Think of a robot and the vast majority of us will probably conjure up the same vision – roughly humanoid, probably silver, flashing dead eyes and an “I-am-a-ro-bot” type of voice. Personal proclivities dictate whether yours is closer to the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz, a Terminator T800 or Star Wars' C3P0, but you get the general gist.

The word robot, coined from “Rossom's Universal Robots”, a 1920s Czech play by Karel Capek – the word robot meaning worker – might be new, but the medium it describes isn't. Curator Tacye Phillipson, Senior Curator of Modern Science at the National Museum of Scotland, the final stop on the UK tour of the Science Museum's blockbuster Robots exhibition, points out that we have been trying to create walking, talking human (and animal) replicas for well over 2,000 years. The cultures of the Ancient Egyptians and Greeks, of mediaeval Islam, all had their own jaw-dropping mechanical devices. This exhibition brings some of these historic automata together with robots of the future and provokes questions of exactly where on the spectrum of robot as human we feel comfortable.

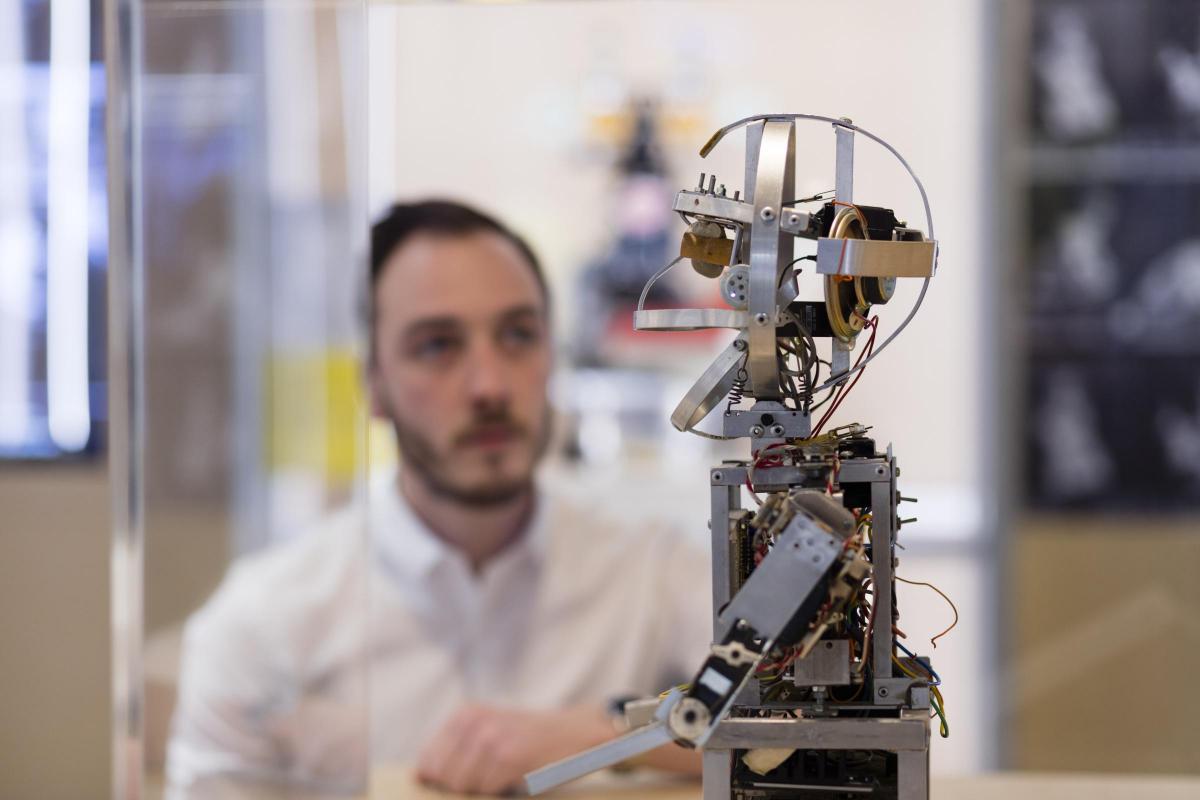

Make it past the somewhat creepy animatronic baby in the entrance – this is Phillipson's own 'robot too far' - and you will find a plethora of iconic mechanical people, including a replica of Maria from Fritz Lang's 1929 film, Metropolis, whose look inspired both reality and sci-fi. There is the flamboyant Cygan, a very 1950s Italian robot which, despite the decade of his construction, did not take mundane domestic tasks out of the hands of the housewife. There is Inkha, the sarcastic reception robot, which used to be stationed in the hallway of Kings College in London, now ready to interact with exhibition visitors. Her repertoire is limited, apparently, but she will probably give you short shrift.

