Ken McNab

“You say you want a revolution…well, we all want to change the world.” Not for the first time, John Lennon’s cultural antennae proved to be a lightning rod for a world mired in social and political transition. Equally, not for the first time, the most maverick of the Beatles caught the prevailing mood of the times.

Revolution was Lennon’s musical dissertation on 1968, a year of violence and dread, and the first song the Beatles recorded for the follow-up to Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Vietnam War raged, civil rights protests and vicious backlashes proliferated across America, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy died at the hands of gun-wielding executioners, the hippie enclave at San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury had descended into a quagmire of hard drugs and crime, protesters and police clashed at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Student power flared at campuses as far field as Berkeley and Paris, Russian tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia, numerous countries were held in the stone fist of brutal dictatorships and the dry tinder of Northern Ireland politics sparked into mayhem.

And, on November 5 Richard Millhouse Nixon defeated Democratic rival Hubert Humphrey to become the 37th President of the United States and, unknowingly, Lennon’s future nemesis.

Only 17 months earlier, Lennon had proclaimed All You Need Is Love to build a better world. But the flowers that had blossomed in 1967’s Summer of Love had fast withered, replaced by a dystopia-tinged winter of discontent, from which even the Beatles could not escape. Sergeant Pepper, the band’s benign symbol of psychedelia, had been replaced by the marching sounds of street fighting men, epitomised by the Rolling Stones’ track of the same name.

This, then, was the backdrop to Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and George Harrison releasing their ninth album. The eponymously-titled The Beatles, a sprawling 30-track double album, was a quixotic quilt embracing almost every style of music from proto heavy metal, rock, pop and Calypso to bluegrass-tinged country, chamber music and even the musique concrete of avant-garde.

