THEIR flat was small, Leonie Orton tells me. Just one room really. A kitchenette on one side, a little desk, a typewriter and two single beds: one for her brother Joe, as in Joe Orton, the playwright, diarist, vandaliser of library books and lover of men, and the other for Kenneth Halliwell, Orton’s mentor, boyfriend and, eventually, his killer. When the couple were found, Orton was lying on his bed, the right side of his head staved in with a hammer; Halliwell was on the floor, dead after overdosing on 22 sleeping tablets. He’d left a suicide note. “If you read his diary all will be explained,” it said.

It is now 50 years since that notorious murder at 25 Noel Road in London on August 9, 1967, and the killing of Joe Orton has been a central incident in gay history ever since, as well as the history of the theatre, literature – and sex. When he died, aged 34, Orton had already achieved much of his potential as a great comic playwright and dramatist and was ready to achieve more. His plays, such as Entertaining Mr Sloane and What The Butler Saw, were wild, outrageous, rude and successful, and so was his private life at a time when sex between men was still illegal and often prosecuted – it was partly decriminalised the year Orton died.

His diaries reveal the details of Orton's promiscuous sex life, as well as his difficult relationship with Halliwell, and they have since become a classic of 1960s literature, an inspiration to gay men, and a textbook for sexual adventurers. “Samuel Pepys put all his references to sexual matters in code so that no one would know,” Orton once said. “I don’t care who knows.”

