Berlin Alexanderplatz, Alfred Doblin, translated by Michael Hofmann Penguin Classics

£14.99

Review by Trevor Royle

IT IS a regrettable fact in the publishing world that some books get the reputation of being unpublishable. Either they are too long or too short or too prolix or simply reader-proof. James Joyce’s great novel Ulysses was one of that number yet when it achieved fame in the 1930s it attracted the unwelcome reputation of having more buyers than readers. To be seen with a copy was to mark the owner as one of the cognoscenti who were prepared to cock a snook at authority and to revel in the frisson that the novel might just be a little naughty, having been burned as obscene by the US postal authorities. Today it is regarded as one of the classics and younger generations probably wonder what all the fuss was about.

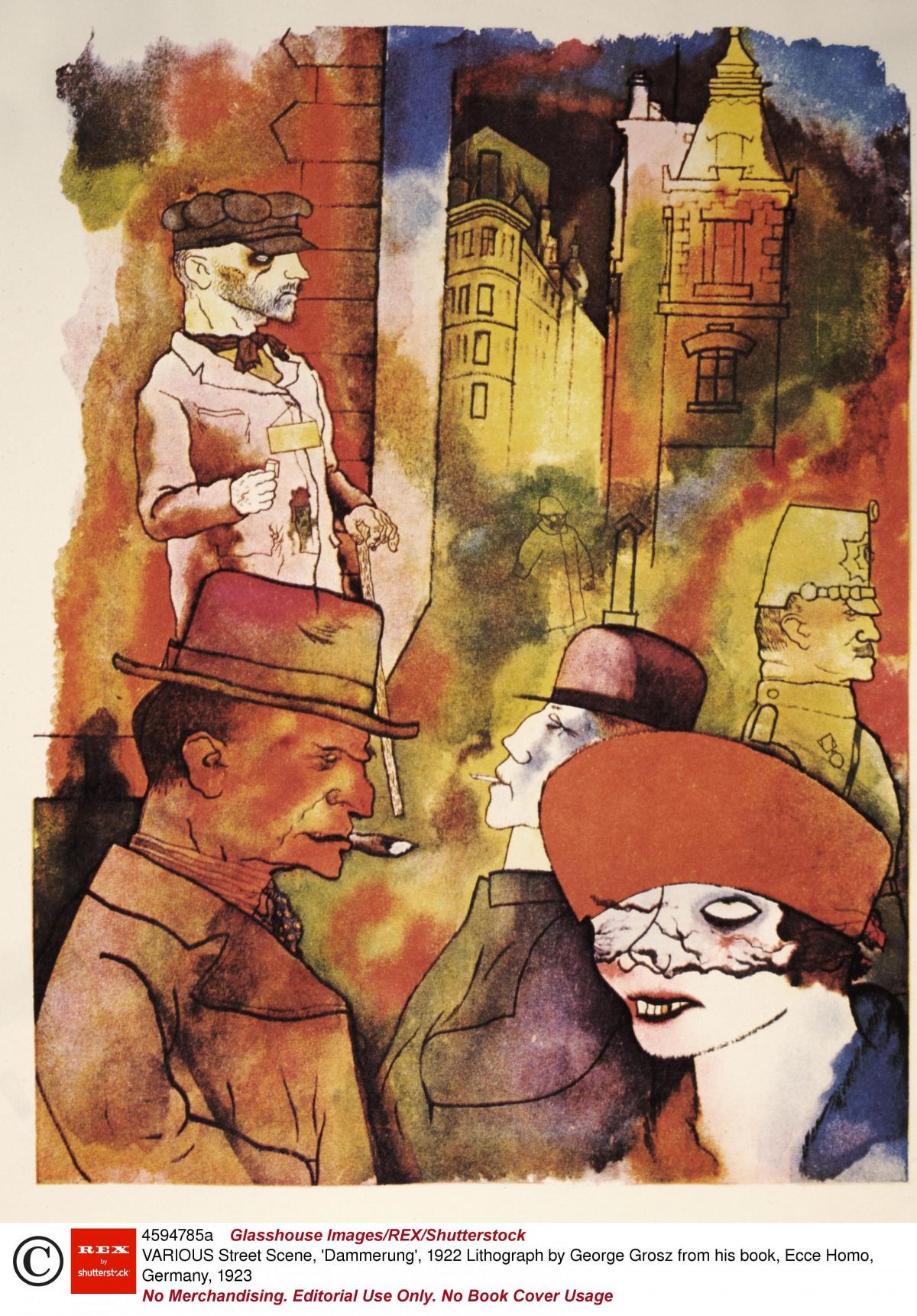

The same holds true for another novel from the same period with which Ulysses has often been lazily compared – Alfred Doblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz which was published in 1929 and steadily gained a reputation as “a must read” piece of fiction. The trouble was that not only was it written in German but as Doblin’s choice of language was the argot of Berlin in the 1920s it was pretty much untranslatable. Not that it could not be understood by any reader with a working knowledge of German but the rich patina of the language spoken by the main protagonists would be lost and Doblin’s masterpiece would be diminished as a result. Attempts were made to produce an English language version and the novel has even migrated to the cinema screen, most recently in 1980 when Rainer Werner Fassbinder created a 15-hour epic, but for the most part Doblin and his great novel remained on the outside looking in.

All that should change now with the appearance of Michael Hofmann’s latest translation which does full justice to the original text by embracing the weirdness of Doblin’s view of the city and the period just before the Nazis came to power. In a revealing Afterword Hofmann explains that his aim was to avoid leaving the reader “at sea in this bitty, yeasty collage” and to get to the heart of the matter. In other words, he set out to be true to Doblin’s original intention while at the same time addressing the sheer sense of surprise and innovation which infuses the narrative. Intriguingly he hints at the possibility of taking a leaf out of modern Scots orthography but wisely perhaps he has trusted his own voice.

The story is soon told. On the surface its main character Franz Biberkopf is a pretty unsavoury character, a pimp living in an underworld of crooks and spivs who is given to sudden uncontrollable rages – he murdered one of his girlfriends – yet longs to lead a solid and orderly life. When the novel opens he has just been released from Berlin’s Tegel Prison and Doblin takes him into the proletarian Alexanderplatz area of the city which he himself knew while working as a doctor and would-be author. It is a picaresque journey enlivened by the characters who swim into Biberkopf’s orbit and it quickly becomes clear that despite his bad behaviour he is not an unrequited sinner but a man struggling to find a sense of redemption, all the while clinging to a vague hope that things can only get better.

But in the chaotic environment he inhabits the opposite happens. Naively putting his trust in others Biberkopf finds himself involved in a succession of shabby deals, petty crimes and drunken escapades which culminate in yet another murder and an accident in which he loses an arm after being pushed from a car. For a moment it looks as if there is no escape from this cycle of violence and betrayal, but Doblin springs one last surprise. At the very moment that Biberkopf seems to be imploding he is offered employment in a small factory and that is that. “He accepts,” says Doblin/Hofmann. “Beyond that there is nothing to report on his life.”

If that sounds a grim outcome, on one level it is, but beyond the relentless prodigality the novel has been enriched by a collage of fleeting impressions of the bars and down-at-heel dance halls of the Alexanderplatz and by a rogues’ gallery of characters as rich as any created by Bertholt Brecht. Doblin died forgotten after the Second World War but his genius lives on in this wonderful translation which fully captures the melancholic and claustrophobic world of a city on the verge of being changed for ever by political forces beyond its control.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here