There Will Be No Miracles Here

by Casey Gerald

Tuskar Rock Press/Profile, £16.99

Review by Brian Morton

No one seems to go hunting for the Great American Autobiography, though it is memoir rather than fiction that is the key American literary mode, with dis-illusionment – so spelled and meant – as its defining subject. There probably should be no such subset as African-American autobiography, but on turning to Casey Gerald’s extraordinary book, one automatically thinks of such predecessors as Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison and, more recently, Black Panther writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose 2008 memoir A Beautiful Struggle reactivated the theme of father-son relationships in a striking new way.

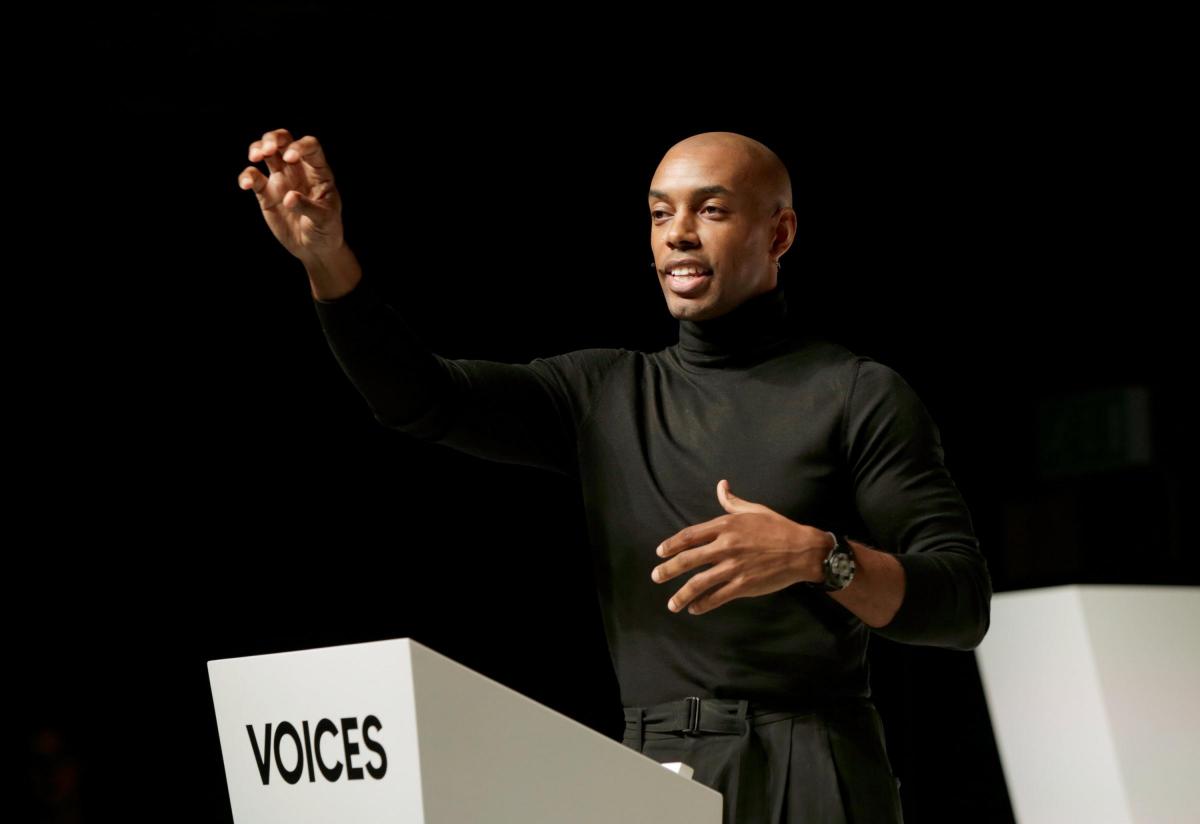

These are at the heart of Gerald’s book, too. In summary, his book seems like a standard trajectory – part mis. lit., part Horatio Alger - from a semi-orphaned childhood on the wrong (that is, black) side of Dallas, to an Ivy League education, Wall Street and a bite at the American Dream. Gerald’s father is a local football star who has lost his way to drink and drugs, but in whose sporting footsteps the young Casey steadily goes. For a moment, it looks as if sport is going to be his route up from the ground, in an ironic recasting of the infamous Ralph Ellison message in Invisible Man that suggests white society’s tactic with its young black men is to “keep this ****** boy running”. But we already know from the publicity material, and from frequent shows in the media that Casey Gerald took an MBA at Harvard Business School, made a speech there that went viral on the internet, and that he has become a TED celebrity and darling of the neoliberal centre.