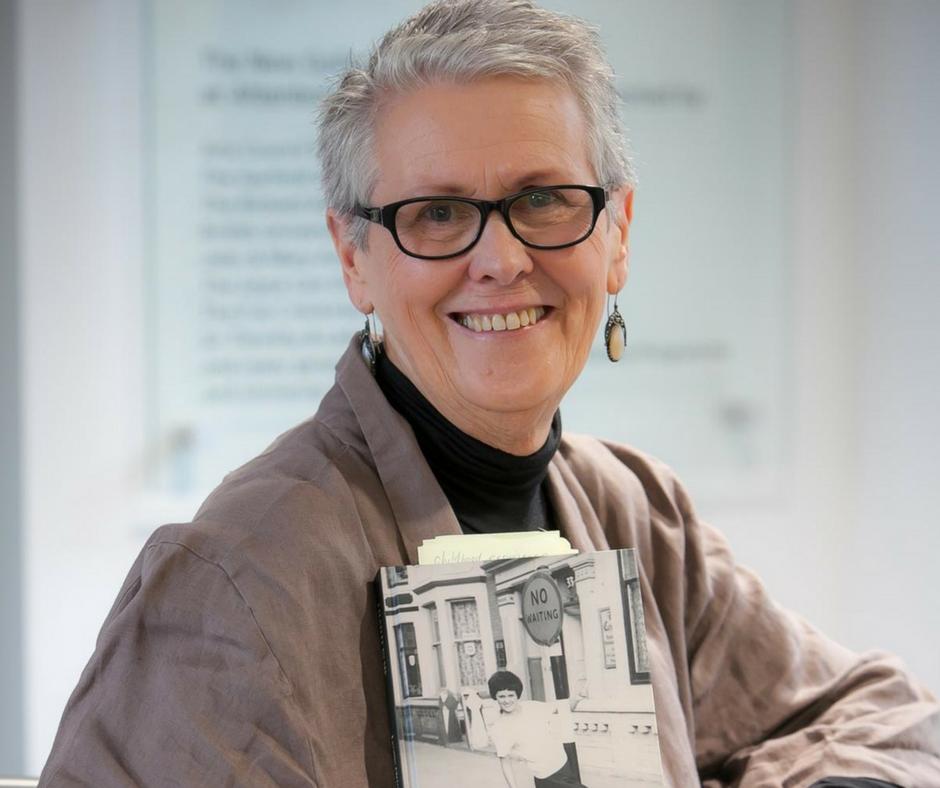

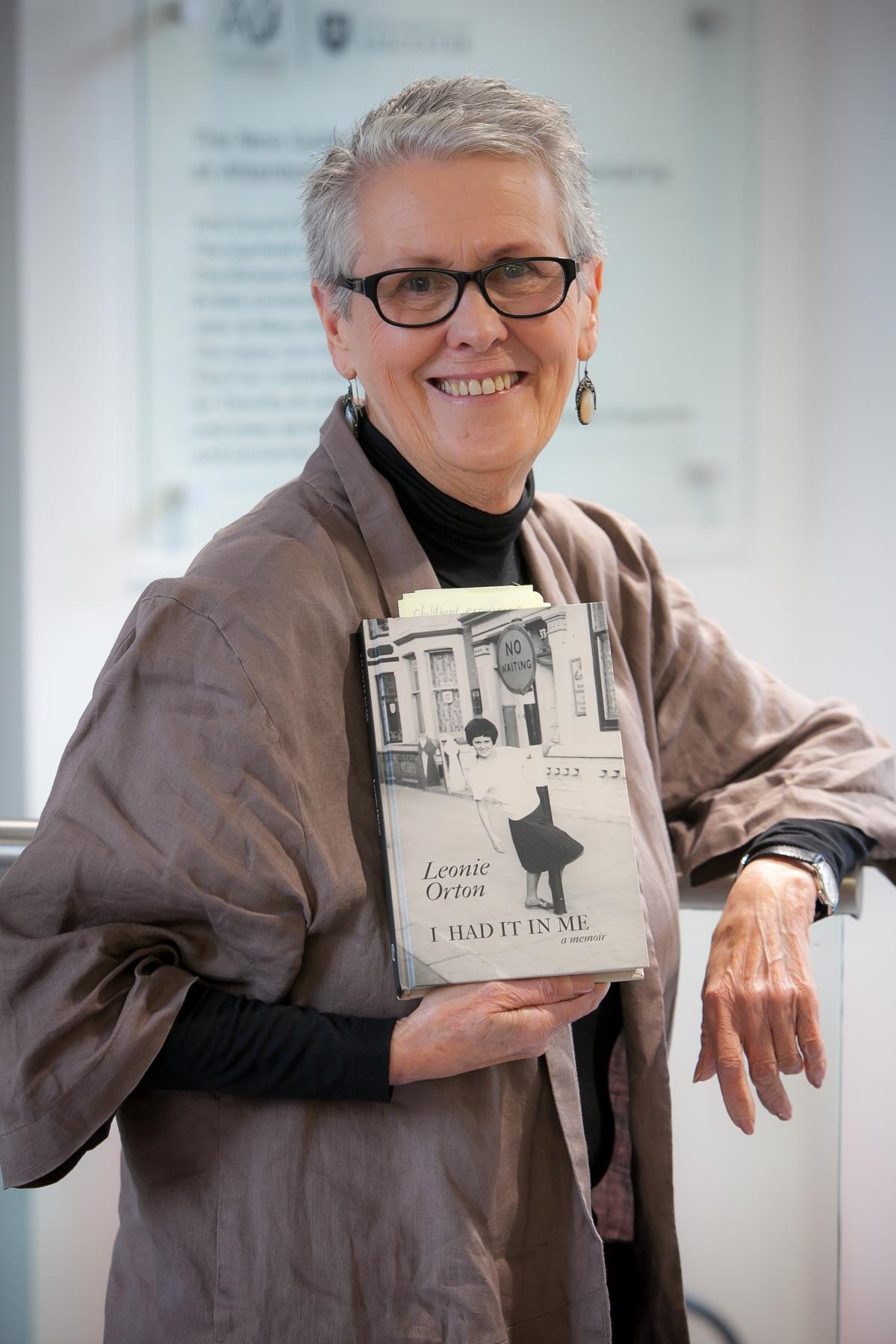

But Orton’s diaries also represent – even now, 50 years on – something of a mystery, which is one of the reasons I’m meeting Orton’s sister ahead of the anniversary of her brother’s death. Leonie is now the keeper of the Orton estate and there are big plans for the anniversary year, but the mystery of the diaries is still one of her main motivations.

According to that brief suicide note from Halliwell, who had been on anti-depressants and at the time of his death was due to go into a psychiatric hospital, the diaries should explain everything about why Joe Orton died. But, as anyone who has read them will know, they don’t explain everything at all, and Leonie believes that’s because there are pages missing – critical pages from the last few days of her brother’s life. Leonie thinks there’s still a chance those pages could turn up and she’s constantly on the look-out for news, she tells me. Her ears, she says, are always in the pricked position.

I’m meeting Leonie Orton in Norwich, where she now lives, and it doesn’t take long to spot the similarities with Joe even though she’s 72 now. For a start, she looks a bit like him, especially the big doll eyes that widen and then narrow to dashes. She also shares some of her brother’s personality traits and habits: the suggestive wordplay (the title of the book she wrote about her life is called I Had It In Me); the straightforward attitude to sex and love; and a certain emotional detachment that she says comes from their poor upbringing on a council estate in Leicester.

