“That summer, mom ran away with Ollie Jackson (known on the football field as ‘Action Jackson’), Dad’s best friend …”

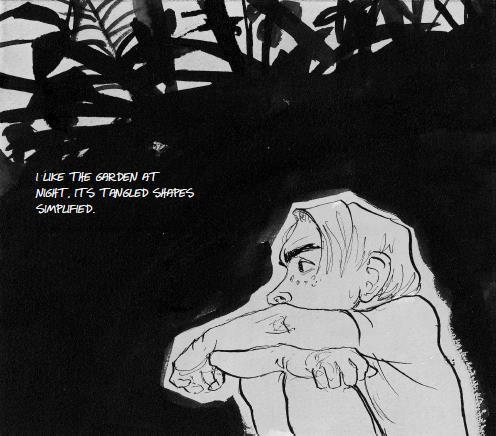

Adolescence is hard. Harder when your parents split up and you are forced to live in a new place where you know no one. That’s what happens to Russell Pruitt, the protagonist of David Small’s new graphic novel Home After Dark.

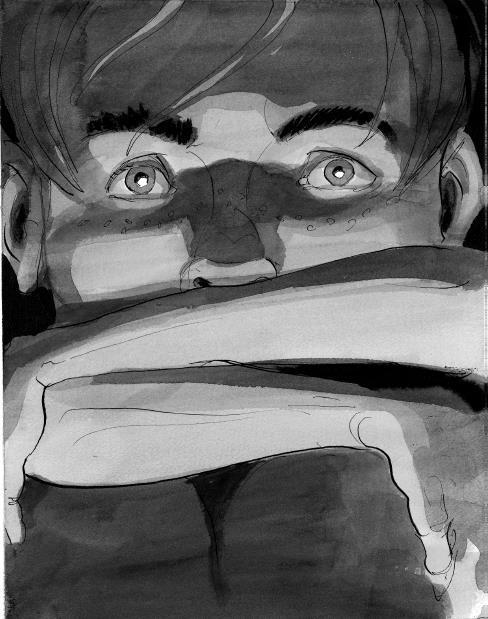

Vividly told in pencil and wash, Small’s story takes in bullying, burgeoning sexuality and animal cruelty. The result is a potent, disturbing graphic novel that has already drawn comparisons to Lord of the Flies and Catcher in the Rye.

Here, Small talks about the personal inspiration behind the novel, his visual influences and why he really doesn’t have it in for pets.

David Small © Gordon Trice

Can you trace back Home After Dark to the original idea? Does a story start with characters, a memory, a landscape?

Home began with a memory, not one of my own, but eventually moved on to include my own memories almost exclusively.

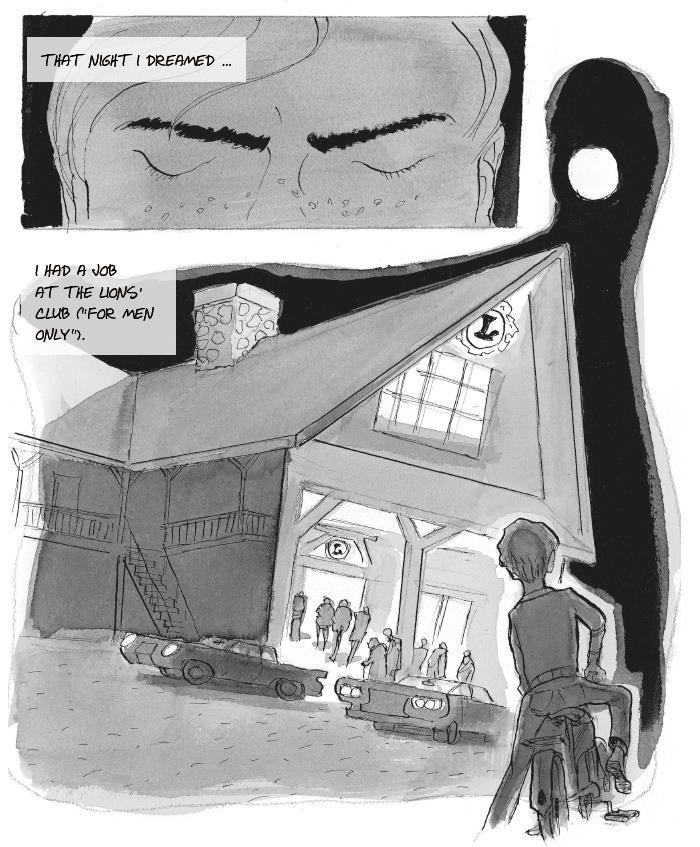

A close friend of 25 years – a man my own age who happens to be great raconteur -- was telling me stories about his adolescence in the 1950s in then-rural Marin County, California. I grew up in urban Detroit, Michigan, a much different climate and environment, but there was a lot for me to relate to, in terms of the 1950s: the clothes, the music, what was on TV, the cars and in my relations with certain male peers.