There is also Robothespian – the first humanoid robot available to buy on the open market, provided you have a spare £50K. It can perform plays in 30 languages, tell jokes and sing songs, although for that money, you might note, you could probably go to the theatre every night of the week for the rest of your life.

And in amongst the 1960s tin robots from Japan and the futuristic robots of the Edinburgh Centre for Robotics (their top toy, NASAs Valkyrie robot, is not at the exhibition, but documented), there is the aforementioned T-800 robot endoskeleton from the Terminator films, for those who need reminding of the potential pitfalls of building artifically intelligent robots in our own image.

“I think when it comes down to it, we're either exploring the apocalypse or looking at an imagined utopia where we're all sitting down whilst robots wait on us hand and foot,” laughs Phillipson. The two are probably not mutually exclusive.

But it turns out it is very hard to recreate a working humanoid body in robot form, which may give some succour. The Valkyrie robot has a safety harness, Phillipson tells me, to stop it being damaged when it falls over. “I asked the researchers how often the safety harness comes into play,” she says. “They said “At least daily”. It's quite a young child that moves beyond falling over, which shows how hard it is to create something that can walk on two legs – or indeed how advanced the human brain is.”

A.I. Is certainly the 21st century game-changer in the world of automata, and there are some truly staggering innovations on display here, but perhaps some of the most fascinating material in the exhibition – if you are that way inclined, which I am - is the historic mechanical devices and clockwork forms, from the manikin that was built to demonstrate the articulation of the human body in the late 1590s to the 18th century drinking game automaton in the shape of a woman that, once wound up, twirls down the table holding a flagon of booze. Where she stops, nobody knows, but they will drink when the mechanism runs down. There are clocks and some wonderful orreries (mechanical models of the solar system), representative of those devices whose intricacy and magic delighted kings and emperors from ancient China to Istanbul.

In a way it doesn't, in fact, matter which era of automata we look at, whether futuristic or ancient – each can evoke a sense of awe – and chill - no matter that one works on an ingenious mechanical system of hidden wires, the other through an A.I. “brain”. When it comes down to it, modern day robotics researchers are, in a sense, still artificers trying to dazzle the king.

Robots, National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, 0300 123 6789 www.nms.ac.uk 18 Jan - 5 May, Daily 10am - 5pm, £10/£8/Under 16 and members free

Don't Miss

The 39th BP Portrait Award makes its annual trip to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery with its cargo of figurative experiments, some rather more successful than others. Known for its substantial prize money of £35,000, this year's winner, Miriam Escofet, was awarded top spot for her arresting portrait “An Angel at My Table”, a portrait of her elderly mother. Elsewhere the usual collection of children, lovers, strangers, friends, all depicted in a variety of styles, an insight into the world of portraiture today.

BP Portrait Award, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1 Queen Street, Edinburgh, 0131 624 6200, www.nationalgalleries.org Until 10 Mar, Daily 10am – 5pm

Critic's Choice

The Edinburgh School comprised a group of eminent and divergent Edinburgh College of Art students and teachers, loosely brought together under the figure of Sir William Gillies – Head of Drawing and Painting at ECA for fifteen years from 1946, then College Principal - whose ethos and aesthetic permeated the college in the mid twentieth century. Anne Redpath, Elizabeth Blackadder, John Houston, Robin Philipson, these - and many others - are the well known names that look out from yearbook and studio photos arranged in a display cabinet in the back room of the Scottish Gallery, which often gave the first exhibition to promising ECA graduates.

There is breadth in this exhibition, more than anything, the inked outlines of Gillies' watercolour landscape West Gruinard Bay stressing the importance of drawing underlining his practice, and by extension that of the Edinburgh School itself. Bright landscapes from John Houston stand out on the crowded walls, as do Adam Bruce Thomson's harbour scenes. There are tantalising snapshots of the artists in their studios, on holiday, larking about, which dot the exhibition and the accompanying print catalogue.

But it is in the small room of drawings that treasure lies, particularly the drawings of Wilhelmina Barnes-Graham – part of the so-called “Wider Circle”, and so-dubbed in her case for absconding to St. Ives – and Anne Redpath, each sketching out their evolving worlds, their unique and assured styles, whether found in a rural Fife farmhouse, a Cornish harbour or a marble quarry in Tuscany.

The Edinburgh School and Wider Circle, The Scottish Gallery, 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, 0131 558 1200, www.scottish-gallery.co.uk Until 26 Jan, Mon – Fri, 10am – 6pm, Sat, 10am – 4pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here