“SORRY, I’ve got somebody wanting a picture.”

Darcey Bussell has just been spotted. She’s in the street in London, mobile phone stuck to her ear, talking to a journalist (that will be me), aware that she has a train to catch and also now accosted by a couple of teenagers.

“Someone wants to know what shoes I’m wearing,” she tells me before breaking off to talk to them. “I think they’re called Atlantic Stars,” she says to them. “I think I bought them here. Yes. I did.”

The picture is taken, the trainer brand duly noted, and her accosters go away happy.

She apologises to me once more. “Sorry.”

That’s the price of fame, Darcey, I suggest. That’s the price of being a Saturday night prime time star. “No, no, no. They’re foreign students. They have no idea. They just really like my trainers.”

It’s difficult to believe that anyone wouldn’t recognise Bussell in this, the age of Strictly Come Dancing. Even for those X Factor fans among you, never mind those of us who spend our Saturday night hoovering up the Dad’s Army reruns on BBC2, the ubiquity of Strictly is impossible to escape, helped out this season (as it is most seasons to be fair) by some off-duty canoodling. Or should that be can(n)oodling?

Not that Bussell is going to go there. She’s way too in control of things for that. Plus, her default setting is positivity anyway.

As one of Strictly’s judges, Bussell is the voice of reason. She’s the former ballerina who brings sober enthusiasm to offset Craig Revel Horwood’s panto villain act and Bruno Tonioli’s fizzy-pop-and-birthday-cake effusions.

That said, she can do effusive when it comes to Strictly. “It’s been going for what? 15 years? And I hope it goes another 10, because it affects people in such a good way.”

She pauses for a moment and then adds, “even with the crazy publicity.”

There you go. She knows that the water cooler talk hasn’t been strictly about the dancing. How could she not? But she won’t go any further.

And, to be fair, there are other things to talk about. The thing is, you could easily say that of all the things Bussell has done in her dance career Strictly is merely the most visible.

She has been a ballerina, has danced the lead in Swan Lake for the Royal Ballet, been a guest dancer with the Kirov Ballet and at La Scala. This is the Darcey Bussell I am most interested in. The young woman who took her love of dance and turned it into a career, an art, who pushed herself to extremes in the name of ballet.

It’s possible that slightly gets overlooked now. She is in a new phase after all. As well as Strictly, she has also made documentaries about Hollywood musicals, Audrey Hepburn and, most recently, dance and mental health (you’ll have to wait for that one to be screened). Married to Australian businessman Angus Forbes, she is also a mother to two teenage girls Phoebe and Zoe. Oh, and she is a dame as well.

