Behind the soup cans, the brightly-coloured Marilyns, the robotic men, the tear-stained faces, it was the machines that ran Pop Art. Or so you might infer from this new exhibition, dedicated to two of mid-century art’s most well-known names – one rather more so now than the other – and the mechanical ties that bound them.

“I’d been looking at ways to open out our Artist Rooms collection of Andy Warhol material,” says Keith Hartley, Deputy Director of the National Galleries and Chief Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art when we speak a week before the opening of the new exhibition devoted to the work of Eduardo Paolozzi and Andy Warhol. When he discovered, whilst reading, that Paolozzi and Warhol had exhibited together in June 1968 at the famous Four Seasons Restaurant in New York, in an exhibition programme of five young artists from America and Europe put together by the Art Advisory Service of the Museum of Modern Art, the pieces began to fall into place. “Paolozzi had this amazing career in the 1960s, about the time he exhibited in New York with Warhol. It seemed the right time to bring them back together.”

Whilst Paolozzi and Warhol worked on opposite sides of the Atlantic, they were both fascinated by the advent of the mass consumerisation of the post war years. But the link, says Hartley, who frequently met Paolozzi on the sculptor’s trips up to Edinburgh to discuss his sculptural gift to the Galleries, is more conceptual than visual.

Despite their shared interest in popular culture, in magazines, in adverts, what is of crucial interest is that they both discovered what they could do with screen printing at the same time in the early 1960s. “To Warhol, screen printing was a revelation, because it meant that he could make works of art which almost made themselves in a mechanical sort of way,” says Hartley. “Nearly all of his work was based on photography, and up to that time he’d been tracing a lot of images from photos, particularly from publications like Life magazine. When he found he could use photography directly in the screen printing process, he said that he could hand it over to almost anyone to do it, once he’d made the decision about images and colours. That’s what I like, he famously said. I want to be a machine.” Warhol’s camera was his primary machine – screen printing became another mechanical layer in the process of putting a screen between him and the rest of the world.

