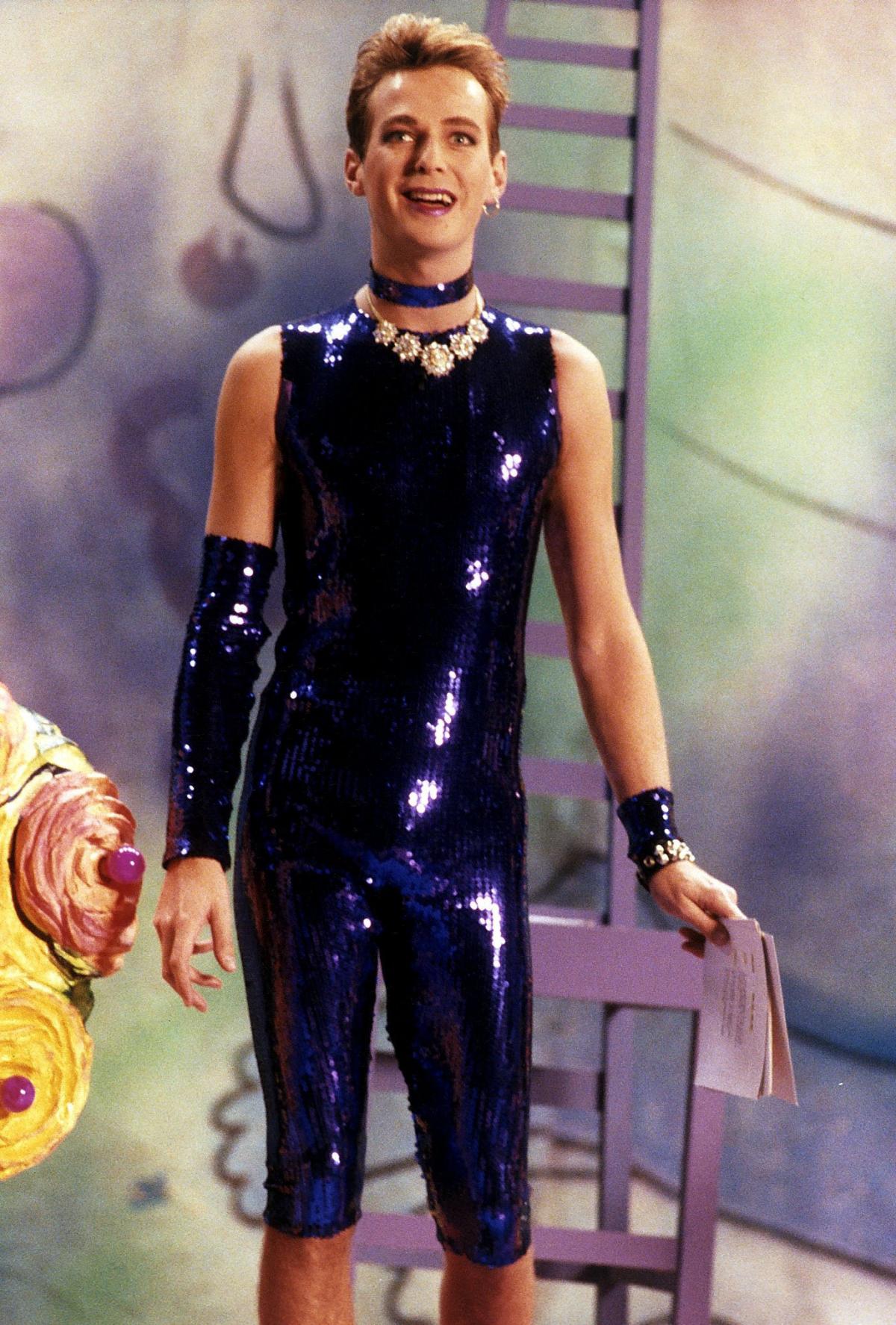

If you’ve followed Julian Clary’s stand-up career over the last decade or so – or just seen the tour titles listed somewhere – you’ll have detected a theme. The shows have included, in no particular order, The Joy Of Mincing, Natural Born Mincer, The Mincing Machine and Lord Of The Mince. Here, then, is a definition of mincing from the man himself, delivered after a short pause for thought and reflection.

