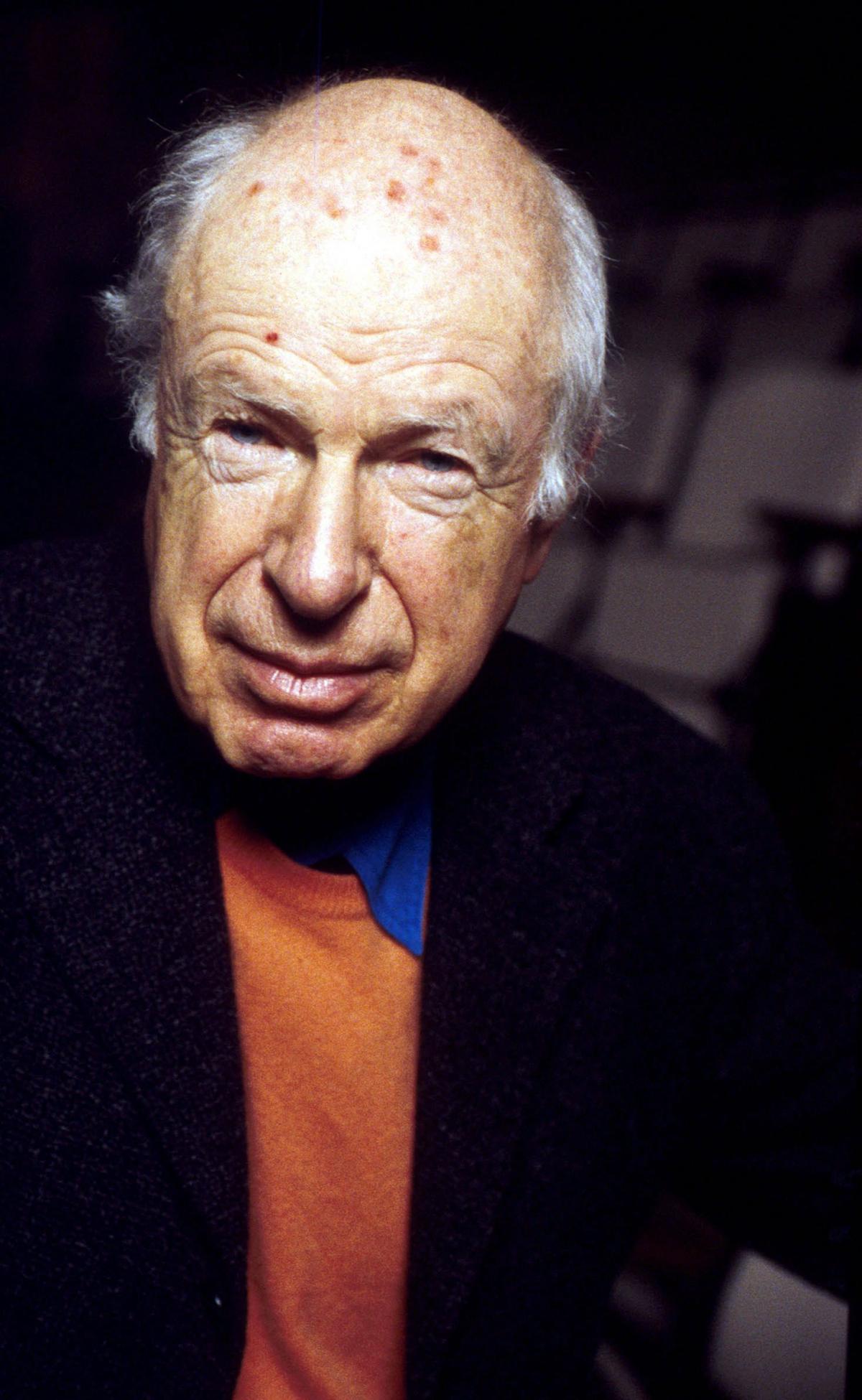

Peter Brook is no stranger to Scotland, ever since the guru of European and world theatre first brought his nine-hour epic, The Mahabharata, to Glasgow in 1988. That was at the city’s old transport museum, which by 1990 had become Tramway, the still-functioning permanent venue that opened up Glasgow and Scotland as a major channel for international theatre in a way that had previously only been on offer at Edinburgh International Festival.

Brook and his Paris-based Theatre des Bouffes du Nord company’s relationship with Tramway saw him bring his productions of La Tragedie de Carmen, La Tempete, Pellease et Mellisande, The Man Who…, and Oh Les Beaux Jours – the French version of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days – to Glasgow.

Thirty years on from The Mahabharata, Brook comes to EIF with another piece of pan-global theatre as part of a residency by Theatre des Bouffes du Nord, which Brook has led since he decamped to Paris from London in the early 1970s. The current Edinburgh residency has already seen Katie Mitchell and Alice Birch’s adaptation of Marguerite Duras’ novella, La Maladie de la Mort, and Robert Carson and William Christie’s reimagining of The Beggar’s Opera, staged here.

The Prisoner, co-written and co-directed with Brook’s long-term collaborator, Marie-Helene Estienne, is a new work that comes from a very real place.

“The Prisoner is a true story from forty years ago in Afghanistan,” says a now ninety-three-year-old Brook. “I saw a man who had been condemned to sit outside of a prison for his sentence, staring at it. The look in his eyes was so strong that up until now it’s stayed with me, and has made me question; who was he and what was he doing there? I never found out what this man had done and what his crime was but the look in this man’s eyes has stayed with me. I couldn’t leave this story, because it doesn't leave me.”

Brook and Estienne tried various means of bringing The Prisoner to life over the years, and it eventually found its form over the last year.

“With Marie-Hélène Estienne, and others, we made different moments as a film in one country and another,” Brook says, “but none of them really corresponded with what we thought the story demanded. About a year ago we decided that now was the moment for The Prisoner, and for the theatre, a story for the here and now.”

In this sense, The Prisoner’s portrayal of an incarcerated man chimes with much of what is going on in the world without ever being didactic.

“Since seeing the man in Afghanistan,” says Brook, “I have asked questions about who he was and what he was doing there. The Prisoner looks at these questions and the themes surrounding them, which relate to everyday aspects of our lives. It’s like a myth coming from a Greek tragedy, far away, but at the same time, it's a detailed story about our current situation.”

EIF’s French-tinged theatre programme this year is perhaps a quiet acknowledgement of the fiftieth anniversary of the political and cultural radicalism that erupted out of Paris in 1968. Beyond the Theatre des Bouffes du Nord residency, Unicorn Theatre and Untitled Projects have just opened Stewart Laing and Pamela Carter’s stage version of French enfant terrible Edouard Louis’ novel, The End of Eddy, while French choreographer Philippe Saire has already presented his family-friendly show, Hocus Pocus.

Back in week one of the Festival, Druid Theatre presented production of Samuel Beckett’s twentieth century classic Waiting for Godot, which was originally written in French by the Paris-exiled Irishman. Such internationalism is at the heart of Brook’s work.

“When starting the International Centre of Theatre Research out of the Bouffes du Nord, we wanted to show that it's possible to go through boundaries,” says Brook. “We made our groups international. People of different groups and languages coming together to work together. Audiences see that, and that’s what all theatre is about – being together.”

The Prisoner, Royal Lyceum Theatre, August 22-26, 7.30pm, August 25, 2.30pm.

www.eif.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here