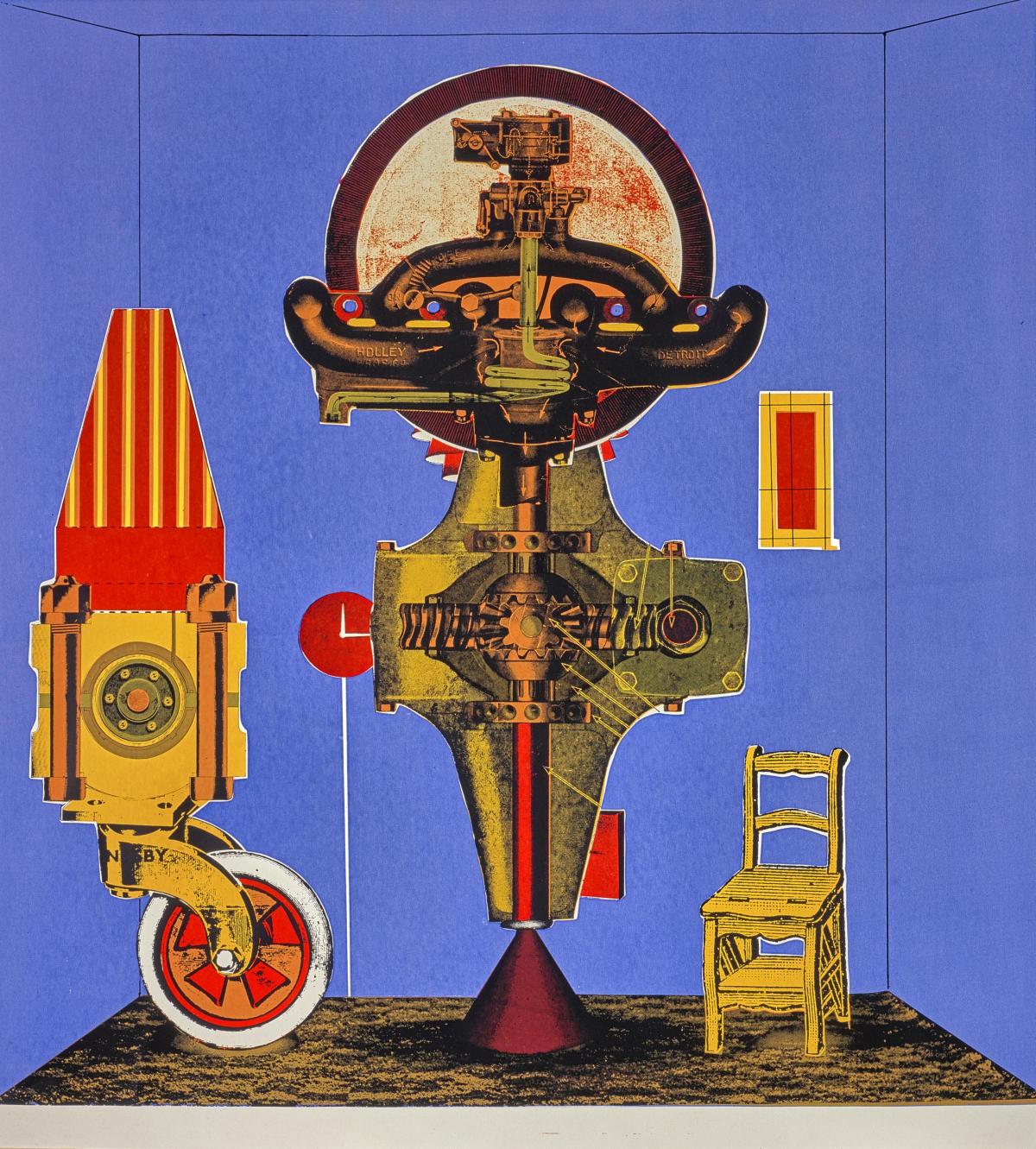

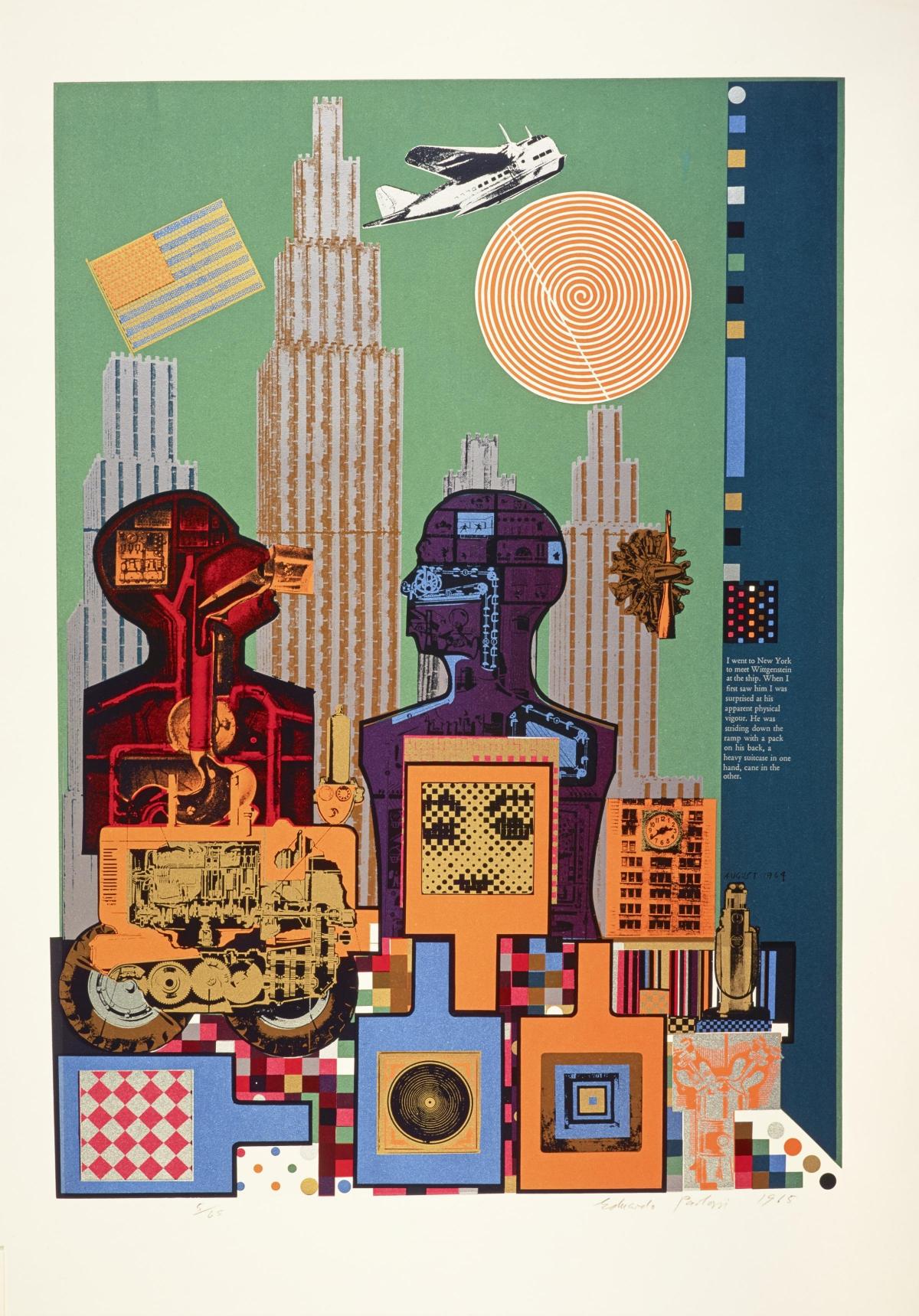

Paolozzi came to screen printing through master printer Chris Prater in London. “Instead of just doing collages all the time, he could photograph them and he could make prints out of them, he could actually colour each particular print of an edition differently. He did that with Metallization of a Dream in 1963. All 40 impressions of that print, he coloured differently. Warhol did something similar in 1968 with his Marilyn pictures, exhibited at the Four Seasons.”