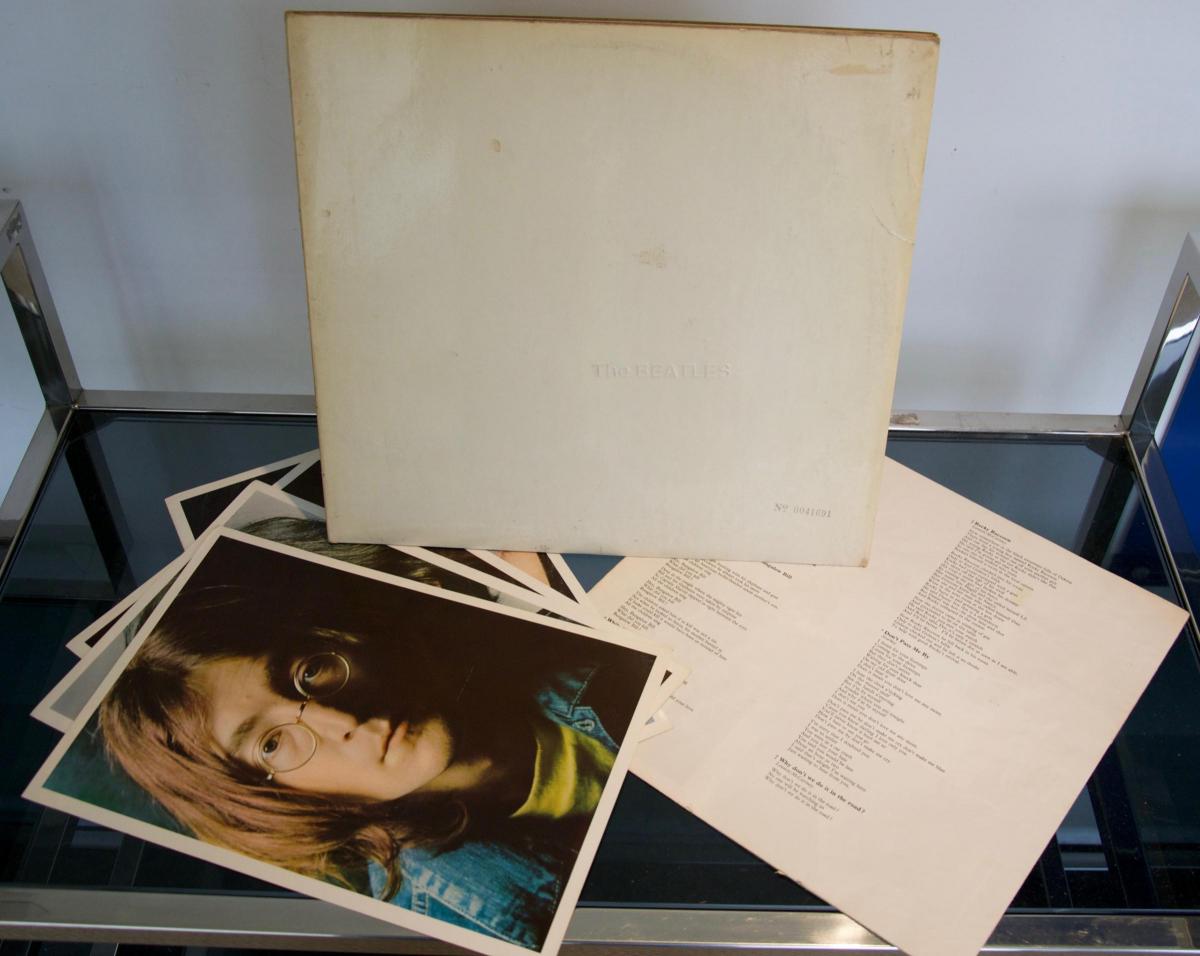

Released on November 22 – the fifth anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination – it was the most radical collection of songs the quartet assembled and as far removed from Pepper and the ill-fated Magical Mystery Tour project as could be imagined. Raw, often flawed, and frequently veiled in shadow.

Almost five months in the making, and nearly 94 minutes in length, it had no graphics or text on the white-bleached cover other than the band’s name embossed on its sleeve, pop art creativity that guaranteed it would be forever imprinted on public consciousness as simply The White album. It would go on to become their best selling album, certified at over 20 million units by the Recording Industry Association of America.

Between the grooves, however, lay the sound of four musicians entangled by personal and professional partitions, of a band chafing at the limitations each imposed on the other. The White Album is the start of The Beatles’ long goodbye, a farewell that had its trace echoes in the death of their manager and mentor Brian Epstein from a drug overdose in July 1967 and would ultimately culminate in the tatty tombstone of Let It Be.

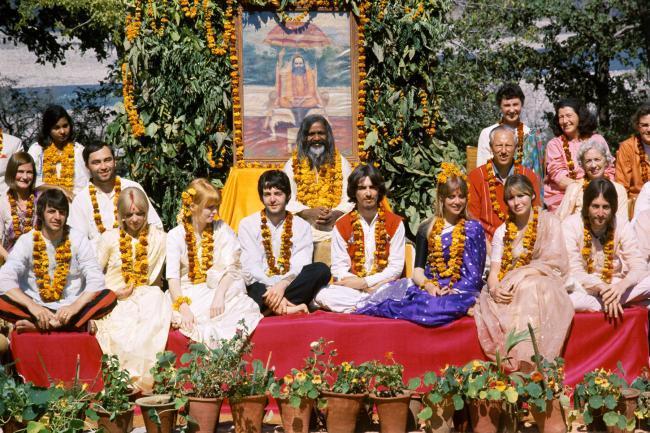

Yet the album’s roots lay in the bliss of their visit to India in February of 1968 to study Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, a chilled-out setting that inspired a huge outpouring of creativity, especially from Lennon and McCartney. Harrison often chided them when the guitars came out: “We’re here to meditate.” But the two Beatles would often meet clandestinely in each other’s rooms to review their new work. "Regardless of what I was supposed to be doing," Lennon later recalled, "I did write some of my best songs there.”

After returning to Britain all four Beatles gathered at Harrison's bungalow in Esher and banged out over 20 of the unvarnished acoustic demos that had been written at the ashrams in Rishikesh, a prodigious amount that of songs that, when added to others already in their bottom drawer, would only fit onto a double album.

The sessions proper began on May 30 in unorthodox fashion. Lennon, in the midst of a marriage break-up, arrived at Abbey Road studios with his new girlfriend, Yoko Ono, a Japanese avant-garde artist. Her malignant presence created an unwanted dynamic between Lennon and the other three who had always seen the studio as a (Northern) male-dominated sanctuary. Yoko began to make suggestions about their music – the ultimate taboo.

Hurt and not a little threatened by Yoko’s arrival in Lennon’s life, McCartney felt the need to get even. Revenge took the form of Francie Schwartz, an American writer, with whom he was having a rebound fling after his split from actress Jane Asher, who also began showing up at the sessions. And so began a bitter stand-off that would last throughout the rest of the recordings for The White Album and, indeed, the remainder of their days as a functioning band, leading to irrational accusations that Ono was to blame for their eventual split in April 1970.

Soon, the contentment of Rishikesh was replaced by conflict between all four Beatles. Without Epstein’s calm guidance, they were untethered. Lennon and McCartney no longer sat eyeball to eyeball to turn base metal into precious musical gold. Rather, each one brought their own fully-formed songs into the studio and sang lead, with the other three reduced to the roles of pliable session men during takes. And this was, largely, the pattern that was set in stone for the rest of the sessions that became The White Album.