She tells me, for example, that she can’t abide people treating their dogs like little children – they’re dogs, not companions, she says, and, in a way, Joe Orton had the same attitude to humans. In the diaries, he talks about his view of a potential conquest called Clive. “All I want is a bit of a knock with him,” he writes. “I’m not interested in futile relationships.”

Leonie believes some of this attitude from her brother was an act; Joe Orton’s biographer John Lahr once said the playwright had willed himself into the role of the rebel outcast, and Leonie agrees with that. “He was creating the whole persona of Joe Orton,” she says, “but there were two sides to him. There’s this person in the diaries who’s up for it and says, ‘Come on, take me on’, but then there’s the other side to Joe – he could be a very caring person. He had beautiful, I’d say impeccable, natural manners, and he was the only one that treated me with any amount of kindness.” That was one of the reasons Joe’s death was so devastating for Leonie: she lost the only man who cared about her.

In her book, Leonie gives us some of the details of the relationship with her brother as well as some of the gruesome minutiae of their childhood. They were brought up on the Saffron Lane council estate in Leicester in the 1940s and 1950s in a house run by their domineering mother Elsie. Elsie was crude, brazen and violent – she would hit her children with anything she could lay her hands on – but Leonie also thinks that it was from Elsie that Joe got his sense of the ridiculous. She remembers Joe secretly recording their mother’s conversations as inspiration for his plays, and she says that Kath, the fading, middle-aged landlady in Entertaining Mr Sloane with all her faux pretensions, was their mother turned into fiction.

Living with the real Elsie Orton was another matter though, says Leonie. “Oh, if you’d met my mother, she’s enough to turn any man off women, I should think,” she says. “She certainly scared me and she never showed us any love or encouragement in any shape or form.” Leonie says that when Elsie died, neither she nor Joe cried, and whenever Leonie was required to show some emotional reaction, she faked it. “I think we had this sense of detachment from our parents,” she says. “That’s what makes Joe a brilliant writer: the detachment. He doesn’t get emotional about things.”

Leonie also believes her brother really hit his creative stride after he was sent (with Halliwell) to prison for six months for defacing hundreds of library books. Their crime was to glue new cover blurbs onto the books which were much funnier and more outrageous than the originals and fooled readers into thinking they were the real thing. Take this one on a Dorothy L Sayers novel: “Read this behind closed doors and have a good s**t while you are reading it.” Somewhere in there is the beginning of Ortonesque.

Leonie is convinced the time her brother spent in prison was the imaginative and satirical blast he needed. “He was locked up for 23 hours out of 24 and he had some sort of revelation,” she says. “He found that he didn’t really care any more about what people thought about him. He just thought: f*** it, let’s do it.” Orton also said himself that prison sharpened thoughts about British society that were already emerging in his work. “Prison crystallised it,” he said. “The old whore society really lifted up her skirts and the stench was pretty foul.”

Within days of his release, Orton was firing like never before, converting a novel into his dark and frightening play Ruffian On The Stair and embarking on Entertaining Mr Sloane. But looking back, his release from prison and the success that followed was also the beginning of the path that led to his murder. Orton was discovering his talent, finding his voice and becoming a literary star, while Halliwell was going nowhere and starting to resent it. He felt sidelined and forgotten, dismissed by the couple’s new friends, sometimes to his face. One of them called Halliwell a middle-aged nonentity, precisely at the time that everyone was cheering at Joe Orton’s success. Halliwell couldn’t take it and after several years of moaning, carping and whinging, he snapped.

So the obvious question is: what on earth did Joe Orton see in Halliwell? The couple met at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in the early 1950s when they were training at actors and, on the face of it, had little in common. Halliwell was a balding, morose, middle-class mummy’s boy with a childhood just as dark as Orton’s, but in a different way. When he was 11 years old, a wasp stung his mother on the tongue and she died within seconds right in front of him. Seven years later, Halliwell found his father with his head in the oven. He stepped over the body, put on the kettle, made a cup of tea and then went next door to tell the neighbours that his father was dead. Halliwell also wanted to be a famous and successful writer. But only Orton achieved it.

Leonie thinks the relationship between Halliwell and her brother lasted so long – they were together for 15 years – because at some level Joe needed Kenneth – not sexually, but intellectually. “I have spoken over the years to the few people who had met Halliwell – I met him several times – and I have never heard one person say anything nice about him,” she says. “There was nothing endearing about Kenneth. But the point is that Joe really respected his intellect. Ken was a brilliant editor and his input was really well respected by Joe, even though towards the end of the diaries it’s clear Joe was sick to the back teeth of him. Fancy coming home and your boyfriend has written across the wall, ‘Joe Orton is a spineless t**t’. I mean you wouldn’t put up with that, would you?”