“I think it’s a sort of relentless statement of joy in your own sexuality, or in your own eccentricities,” he says. “Things that might be considered a disadvantage are turned to assets, really. So it’s kind of a declaration of self in the face of possible objections.”

I tell him that brings to mind Quentin Crisp, whose entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography lists his significant achievements as writing and acting but who is more usually celebrated as a trailblazing and flamboyant gay man who flouted convention when it was dangerous to do so.

“Yes, I think he said that life was a dash from cradle to grave under heavy fire, or something like that,” says Clary. “I’m aware it’s an old-fashioned word but there’s someone who lives around here who minces past my house every day and I think ‘Well, how marvellous. He’s just sort of mincing around declaring himself whether he’s conscious of it or not. He doesn’t care’.”

Crisp, of course, was an influence on Clary. How could he not be?

“The Naked Civil Servant was on television when I was at an impressionable age [Crisp’s 1968 autobiography was adapted for TV in 1975]. He was a complicated man, I think, Quentin Crisp. I liked that bravery and fierceness that he had … I often think that life was quite tough in the 1980s when I was starting out on the cabaret circuit, but it was nothing compared to what he went through. It [homosexuality] wasn’t even legal in his day.”

Clary even met Crisp once, taking advantage of the older man’s habit, while living in New York in the 1980s, of hooking up with anyone prepared to buy him a meal. Dinner with Crisp was once said to be the best show in the city.

“I went on the Staten Island ferry with him,” Clary recalls. “He was amazing, but he did sort of talk in anecdotes, so you got the impression that whatever question you asked him you were going to get the same anecdote anyway. But he was one of those people where you never knew what he was really like because everything seemed to be performance.”