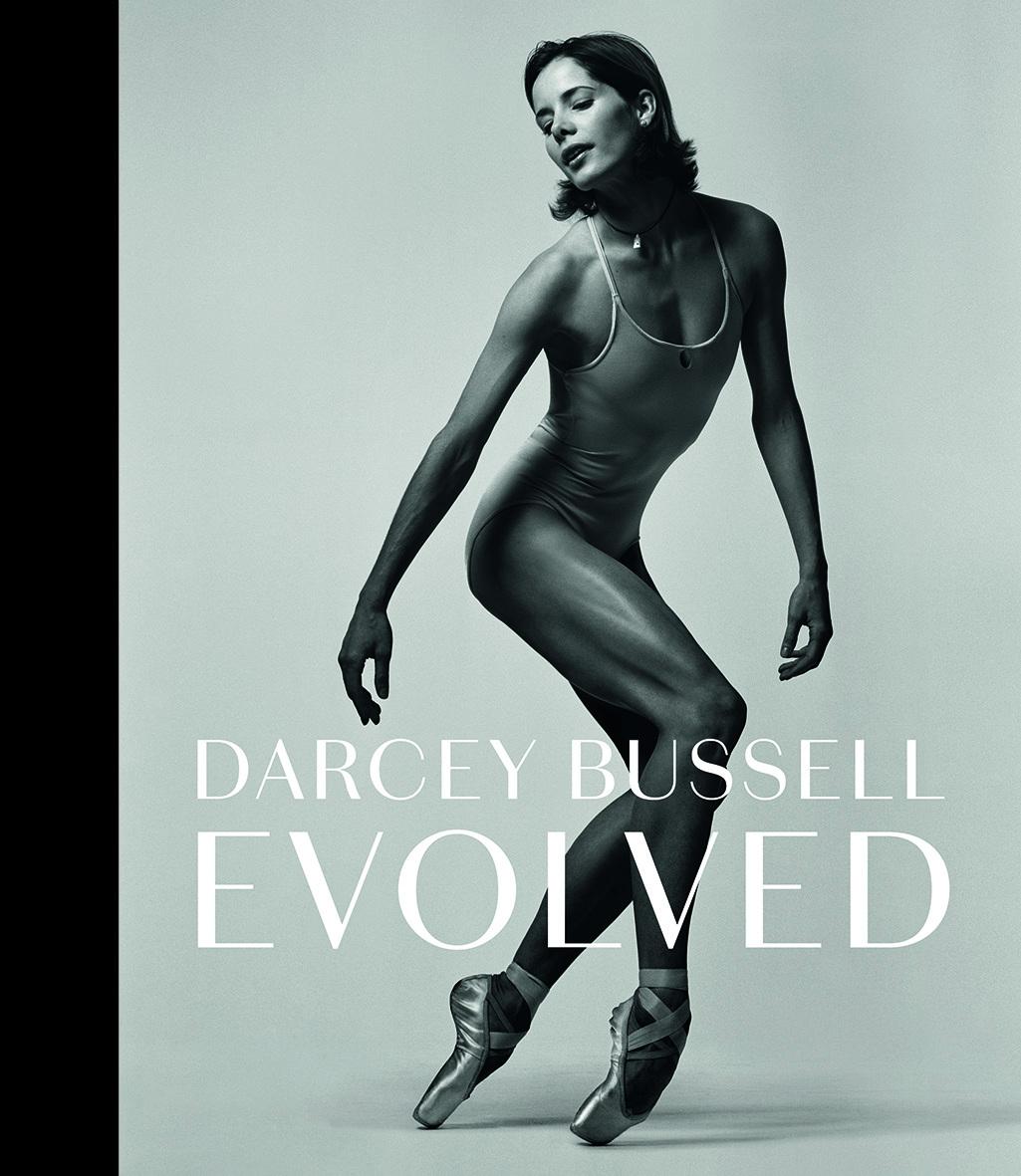

But the reason we are talking is down to the fact that she is the subject of a new book, Evolved, published to tie in with her 50th birthday (which is a little previous as she doesn’t reach her sixth decade until next spring).

The book is a handsome gather-up of photographs taken at all the stages of her career. Here are rehearsal shots, advertising posters, fashion shoots taken by photographers ranging from Arthur Elgort to Annie Liebovitz, Mario Testino to Richard Avedon.

The result is photographs of Bussell en pointe in a capsule in the London Eye or dressed in red at the top of the Albert Memorial. Here she is in tutu and ballet pumps, in Doc Martens, in leather jumpsuits (can’t imagine why anyone would be interested in that) and practicing for her part in the 2012 Olympics closing ceremony. Here, in short, is the dancer she once was.

It is also, in passing, something of a visual biography. The public view of the dancer; The posters, the ads, the “theatre” of being in the arts as she calls it.

And in the gaps, you get a glimpse of the young woman she was, her determination and her joy of dancing.

There’s a Gap advert taken by Annie Liebovitz in the book, I say, in which Bussell looks unfeasibly young. In her teens maybe? “I’m not in my teens,” she says, putting me right.

Well, Darcey, do you recognise that young woman? “I do. That is still me. I look a bit shy and not as confident, but that’s me through and through.”

Bussell’s story starts in the 1960s and maybe at the beginning it is a very sixties story. She was born in 1969 and given the name Marnie Mercedes Darcey Pemberton Crittle. Her mum Andrea was a former model, her dad John was an Australian fashion designer whose clients included the Beatles and Princess Margaret.

But her parents divorced when she was just three and Bussell was later adopted by her stepfather Philip Bussell. Her father was not a figure in her life.

By five Bussell was taking dancing lessons. She enrolled at the Royal Ballet Lower School at the age of 13. She joined Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet at 18 and became the youngest principal dancer in the Royal Ballet School two years later.

Dance was something of an escape. She was bullied at school. That and dyslexia made her school days miserable. “It had a big impact on me. It didn’t give me a lot of choices. So, I was lucky that dance came along.”

At the beginning, Bussell says, she just enjoyed dance. But it developed into a passion. “I think I got addicted to the disciplines and the boundaries it gave you. But it made you then be incredibly powerful with them. So, it enhanced confidence within me, which is really strange.

“In my first year when I joined the resident company it was a massive growing up time in my life. I was working very hard, learning new works constantly and I just suddenly felt in exactly the right place and I knew I was doing the job I was always meant to do, and I think I felt incredibly privileged to know that at such a young age, at 19, 20.”

