ALMOST the first thing you see when you enter Somerset House’s current Peanuts exhibition is Charles Schulz’s childhood baseball mitt. All scuffed leather, it sits in a glass box. A fetish item, a religious relic: you can take it either way.

The life and the art. When it comes to writers, artists, or musicans we so often want to know about the life more. Physical artefacts such as Schulz’s mitt bring us into the same material sphere as the artist. We are close – a sliver of glass away – to the glove that encased his hand. Which means we are one step removed from the man who created the most famous cartoon characters of the 20th century.

That closeness is part of the appeal of exhibitions like Good Grief Charlie Brown!, which is, it should be acknowledged, a considered and comprehensive take on the cartoonist and his creations

And yet the truth of it that everything about Schulz is in the work. His attitudes, his humanity, his craft and care. Do we need any more?

The Somerset House exhibition in London is a mixture of original comic strips, films, artefacts – like the baseball mitt and also Schulz’s ice skates – correspondence from the likes of Doctor Benjamin Spock, Timothy Leary and Ronald Reagan (all of them Peanuts fans), merchandising and published material (the true Proustian moment for me was not the Schulzian relics but the table full of old Coronet paperbacks; the books that were my own introduction to Peanuts).

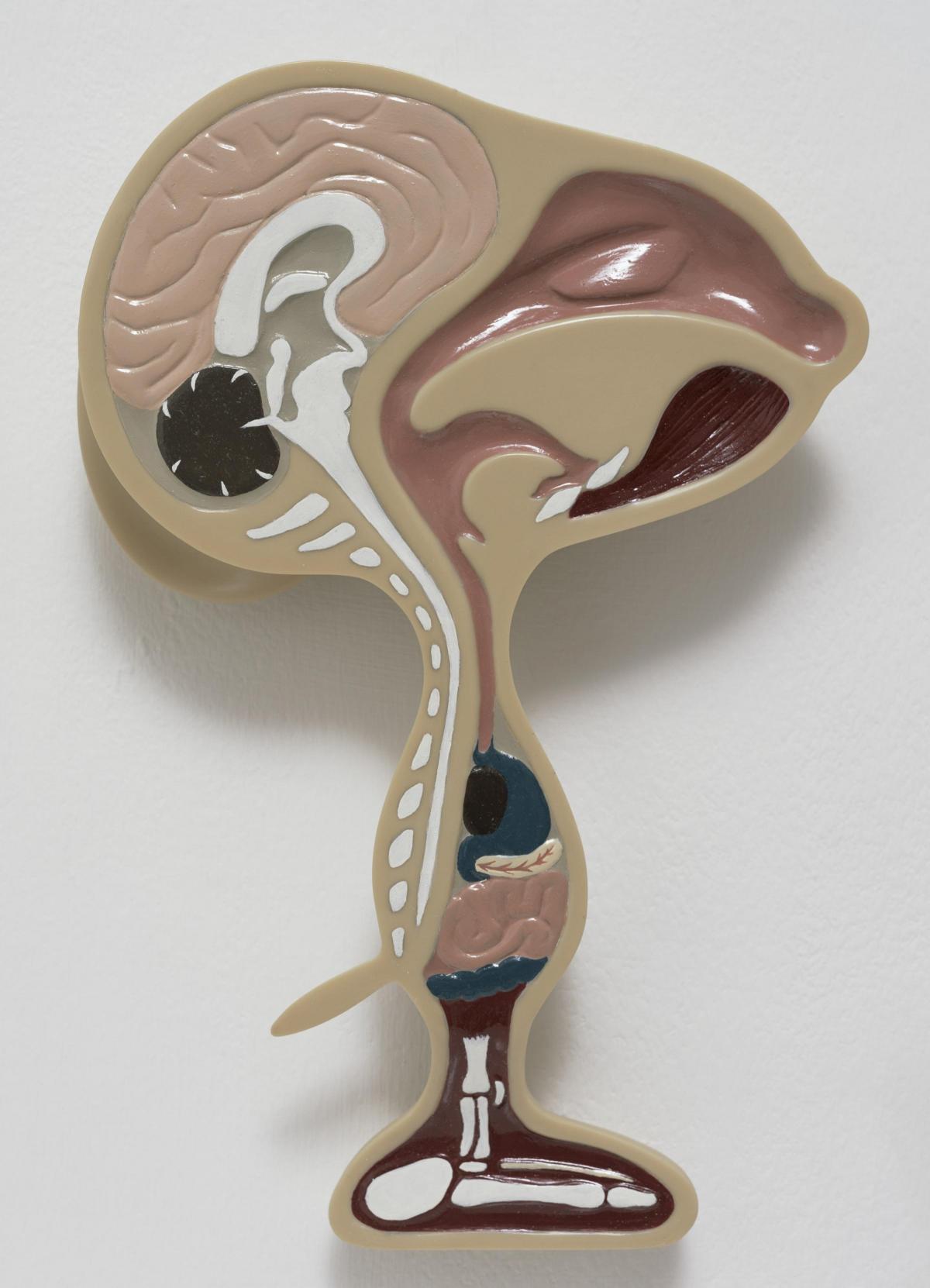

There are also artistic responses to the Schulz universe, which are, to be honest, of varying degrees of interest. That said, The Smiths fans in me loves Lauren LoPrete’s retrofitting of Morrissey’s lyrics to Schulz’s speech bubbles, and David Musgrave’s cross-section of Snoopy made me laugh.

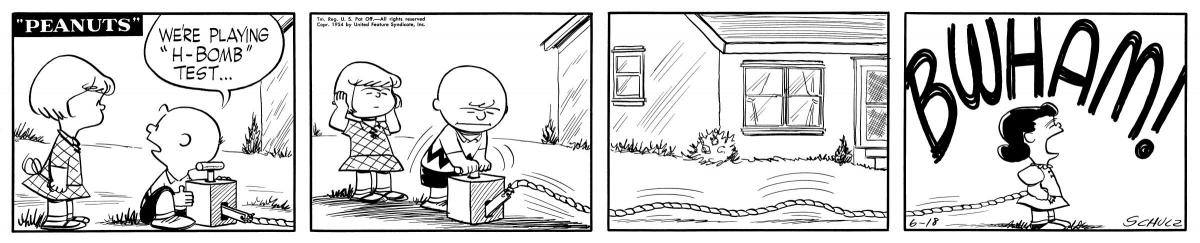

It’s a loving, informative, considered exhibition. But in the end, wandering around, I kept coming back again and again to the strips themselves and the way in which, with just a few lines and dots, Schulz created a world.