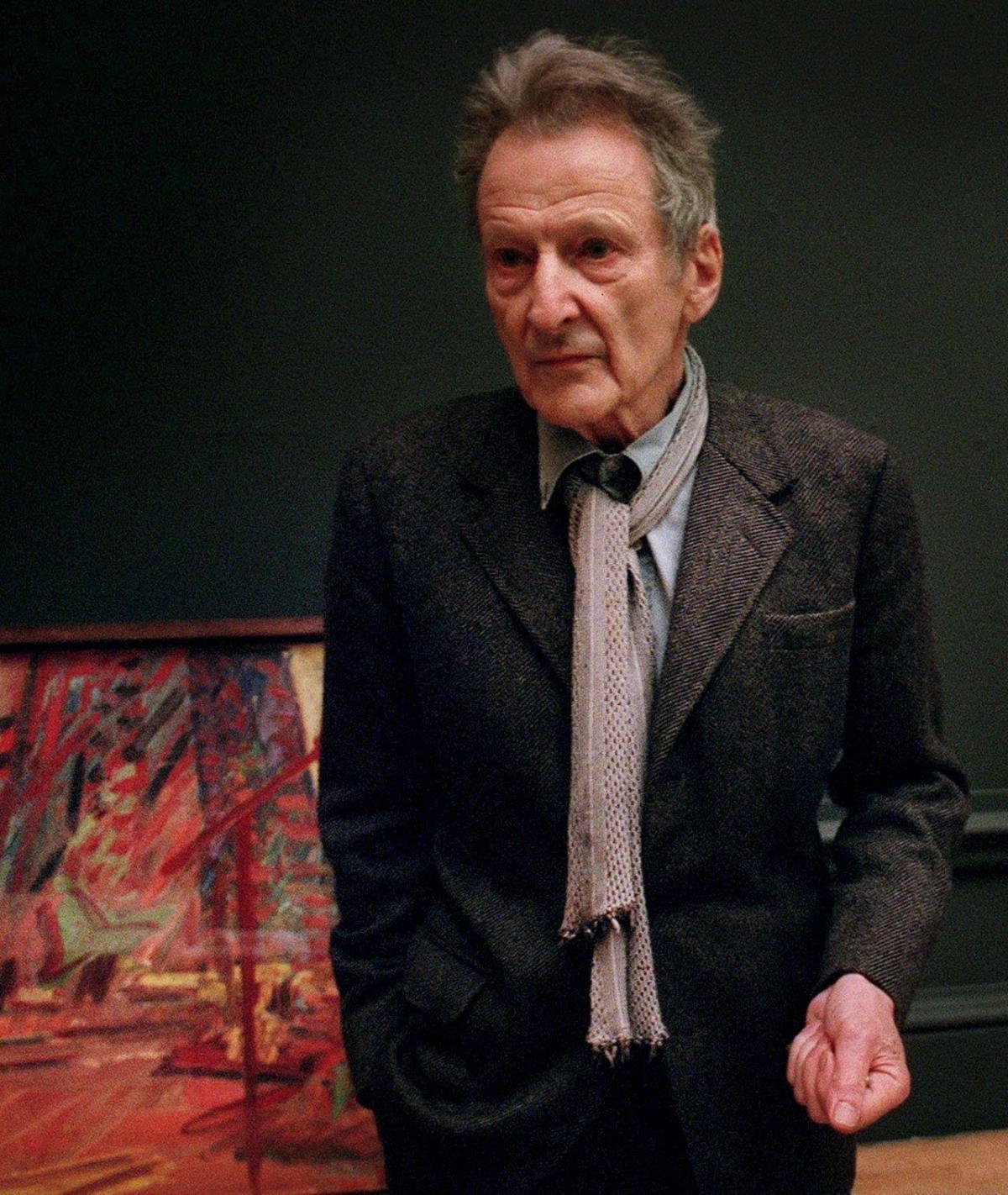

Another icon in the LGBT pantheon whose life and art revolved around performance was Leigh Bowery, the Australian-born scenester, club promoter and designer who became one of Lucien Freud’s greatest muses and who died of an AIDs-related illness in 1994. Although Clary’s current beat is on middle-brow platforms like BBC Radio Four, where he’s a regular on panel show Just A Minute, or on programmes such as Strictly Come Dancing and Celebrity Big Brother, the 1980s found him frequenting the same cutting edge London clubs as Bowery and his great friends Boy George and Michael Clark, the Aberdeen-born dancer and choreographer.

“I did meet him a few times,” Clary recalls. “I was going around to the same clubs where I would see Leigh and all that set of people and they were sort of living art. But I found it all a bit self-conscious at the time. It was all a bit ‘Look at me!’.”

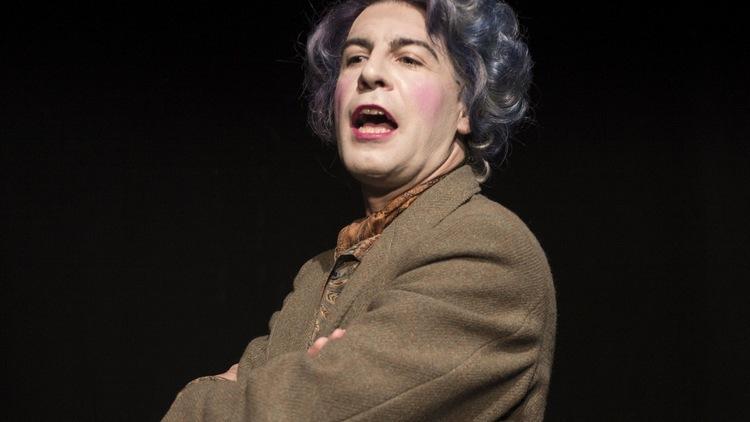

A musical based on Bowery’s life and named for the underground club he founded – Taboo – opened in London in 2002 with Boy George playing Bowery. Clary took over the role in late 2002 and also starred in the 2004 touring production. Sadly, it didn’t feature one stunt the real Leigh Bowery pulled, and which Clary had the fortune to witness.

“I saw him do a performance once where he swung on a sort of trapeze over the audience,” says Clary. So far so good. “But before he’d gone on stage he’d filled his rectum with water using some sort of enema contraption and then he just sprayed this all over the horrified punters.”

I could listen to these sorts of stories all day but I’m aware we’re straying slightly from the topics at hand, namely Clary’s upcoming Scottish shows – stops number eight and 20 on his 51-date Born To Mince tour – and the latest in his ongoing series of children’s book centred around a family of hyenas living in Teddington, the affluent London suburb the teenage Clary once called home.