So far, so (extra)ordinary; but There Will Be No Miracles Here is not a typical memoir. Its stream-of-consciousness approach reflects its composition by the “morning pages” method, three sheets of A4 every morning before coffee, without fail, until you have something like an MS to work with. Its themes, though, are profound rather than simply aspirational. Joan Didion is perhaps the American author who has most clearly and insistently set out the theme of dis-enchantment and dis-illusion, creating a “mixed” world in which magic and prosaic, tawdry reality always seem to bump up against one another (“the princess is caged in the consulate, the man with the candy will lead the children into the sea”), leaving her protagonists and herself becalmed on a plane of plain fact. Gerald, who is black and gay and was robbed of a “normal” childhood, takes this even further.

We first meet him, on the eve of the millennium, waiting in church for the Rapture. At 12:05 everyone goes home, if not content, then clearly neither disappointed nor unduly puzzled. Waiting for transcendence is steady work, until you learn that transcendence is perhaps an illusion that needs to be set aside. Gerald’s title comes from a sign allegedly set out by a French king who learned that subjects in a certain village were not doing their work but waiting to be the recipient of what seemed to be a local spate of miracles. “THERE WILL BE NO MIRACLES HERE BY ORDER OF THE KING” It should maybe have been written, instead of “Abandon hope . . .” above the entrance of every immigration hall in the US.

The young Casey takes his time to learn this thoroughly secular lesson, as he does to come to guilty terms with his own queerness, and ultimately with the discovery that in order to take possession of your life, you have to take possession of your death, too. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s second book Between The World And Me was inspired by the police shooting of a friend. America might allow African-Americans to live on equal terms, but not to die on equal terms. Gerald’s flirtation with suicide - which is the wrong word, since it suggests camp gesture rather than philosophical act – comes late in the book, but seems to hover across its entire length.

His account of growing up, reliant on grandparents and tough-tender sister, is genuinely moving. His largely absent father Roderick is a figure from sports page headlines and Hall of Fame reputation. His bipolar mother is also mostly AWOL, but unbelievably vivid when she comes back on the scene, even though we hear surprisingly little about her. Gerald’s deliberately mannered style very subtly skewers the half-truths and downright deceptions that surround the “typical” American success story. Some recent press headlines – for any of this young man’s pronouncements are now considered infinitely retweetable – had him saying that Donald Trump was the “worst” American president ever. What I read said that Trump was the “most American” president ever. The two things are not, of course, mutually exclusive.

There are things wrong with There Will Be No Miracles Here. Sometimes Gerald’s rhetoric has a self-fulfilling quality, as if the mere fact of his speaking should be sufficient. This is where a “morning pages” approach possibly falls down. If three A4s is your target, and you have eloquence to spare, you will not fail your quota. There are slips, which are as telling as they are seemingly trivial. Writing about a scholarship recruitment trip to Yale, Gerald describes a nightclub as being like the dungeon where Hannibal Lecter keeps Jodie Foster prisoner. Odd. Hannibal Lecter is the one who is kept in a dungeon, where Agent Clarice Starling, played by Jodie Foster, visits him. Buffalo Bill, the serial killer they are both notionally chasing, keeps a senator’s daughter in a dungeon, from which Clarice rescues her. Picky? Maybe, but Gerald has several lapses like this, stylistic flourishes that not only fail to come off but blunt the point he is trying to make. The nightclub in question is where he is sent with an “available” young woman, as an inducement to sign for the Yale team. The sexual politics are much more interesting than a throwaway line from a misremembered movie in which actor and character are blurred.

That is Gerald’s problem throughout the book. He is required by the dominant culture to act a part and read his lines. He even has the pressure of his father’s youthful celebrity feeding into that. And yet every instinct, social and sexual, plus God’s failure to deliver his apocalypse in the opening pages, points against such a passive surrender to the prevailing mythology. I thought several times while reading Gerald’s book about Calvin C. Hernton’s (that is Calvin Coolidge Hernton’s) Sex and Racism in America, an old book now and probably discredited several times over, not least for its failure to engage honestly with gay relationships and queer aesthetics. Gerald’s account is both a breakthrough and a disappointment. It is too long and calls out for more disciplined editing.

Everything ultimately has to fall short of being the Great American Whatever, otherwise the quest would end. Gerald’s has the promise to take autobiography on a step not just from James Baldwin, from whom he borrows a certain incantatory cadence, but also from Maya Angelou, and closer to both Harvard and the Civil War from Henry Adams and his The Education of . . . as well. That it falls short of its own promise is both disillusioning and a confirmation of its central message, which is that self-reliance and speed – the outflanking movements that gave the young Gerald his moment in the football spotlight – are the only way to avoid the crushing mass of American life. No miracles, just a lot of wind work and well rehearsed routines. Unfortunately, that’s how the book often comes across, windy, self-regardant and pat. But there is something grand and deeply moving there as well, struggling to get out but also struggling to get back home.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here