Some of us are still trying to work that stuff out in our fifties, Darcey.

She laughs. “I had this great ambition and I was given the tools to do it.”

Unsurprisingly, Bussell is a huge advocate for dance in everybody’s life. It’s a positive force, she feels. She starts telling me about the BBC2 documentary she has been making about mental health and dance, about how dance is being used as a strategy to manage mental health, “to help people giving them a tool to make them understand their ups and downs and how they can control it and how it helps them express themselves in different ways and understand themselves.”

The truth is, she says, dance has such a weight to it. “It’s not this piece of lightweight entertainment that makes people gossip or gasp with delight.”

Thinking back to that bullied child she was, presumably dance has had a role in her own mental health story. “Yes, very much. And I have two teenage daughters of my own and realising how do you create some kind of balance in their lives with peer pressure and social media and everything that is thrown at them.”

Dance, she adds, isn’t just about elite performance. It can be part of all of our lives and we can benefit from it. “We always used to use it socially and it sort of disappeared from society. I think there is still a massive need for that and we shouldn’t rule it out and it should be part of people’s lives each week.”

I don’t think she’s talking about sitting down to watch Strictly here, I’m afraid.

Of course, in her case dancing was the life. We are talking about a dancer who was operating at the limits of her abilities. “Well, as a profession it is an extreme. When I talk about dancing in everybody’s lives it’s never to the extreme.”

The question is, how far did she push herself. What did she suffer? “As professional dancers you have a lot more knowledge abut how we can look after our bodies and how we can help ourselves and maintain healthier bodies.”

Well, were you dancing through pain? “Weirdly as a pro the pain is never as bad as if I was an everyday individual experiencing it for the first time. Like everything, you get used to it. It’s just a state of mind, being able to control that.”

Bussell made her farewell appearance at the Royal Ballet at the age of 38 in 2007. I wonder, does she miss being at her peak?

“No, I don’t miss that at all. I miss the people I worked with. I miss that collaboration with artists, creating something.

“That’s why I love being on Strictly because we are creating something very special and everybody’s there for the right goal and it’s very exciting.

“I don’t miss the physical pressure that I put my body under. It was a great time and I loved every minute of it, but, fortunately I keep my body moving, keep it supple and strong but I don’t have to do it as a living.”

And our bodies change over time, of course, I start saying. “But it doesn’t have to change, that’s the whole problem,” she says with an audible vehemence. “Why do you have to stop dancing? Why do you have to stop being physical just because you’re ageing? It’s a balance. You just don’t do it to extreme. You can’t dance all night, you know.”

When was the last time you danced all night, Darcey? “I’m disappointed. I can’t remember. How sad is that?”

The point I was going to make was that sometimes our bodies are not under our control. Illness, injuries, even pregnancy, changes things. Bussell’s older daughter Phoebe was born four months premature. Bussell suffered from pre-eclampsia and she was given an emergency Caesarean.

But she doesn’t see any negatives here when I bring it up. “I suppose you respect your own body more when you see it change. It’s changing for a good reason if you’re going to have a child. And it’s then about getting back into shape and believing that you can still be the same person.

“I think a lot of people don’t believe they are ever going to be the same person that they were in their twenties.”

She doesn’t agree. “If anything, they’ll probably be stronger in their forties than they were in their twenties.”

More than that, she says: “I think understanding your physical strength is also understanding your mental strength as well. They always say: ‘Healthy body, healthy mind.’ And so, if you know how far you can push your body you know yourself very well because of the disciplines behind it to achieve it in the first place.

“You find out so much about yourself as a dancer and I think anybody that experiences a tiny bit of dance will get a sense of that.”

These days Bussell keeps herself fit by dancing. Did you ever think otherwise? “I’m not a gym bunny,” she tells me with some emphasis. In other words, the Atlantic Star trainers are for show.

She does dance fitness to keep fit, she tells me, a routine “that gives you a flavour of every culture from around the world; some Arabic, Japanese, Flamenco even 1970s disco. As long as there is variety I’m happy.”

All those tendon-stretching years must have had an impact though. What was the damage done? Dodgy knees?

“There’s more than just dodgy knees,” she says. Well, yes. She’s had two operations on her ankles and reconstructive knee ligament surgery over the years. “But that’s the extreme of the art, so, no regrets.”

“Am I damaged goods? Definitely not. I’ve been empowered by my injuries.”

DARCEY BUSSELL: EVOLVED, published by Hardie Grant is out now, priced £30.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here