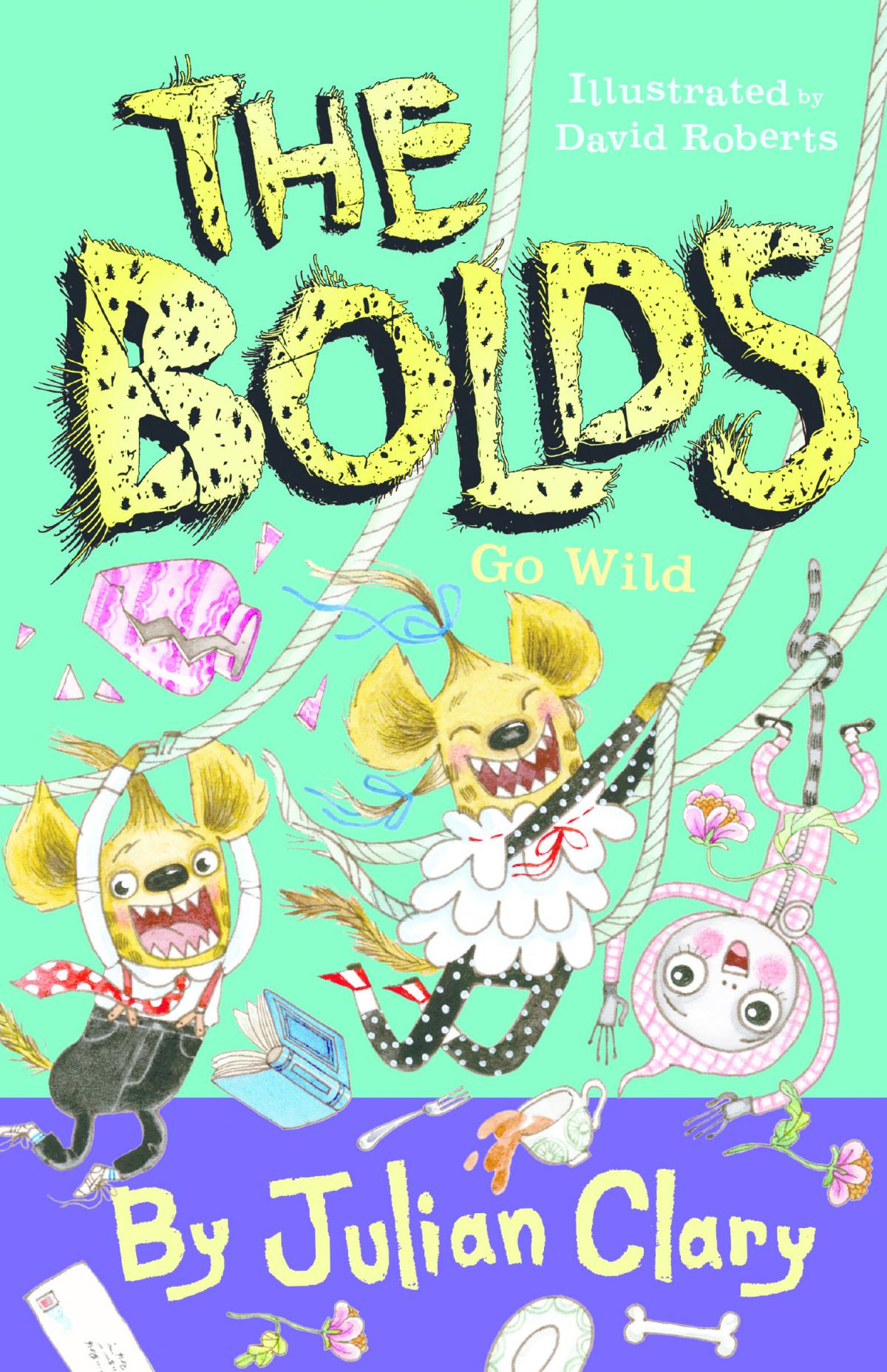

The family are called the Bolds and their last outing, The Bolds’ Great Adventure, was chosen as one of the 2018 World Book Day titles. The Bolds Go Wild, the sixth title in the series, is published next week, once again illustrated by the in-demand David Roberts (you’ll know the name if you have kids or grandchildren under the age of 12). The success of the series has introduced Clary to a new audience and taken him onto the book festival circuit. Is it a tough crowd?

“No, they’re lovely,” he laughs. “They don’t know who I am, and nor do they care, it’s just about telling them the story. It particularly seems to be the seven to 10 age group for The Bolds and it’s a very accepting age. They accept the unlikeliness of the story and they go along with it. I ask them if they’ve got any ideas when I’m doing the signing afterwards and they have such a strong imagination at that age. There’s no cynicism. So I really like it. I like talking to them.”

