret Atwood has said, in the work of Alice Munro, “a thing can be true, but not true, but true nonetheless.”

The View from Castle Rock is at artsSpace@StMarks, 7 Castle Terrace, Edinburgh, until 29 August

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here