A world that also reflected our own. One of the key threads of the exhibition is its examination of how Schulz commented on American culture and society in the post-war years. Feminism, psychotherapy, the Vietnam war, race relations and the race to the moon all turned up in the strips.

And the strips filtered out into the world as well. In May 1969 Apollo 10 was launched to scout the landing site planned for the Apollo 11 moon landing attempt. The crew named the lunar module Snoopy and the command module was named Charlie Brown. (In return, Schulz created a storyline in which Snoopy visits the moon.)

And during the Vietnam war Snoopy turned up on the fuselage of American fighter planes and short-range missiles.

The characters had transcended their creator. All the more so as merchandising kicked in and Snoopy, in particular, was given the hard sell through the later years of the century.

That commodification had an impact on Schulz’s reputation. The warmth, humanity and existential yearning that can be found in the strips was increasingly smothered in memorabilia.

Indeed, right at the end of the exhibition there’s a reproduction of Art Spiegelman’s strip about Peanuts. In it the creator of Maus admits that for many years he had little time for Schulz and what he saw as the cosiness of Peanuts; the whole “happiness is a warm puppy” tweeness of the thing as he saw it.

And then he started looking at the strips again and realised that tweeness was not what Schulz was offering at all.

Away from all the stuff (and there was so much stuff) that surrounded it, Peanuts was full of empathy and craft and art. Peanuts is stoic philosophy in cartoon form.

As Schulz himself once wrote: “All the loves in the strip are unrequited; all the baseball games are lost; all the test scores are D-minuses; the Great Pumpkin never comes; and the football is always pulled away.”

The Somerset House exhibition is a lovely thing, but in the end everything you need to know is all in the strips themselves.

Good Grief Charlie Brown! Celebrating Snoopy and the Enduring Power of Peanuts continues at Somerset House until March 3, 2019. Visit somersethouse.org.uk for more details.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here