His stories centred around one bucolic summer spent with two buddies – all of them 13, all of them free of parental influence. They built a tree fort in the woods and, there, did 13-year-old guy things, smoking, drinking and speculating endlessly about sex. They played games in a junk-filled gully and made frequent forays to the local soda joint out on the highway, watching the older teens, to see what lay in their future. To me, all of this had a kind of legendary Huck Finn quality to it, so different from my own strangled adolescence.

Part of me still wanted to have been that boy having those kinds of experiences, so I listened with a kind of sadness tinged with envy. But, when a little psychopath entered the story, my ears perked up like a dog’s because ... well… who isn’t interested in psychopaths?

In Mike’s small town there was a kid -– call him Benny, a loner and a school drop-out — who liked killing small animals in macabre ways. Benny used to hang around the edges of Mike’s group, apparently wanting to get in. So, one day, when he approached them directly, one of them beat the crap out of him.

End of Mike’s story, except for the fact that he wondered about it for the rest of his life. Had the beating changed Benny? (Probably not.) Would he ever run into Benny again? (He hoped not.) Would Benny end up in jail or maybe in high political office? (You find these characters everywhere, yeh?)

I thought all of this was the basis for a good graphic novel, with a theme like “Sylvan Summer Interrupted by Gruesome Events.” Something on that order. It wasn't much of story as it stood then, but I thought things would develop. So, with Mike’s full permission and cooperation, I started making drawings.

Soon there was an outline and a stack of art which I sent off to New York. My agent and my editor could feel the energy in it and, soon, with a contract, I was out of the starting gate and going down the track.

All of this went splendidly, until it didn’t. About three months in, my editor said: “You’re imitating your friend’s voice and it doesn’t sound authentic. It doesn’t have any heart.” I knew this was true but, what to do about it?

For a couple of months, then, I hunkered down. I’ve been making and writing books a long time, so I don’t call these periods “writer’s block,” but, more a kind of crouch, waiting for an opening, for some light to come back in.

How quickly did you find the voice you needed to make it?

It came when I realised how resistant I was to using my own voice. That seemed a bit cowardly. Along with the conviction that using my own voice and my own experiences was absolutely the right thing to do, came the feeling that it was a logical next step.

Since I had already waded through the swamp of my childhood in my graphic autobiography Stitches, it seemed a natural progression to wallow around in the bog of my adolescence, to see what I could see. When I began to make those changes the book immediately got better. As the story became more personal it began to veer sharply away from my friend’s tales.

I changed the plot, eliminated several major scenes and cut out three major characters, including the psychopath Benny. The elaborate set-up for (and execution of) those animal killings had begun to distract from the arc of my story, which was the inner development of my protagonist Russell. I knew this would be much harder to illustrate but I had to do it.

Having said that, the book went through 12 complete revisions over the course of three years before it found its resolution. After the plot and the dialogues felt right, I looked at the art and judged it lacking.

That’s when I asked for a fifth extension of my deadline and took the whole 400 pages down to Mexico for 3 months. There, I redrew the whole thing, panel by panel, page by page on some Italian watercolour paper. Then my washes looked like silk and I was happy. Sort of. At any rate, it was time that I finally turned it in.

It’s clearly a troubling vision of adolescence. Is there anything good to be said of that period of our lives?

The absolute ignorance of who you really are or what you want to be, while at the same time you’re trying to develop the attitude, the arrogance, the affectation of independence necessary to help you break into adulthood, in retrospect it seems possibly the worst time of life. Future periods of abandonment, of illness, of real loss may affect us deeply, but there is no time like adolescence for the absolute uncertainty about how to proceed.

Someone asked me what I hoped readers might get from this book and I answered: “Company in the midst of adolescence, or in the memory of it.” No matter our gender, ethnicity or sexual bent, we all go through a version of the same chaos at that time of life. At least I think we do. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe some people sail blithely through it, or think they do, but I doubt that. No one escapes the havoc of adolescence unscathed.

Is loneliness an illness?

