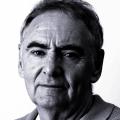

STEVE Carson, the new boss of all things BBC Scotland – including the new digital channel – rewinds on a story from his primary school days which I realise to be a neat metaphor for the task ahead.

“I have flashbacks in my mind of school in 1970s Belfast performing Scottish country dancing, up there on a tiny stage,” he says, grinning. “Part of me was trying to get my steps right – while another part of my brain was trying desperately to stop me falling off the edge.”

Today, Carson has to remain in tune with the Scots audience, replicate the traditional moves we’ve enjoyed over the years. Yet he has to create new dances, while avoiding going over the edge and smacking his face on the cold linoleum of public opprobrium.

But besides the country dancing trauma, what else suggests he can survive in the fraught, fickle world of television content?

Carson was born in Belfast in 1968, a year before British troops were moved in which confirms he grew up alongside, and having to negotiate, conflict. Carson’s father, Tom, was a journalist with the Belfast Telegraph and he and his mother were members of the Alliance party so pragmatism and resolution were home-schooled from an early age. “My father would have been a big influence on me and he shaped me in so many ways,” he says.

Yet, his mother didn’t have the same opportunity. A week before his fifth birthday his mother, Patricia, was taken by cancer, aged 49.

That certainly forms character, Steve? “It does,” he says, in soft voice. “I’ve gone through phases with this. When you’re a child you get on with it, I suppose. But when I had my own children [he has three sons] it made me really feel the loss. And as I’ve gotten older I can now see my mother’s loss. She didn’t get the chance to see her family [he has two older sisters] grow up.”

His words darken: “When I reached my 49th birthday it was far more emotional for me than my 50th.”

Tom Carson coped. “He had to. In the 1960s everything had seemed possible for him. But the Troubles were the collapse of all his hopes – and then his wife dies. Anyone left with a young family in a city that’s burning down around him has it tough.”

Perhaps the schoolboy Steve Carson would have become fixated with television regardless. But it’s not hard to see why living in the most dangerous city in Europe could have accentuated the escape into the box in the corner. “I grew up a TV addict,” he says with a wry smile. “When my dad got home I’d be in front of the telly, pretending to do my homework. As a young boy I can remember walking past the BBC building in Belfast and being so intimidated by it. I had no idea how to be part of this world.”

READ MORE: BBC Question Time slammed over 'misrepresentation of Motherwell and Wishaw'

Television wasn’t his only obsession. Carson, at 16, looked like an extra from Quadrophenia, a parka-covered Mod with a huge pile of soul records whose mind raced to a Green Onions beat. (Which also hinted at young man prepared to look back for influence, and looking to belong?)

Aged 18 however, the parka and Belfast was abandoned for university life in England, studying politics and history. “We were a generation reared for export,” he admits, of the impact of the Troubles. “I was aware every normal functioning society needs young people to be actively involved but my lot just buggered off.”

Carson offers a partially apologetic smile. “It was also about yearning for new horizons. I was leaving a city centre that was closed after six o’clock.”

Did he go to university with a view to making a career at the BBC? He says not. “I knew that people who landed jobs at the BBC went to Oxbridge, and had parents in the House of Lords.”

Carson maintains he had a fall-back position of becoming a history teacher. Yet, what he did next contradicts that. “In my final year, I was working for the student newspaper and I got the chance to do work experience with BBC North. Thankfully, I had the presence of mind to know the most important person was the production manager, so I wrote down his name and later that summer while working in a bar I went to a phone box and rang John Stafford to see if there was any work at the BBC. He said ‘Funny, enough. There’s a runner’s job.’”

Ah, so you did see the dream could become a reality, Steve. “It was right time, right place,” he maintains.

Perhaps. But in landing a youth programmes job bossed by Janet Street Porter, Carson would make coffee and come up with programme ideas. “She was a force of nature,” he recalls of JSP. “And I loved the open culture.” The boss was also rather eccentric. On one occasion, after one of his early items had aired, she ripped into Carson for wearing a green shirt. “She said it wasn’t what young people wore.” Who knew?

READ MORE: Stephen Jardine to host Scotland's Debate Night on BBC Scotland

Did the then 23-year-old, with obvious good looks and easy manner, reckon he could make it as a presenter? “I figured I was OK but I was never going to make a living at it,” he says. “I wasn’t Johnny Vaughan.”

His talents lay elsewhere. Producing. Directing. Carson went through a ten-year period, working his way up the ladder, through programmes such as Panorama. Yet, when he finally landed a full-time contract he walked away to go freelance, and set up his own production company. Now, this suggests a little craziness, or that his cojones had been welded at Harland and Wolff?

“It sounds cheesy,” he says, “but I was moving to Ireland to be with someone I loved and we were having a child.”

In 1995 Carson met Dublin-born journalist Miriam O’Callaghan while working on a film about the Famine. Together they set up Mint Productions in Dublin, with an office in Belfast. “It felt the natural thing to do,” he says.

Success reveals it was also the right thing to do. The couple’s sideboard was soon top- heavy with awards for their critically-acclaimed documentaries. Carson’s talent was then recognised by RTE, which made him director of programmes. More success followed and in 2013, he rejoined the BBC, going on to become Northern Ireland’s head of content production.

It was clear Carson ticked all of BBC Scotland’s boxes for the new role. But it’s when he talks more of family and history you understand why he could well make a success of the job in Scotland; there’s an implicit need to understand people and culture.

Ten years ago, Carson delved back into his mother’s past and discovered that in 1920s Ireland her parents were of a mixed marriage. “My grandfather was an ex-junior UVF member who married a Catholic from the Springfield Road,” he says, “and there’s an IRA connection in the family as well who was sentenced to death in the Crumlin Road jail. Perhaps that’s why I’m so fascinated with social history. Lives are always so much more complicated when you look in and pick away layers.”

He wants to pick away at Scotland’s layers. Last summer he jumped on his bike and cycled around the country for fun and “soakage of culture.” Carson wants to soak up even more. “It makes it easier knowing Scotland and Northern Ireland have so much in common, such as a really dark humour.”

Carson hopes to reflect the diversity, the confusion of Scotland today. And the sense of fun. Will he make a success of it? Well, anyone prepared to race a tiny two-wheeled Italian death trap around the wet streets of troubled Belfast should be able to negotiate Scotland’s television landscape.

“Perhaps,” he says, laughing. “I don’t know if I’m brave – or I just have no self-awareness.”

BBC Scotland’s digital channel starts on February 24.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here