WHAT HELL IS NOT

Alessandro D'Avenia

Oneworld, £14.99

Translated by Jeremy Parzen

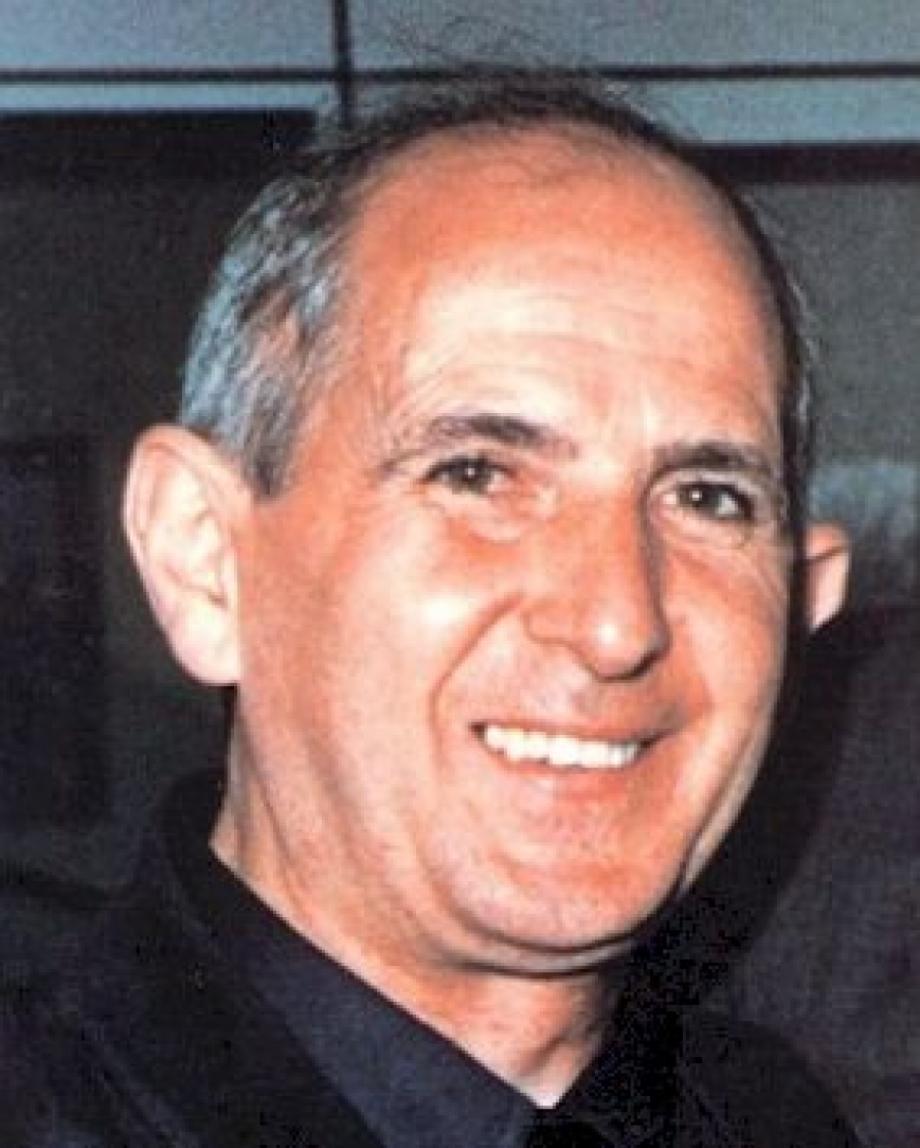

TO the Mafia in Palermo, in southern Italy, Padre Pino Puglisi was a troublesome priest, an outspoken opponent of its malignant ways. To the people of Brancaccio, a tough, run-down local neighbourhood, controlled by the Mafia, he was something of a hero, always speaking up for them, working for them, seeking to do something positive for the children.

One day in September 1993 - his 56th birthday - Padre Pino was gunned down by the Mafia. He died in hospital. "This is a Mafia crime," an investigating magistrate was subsequently quoted as saying in the New York Times. "Cosa Nostra could not stand that priest's teaching the kids in the neighborhood about an anti-Mafia culture."

The fate of this brave man, who was beatified by the Vatican in 2013, has long troubled, and fascinated, Italy: a book was written about him, and a film made. Now Alessandro D'Avenia, a successful novelist (and teacher at a high school in Milan) has taken the facts of Don Pino's life and death as the basis for his third novel. It is no surprise to learn that it has sold in excess of 350,000 copies in Italy to date.

The book, set in 1993, is largely narrated by Federico, a sensitive, bookish, 17-year-old boy from a privileged local family, the sort of family to whom Brancaccio might well be on the dark side of the Moon. Federico, whose literary hero is Petrarch, is in love with words, and their power. "I believe that someday I will be a poet," he observes. "I might already be a poet but a poet who leans towards baroque exaggeration."

Federico is bound for Oxford to study English, but his plans are derailed thanks to a chance encounter with Don Pino. At length, having fallen under the kindly priest's spell, he abandons his plans in favour of working with the older man as he tries to improve life for the children of Brancaccio.

The chapters set in this industrial neighbourhood have a power of their own. D'Avenia convincingly conveys the extent of the deprivation and of the reach of Mafia's influence and control. The ragged children have nothing to do all day long; many of them do not go to school. Lost, undernourished, ignored, they roam the streets. Cats, dogs and lizards are, now and then, tortured, just for fun. Don Pino, himself a Brancaccio man, knows what it is like to have been such a child. Now, he counsels love, and preaches infinite patience.

Federico has been assaulted by one boy, but Don Pino counsels the teenager to love, not hate, him: "Loving children like him is the only thing that can change Brancaccio,” he says. “Judging him is too easy."

Later, in a passage that gives rise to the book's title, he advises Federico: "If you are born in hell, you need to see at least a fragment of what hell is not to understand that something else exists." The children themselves, it turns out, are proof of this: they have overcome their natural suspicion and have fallen in with this older man who wants only to encourage the seedling of goodness that grows inside them.

Don Pino wants to open a pre-school and a middle school for the children, a social and health services office, and "a little bit of green where the kids can play and run around," but for the last three years he has been thwarted at every turn by bureaucrats and by the local police. Characteristically, he persists, but his ceaseless efforts, and his occasional anti-Mafia pronouncements, unsettle and infuriate local Mafia figures, such as the ones referred to here as Mother Nature, and The Hunter. Eventually, they decide that enough is enough.

D'Avenia has a lyrical touch amidst the violence and the squalor. Local girls wear "bathing suits stuck to their smooth skin, taut as the drums of an imminent war". Oversized trees "explode from sidewalks". There are allusions to Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, the Palermo judges and prosecuting magistrates, both of whom were slaughtered by the Mafia.

You know what is going to happen to Don Pino on September 15, 1993, but so vividly has he been drawn here that you wish he could somehow avoid his fate. Still, you are left to remember, with sadness, the redemptive power of all that he preached.

"Don Pino is a don without power, a don without strength," Federico observes, early on. "His strength is unarmed. It's not greater than violence because violence transforms the flesh. But it goes [italics] beyond [italics] because his strength transforms the heart."

In real life, at least, several Mafiosi were jailed for life for the killing of Puglisi.

Russell Leadbetter

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here