I think it’s a part of the human condition, a symptom of being alive. Look at them all on their cell phones, constantly having to be in touch with others who are supposedly leading more exciting lives than they are.

Loneliness may actually be a communicable disease. Many lonely people end up in the headlines, committing hideous acts of vengeance with their extremist views. For most it's the "quiet desperation" thing. A few end up in art school.

I’m all for art as the medicine for melancholy. Dance, music, painting, film, whatever. Even if it doesn’t become a profession, the act of making art improves the quality of your life.

I once knew a lawyer who told me that the only way he survived in his insensitive profession was by continuing with his piano playing.

Word!

You are, to paraphrase the film Raising Arizona, “especially hard on the little things” in the book. Are you not a pet person?

On the contrary, I love animals and need them urgently for a grounding in my life. In Home After Dark the animal killings – now done anonymously – hang in the background as a metaphor for the slaughter of innocence among my characters.

They’re a metaphor in the same way that – a decade after my story takes place, in the sixties – the Sharon Tate killings became a symbol for a whole generation whose break for freedom had gone off the rails.

They’re metaphorical in the same way that school shootings are a national nightmare for Americans today. Something is rotten at the core of our culture and it’s only getting worse. For us Americans, the fact that we have a prime example of toxic masculinity running amok in the Oval Office is absolutely the worst solution to the problem of violence in our midst.

Is there much of you in Russell?

Russell c’est moi! The place has changed. The face is not my face. The details are not the same, but Russell’s character – wary, removed, watching from the side-lines, a displaced person full of anxieties about his own identity and his masculinity – this is a portrait of the artist as a 13-year-old.

That said, Home After Dark is very clear on the cover that it’s a novel. Presumably it’s important that people don’t read you into the story too much.

No, no, they are welcome to read me in there as much as they want or are able to. To have any sense of verisimilitude I’ve found that a good novelist must put himself into his or her book, which, for the novelist, may include confronting the things that scare him the most. My 13-year-old Russell will do anything to fit in with his peers, even to the point of betrayal of another person.

For Russell, his collusion in a hideous fabrication results in a real tragedy for which expiation will be difficult to find. I never participated in a mishap of that magnitude, but I know that, when I was a teen, I betrayed and helped to exclude, some of the ones who longed to belong to my same clique.

It is that sort of thing – “What did I say? Did I hurt someone’s feelings?” – that still keeps me up at night, and rightly so.

The book’s visual style is wonderfully vivid; sketchy and yet precise. Do you look at other people’s work for inspiration?

When I was 21 and decided to be an artist, I had so many influences it would take a book to catalogue them and to explain why I chose them. Dürer for control of my pen, Rembrandt and Daumier for life in my line, Käthe Kollwitz for her huge compassionate gaze, George Grosz and Ronald Searle for their wicked satirical eyes …

I had a new artistic mentor every six months. At one point I was convinced I was the reincarnation of Egon Schiele (my hormones were still raging!) even though I continued studying the drawings of Rembrandt, knowing that he had arrived at a mature wisdom that Schiele never lived long enough to achieve.

These and many others were my artist kin. I recognised them by their line and the sense of life they brought to their drawings. I still keep a book of the drawings of Heinrich Kley near at hand to remind me, at a glance, that it’s possible to draw the human figure in any pose and from any angle, from memory.

It might interest you to know that I was never a comics aficionado. Films, especially the films coming over from Europe in the late 1960s, were the biggest influence in my understanding of visual storytelling, of things like pacing, rhythm, camera angles, mis en scène and so on. I was persuaded by Bergman, Polanski, Hitchcock and Antonioni that film is an art form to be studied seriously.

Home After Dark has already been compared to Lord of the Flies and Catcher in the Rye. How does that go down with you?

Ha! Thanks for the thrilling comparisons, but, unless I could extend the text and lend it something the words don’t, I would never desecrate such literary masterpieces! I still consider literature the greatest art form. Pictures – with their ability to get past all the guard towers and go straight to the heart – are fantastic, but dangerous, because they also can bypass intelligence, which is why they are such a great tool for propaganda.

Having said that, I have limited abilities with language and the visual is my best communication tool. That is the medium I must work in and, despite the time they take and all the pitfalls they offer, I love making graphic books.

I do have some as-yet undeveloped ideas for graphic novels. Each one of them has been tried and rejected for different reasons, but, instead of giving up on them, I’ve gone into my crouch, waiting for some light.

Home After Dark, by David Small is published by WW Norton, £19.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here