Both sets of prints are key exhibits in the exhibition, the iconic Marilyns on loan from the Tate, the Metallization part of the National Galleries’ own superb Paolozzi collection. The exhibition, which Hartley has co-curated with SNGMA colleague Lauren Logan, is spread over four rooms with each artist taking up two rooms in a display showing the evolution of their art, deliberately curated to enable comparison between the two. There are key works from the famous 1952 lecture given by Paolozzi at London’s ICA, where he is credited with kickstarting Pop Art. There are screenprints and collages from the artists’ early and later careers. Amidst it all, the interest in popular culture, the obsession with new technology.

Warhol’s fascination was rooted in the Bauhaus interest in the increasing mechanisation of the relationship between the machine and art in Weimar Germany. For Paolozzi it was not just the machine, but the interface between man and machine. “It was a concern of his from a very young age right up until the end of his life,” says Hartley, who recalls Paolozzi going to the Wonderland toyshop on Lothian Road on every trip to Edinburgh, always emerging with something new, frequently mechanical. “He loved his ideas of the man machine, imagining that perhaps we would become machines. Now you see children of five going around with their mobile phones, almost as if it’s part of them.”

Paolozzi recognized this very negative side to human interaction with the machine, not least through the terrifying mechanisation and dehumanisation of the Vietnam war. Warhol, conversely, “was more interested in how the machine could enhance his art,” says Hartley. And it was the change in the ways of looking, so rapid in the 1960s, that was part of the mechanically-aided legacy of both of these artists.

Andy Warhol and Eduardo Paolozzi: I Want to be a Machine, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two), 73 Belford Road, Edinburgh, 0131 624 6200, www.nationalgalleries.org 17 Nov – 2 Jun 2019

DON'T MISS: Emma Hart: BANGER, Fruitmarket Gallery, 45 Market Street, Edinburgh, 0131 225 2383, www.fruitmarket.co.uk Until 3 Feb 2019, Mon - Sun, 11am - 6pm

Supersized jug-pot heads, tessellated windscreens and an ominous ceiling fan made out of cutlery. This is the work of Emma Hart, a photographer turned sculptor whose striking, thought-provoking and frequently witty ceramics won the Max Mara Art Prize for Women in 2016. This is her first Scottish show at the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh, full of new work created especially for the space and a re-hanging of her extraordinary 2016 prize work.

CRITIC'S CHOICE:

Just a few weeks now ‘til Collective Gallery draws back the curtain on its much-anticipated refurbishment of the William Playfair City Observatory complex on top of Calton Hill. Decades of dereliction with only the tread of a few committed amateur astronomers to disturb the wilderness growing up amongst the abandoned domes will soon be a distant memory.

But you can sneak your head over the stone parapet in some small way, now, for alongside the two new exhibitions which will open at the end of this month is “Collective Matter”, a collaboration with Design curators, Panel, an artist-oriented take on a gallery souvenir shop. “Contradicting the common structures of mass production and consumption usually associated with the Gallery or Museum shop,” they say, it will be wildly different from what you’d find in the tourist shops blaring out bagpipe reels on the Royal Mile below, wildly more expensive too, although for those of us whose pockets have more holes than receptive recesses it will also contain souvenir pencils and the like.

At the core is the fact that Collective know that many of the people mounting this hill will be here not just to see the art, not even, perhaps, but to see the buildings, to take in the history and the place. Collective Matter is a series of artist commissions reinterpreting the idea of the souvenir.

There are “postcards” here, the hill’s monuments reimagined by photographer Alan Dimmick, pegged on to the whisper-thin constructs of Danish mobile experts Flensted in a design collaboration that reveals the grit behind the architecture. Ceramicist Katy West reflects the secret “trades” history of the hill with a series of kitchen storage jars called Fair Play, whilst Rachel Adams has created a silver sextant and enamel Constellations necklace. Mick Peter’s scarf draws attention to women in astronomy, whilst Katie Schwab provides the practical, a Rain Poncho as colour-blocked circular marvel of waxed cotton that doubles up as a picnic blanket, inspired by the dyers cloths hung out to dry on the hill a century ago.

Collective Matter, Collective Gallery, City Observatory and City Dome, 38 Calton Hill, 0131 556 1264 shop.collective-edinburgh.art Opening 24th November (pre-order online) Daily, 10am – 4pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here