Does that mean that Leonie thinks Joe was on the point of leaving Hallliwell? “That’s debatable,” she says. “Joe would have liked an amicable separation but it wasn’t going to happen, clearly. They were looking at houses in Brighton and they’d gone down there several times to look at different places and I think his idea was going to be that he could sort of ensconce Kenneth down in Brighton and have the flat in London and then visit him at weekends. But Halliwell wasn’t going to be buying into that.”

Leonie thinks one of the real problems towards the end was the fall from grace that Halliwell had to endure: from mentor and guide and a man who thought he was the one who was going to be the great writer to playing second fiddle to his famous boyfriend. Friends of the couple had also noticed that Halliwell was seriously mentally ill, although whether Joe had noticed is unclear.

“Yes, he was mentally ill,” says Leonie. “They were committing him to hospital the next day. But I’ll tell you what I think: killing Joe was a bloody selfish act. In the end, he knew that he was losing this man and he wasn’t prepared to do that and if he couldn’t have him, nobody was going to have him. What Kenneth did was so selfish, so wicked.”

Could Leonie ever forgive him? “No, never. People say, ‘What about your soul?’ and crap like that. And I say: 'Well that’s easy if you believe in God but I’m an out and out atheist – why should I worry?' Over the years I’ve thought an awful lot about it, and I take on board that Kenneth was ill and life seemed dreadfully unfair – well, I’m, sorry my dear, life is dreadfully unfair. Kids say that from about four years old. Life isn’t fair. I despised Kenneth Halliwell and I still do.”

Leonie Orton is also still frustrated with Halliwell over the final mystery of her brother’s death and would like to know whether it was him that removed the pages which are missing from her brother’s diaries. Halliwell’s suicide note said: “If you read his diary all will be explained. P.S. Especially the latter part.” But there is no latter part. The diaries end abruptly on August 1, 1967, a full eight days before Joe’s death and Leonie says that simply doesn’t ring true.

“It’s useless to say that maybe there weren’t any missing pages,” she says. “I’ve been through the diaries and I’ve counted the days when Joe didn’t write anything and he never missed more than a day, a day and a half. There’s pages missing – sure as birds can fly there are missing pages.”

As to what happened to them, Leonie thinks there’s a possibility that, in his confused state, Halliwell destroyed the missing pages himself, although she also thinks there’s a possibility that Joe’s agent Peggy Ramsay did it to protect a famous person who may have been mentioned.

Another theory that Leonie has wondered about is whether the missing pages might contain details about an affair that Joe was having. Could Joe have been preparing to leave Halliwell for this man, and could this man still be alive? He would probably be in his 80s now, but Leonie still hopes that he exists and might come forward one day to tell her more about her brother’s last days. She is also hopeful, but realistic, about the chance of ever reading those missing pages. “I would lose my right arm to read them,” she says.

In the meantime, she has a few other projects in hand, including a new production of Loot at London's Park Theatre, which opens on August 17. She is also hopeful that an unedited version of Joe’s diaries, plus his juvenile diaries, will be published later this year.

The diaries are still one of the most important chronicles of gay life ever published and Leonie has lost count of the number of young gay men who have come up to her and said, ‘Let me shake the hand of the sister of Joe Orton’. “They say things like, ‘Until I read those diaries, I was really closeted – I didn’t come out to my parents, I didn’t come out to my workmates, some of my friends didn’t even know but reading the diaries, I thought, now I’m coming out’.”

Leonie also thinks the diaries, in a weird way, provide a template for how to run your life and relationship. Yes, Joe Orton’s life ended in blood, but most of the diaries are full of life, bravura and lots of fun and Leonie thinks there’s something to be learned from that. The first lesson is – don’t end up like Kenneth Halliwell, all bitter and regretful. “If you go and live with somebody,” says Leonie, “you’ve got to take them on and if it’s not good, then get the hell out.”

But Leonie Orton thinks that, even 50 years on, there’s still a lesson to be learned about sex: don’t be uptight for God’s sake, grasp the opportunity because it’s the only way to remain sane. “It’s like Joe says,” explains his sister. “You should have fun with your genitals while you’re young, because if you don’t, when you’re old you’ll regret it.”

Leonie Orton is at the Edinburgh Book Festival on August 22, at 2.30pm. For more information, see www.edbookfest.co.uk. I Had It In Me is published by Quirky Press at £12.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here