Over the next five months, tensions that had always bubbled under the surface, erupted. The atmosphere in the studio occasionally turned toxic, fuelled further by Lennon starting to dabble in heroin. Harrison, the so-called Quiet Beatle, was finding his voice by penning his own, great songs and no longer felt under Lennon and McCartey’s autocratic yolk. Indeed, for the recording of While My Guitar Gently Weeps, he broke Beatle protocol by recruiting Eric Clapton to play the lead solo, a move that had the desired effect of putting the others on their best behaviour. McCartney recorded several tracks on his own, isolating Lennon, the man whose validation he craved most. Amidst all this rancour, it was the most amiable Beatle, drummer Starr, who was the first to walk away. He quit the band for a week in August, spending the days in quiet contemplation on Peter Sellers’ yacht in Sardinia, while McCartney filled in on the drums. Years later, he said: “I left because I felt two things: I felt I wasn't playing great, and I also felt that the other three were really happy and I was an outsider.”

The gloom also spread to other members of the Beatles’ inner sanctum. Engineer Geoff Emerick packed his bags after one verbally bruising encounter with Lennon. Producer George Martin, whose sure-footed instincts had been key to their success, felt himself being frozen out. Fed up with the growing hostility, he abruptly went on holiday without a word, leaving them largely to their own devices in the studio to cause chaos. Others, however, such as engineer Ken Scott, recall moments when the magic of all four Beatles perfectly coalesced.

Amazingly, though, out off all this friction was born an album that defied expectations, certainly from those who witnessed at first hand the turmoil in the studio. Somehow, all the loose threads were woven together to form a masterful tapestry. The White Album emerged as a colossal accomplishment.

The fact that the Beatles were able to deliver such a shimmering, voluminous record under the circumstances is a testament to their incredible talents, both as a group and as individuals. McCartney’s contributions notably include Back In The USSR, Ob-la-di-ob-la-da, Helter Skelter, the song hijacked as a rationale for murder by Charles Manson and his followers, and the ethereal Blackbird, an endorsement of the growing Civil Rights movement in America; Lennon delivered some of his best work, including Dear Prudence, Happiness Is A Warm Gun, Sexy Sadie, his venomous putdown of the Maharishi, and Julia, the heartending tribute to the mother he lost when he was 18. (But he also produced Revolution Number Nine, the Yoko-influenced avant-garde track derided by the NME as “a pretentious example of idiotic immaturity”); Harrison’s songwriting development gained further traction with While My Guitar Gently Weeps as well as Long Long Long, a song that combined the writer’s spiritual quest for inner peace and signposted All Things Must Pass, his first solo album; Ringo played the drums as well as contributing his one and only solo Beatles song, the largely forgettable Don’t Pass Me By.

During the sessions, the prolific McCartney also delivered Hey Jude. But such was the bounty they had already created, there was no need to consider adding the song that became their biggest-selling single to the album. With hindsight, it’s inclusion would have raised the album’s bar even higher.

Immediate reviews for the White Album were, however, mixed. Tony Palmer, writing in The Observer, wrote: “If there is still any doubt that Lennon and McCartney are the greatest songwriters since Schubert, then the album The Beatles should surely see the last vestiges of cultural snobbery and bourgeois prejudice swept away in a deluge of joyful music making.” In contrast, Nik Cohn’s coruscating verdict in The New York Times considered the album “boring beyond belief” and described more than half the songs as “profound mediocrities”.

And therein lies one of the most enduring arguments about the record. Should it have been a single album, with some of the dead wood carved away? George Martin thought so as did Ringo Starr; Lennon rated it his favourite Beatles album. Half a century on McCartney remains a fan of the four-sided disc, declaring: “It’s the bloody Beatles White Album, it sold, shut up.”

Ubiquity has been kind to album, despite the faultlines that marked it out more as the work of four individuals than a proper group album like Revolver. Listening to it today, it retains an ageless freshness, the flaws somehow adding another layer of imperfect charm to the sprawl.

Next month, on November 7, a 50th anniversary version of the record, remastered by Martin’s son Giles, will be released by Apple, the Beatles company, and will include for the first time the campfire-like demos recorded at Harrison’s house, the Holy Grail of bootlegs for many fans. Opening up a new listening experience for those who bought it the first time and those who perhaps might hear the Beatles once again reinventing themselves.

It’s never been as revered as the golden run from Rubber Soul, Revolver through to Pepper, yet some of the album’s songs remain among their best work.

On its release in 1968, the White Album captured the world’s biggest band at a crossroads, politically and socially. Five decades on, globally speaking, the more things change the more they stay the same. And here once again we have the sounds of the Beatles White Album, frozen in rock ’n’ roll amber but with the patina scrubbed clean and buffed to a new degree of excellence. And resurrected for a new audience perhaps looking to start their own revolution.

Ken McNab is the author of The Beatles in Scotland and In The End, The Last Days Of The Beatles, to be published next year by Birlinn Polygon

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here