Born To Mince, meanwhile, picks up where Clary’s last show, The Joy Of Mincing, left off. Which is to say it’s more of the same but with different bits, and broadside after broadside of the filthy double entendres he knows his audiences love.

“My shows aren’t particularly about anything,” he admits, “but I’ll be talking about what’s going on in my life, singing a few songs and then I’ve got a whole section about heterosexual aversion therapy where I’ll be experimenting on members of the public – in the interest of light entertainment.”

And what has been going on in his life? “I’ve bumped into a few old flames, so they’ve given me some material. I suppose as I’m getting older as well I’m kind of interested in health matters and improving my life, which I’ll be sharing with people. Not in a serious way, you understand.”

In fact Clary is about to turn 60. The big day, for the record, is May 25 (he’ll be in Bury St Edmunds). It’s the same age Quentin Crisp was when he published The Naked Civil Servant, though Clary doesn’t need to know that fact to realise it’s a time to take stock and to reflect. He seems to have been doing both recently, telling one tabloid that he plans to retire when the numbers roll over.

“Well it’s rather appealing sometimes,” he answers when I ask if it’s true. “But then someone said to me yesterday ‘What will you do if you retire? Just stare out the window all day?’. I don’t think I’ll ever retire but I think I might not ever tour again. But I’m loath to say this is the last tour because I don’t know how I’m going to feel in five years’ time. I might think it’s delightful to go on the road again, so I rather lamely say it might be the last tour because I can’t predict the future. But I quite like being at home and writing and doing a bit of acting. There are other ways of expressing yourself.”

One way might be to pen a second volume of autobiography and he’s currently in discussion with publishers about doing so. A first volume, A Young Man’s Passage, was published in 2005 but only covered Clary’s early life and his years on the club circuit as a confrontational stand-up performing first as the Joan Collins Fan Club and then under his own name. It ran up to the infamous “Norman Lamont” incident – a risqué comment about the then-Chancellor made by Clary on TV during the 1993 British Comedy Awards – but its most heart-breaking chapter involved the death of Clary’s boyfriend from an AIDs-related illness.

Clary’s life since the mid-1990s hasn’t exactly been plain sailing but as he has glided into stardom and middle age nothing has occurred which can rank alongside the homophobic bullying, illness and bereavement which featured in A Young Man’s Passage. If the first volume dealt with difficult subjects which may still have felt raw at the time of writing, would a second volume be easier? All he’ll say is this: “Everything that’s happened in life is kind of locked in your brain and it’s quite interesting to look back and see it in a different way.”

If Clary is going to open up and reflect he’s clearly going to do it on paper rather than in an interview or on a stage. His stand-up show, after all, is about giving audiences a good time with a familiar face. “A lot of what I do is escapism,” he says at one point. “I know that when times are a bit grim I tend to have a better time on tour. I’m not going to be talking about Brexit on stage, it’s just going to be general filth and I think people can forget everything else. People are just doing the best they can, aren’t they, in places like Horsham or – where else am I going? – the Isle of Wight. People are just getting by”.

At the same time, however, he can’t escape Norman Lamont and nor should he. Clary, in his pomp in the late 1980s and early 1990s, was an unapologetic and confrontational stand-up during a dark time for the UK’s LGBT+ community and if he’s now viewed as a sort of elder statesman it’s only fitting. But is there still a need for confrontational stand-up where sex and sexual identity are concerned, or it a case of job done as far as he’s concerned?

“It is to an extent, so there’s a different kind of feel to things from when I started and when I enjoyed all the outrage. However there are things like gay conversion therapy, which does go on still much to everyone’s amazement. I think that is a rich area to be satirised and that’s sort of what I’m doing in this tour.”

So there is still a political element to his stage show, just as there are new battles to be fought even as the old ones – acceptance of gay people, for example, or the legalising of same-sex marriages – have been won and consigned to history.

“I think things are always going on to the next stage and people are always scared of things they don’t understand,” he says. “That’s really what was going on with homophobia some decades ago. It was really ignorance and part of what I was doing was demystifying it and now people need to get their minds round the idea of trans folk and also the whole gender fluidity thing. That’s very interesting. I’ve just read Diary Of A Drag Queen by Crystal Rasmussen. It’s about being exactly who you want to be and not being defined by one gender or another. I can’t argue with that, really.”

As he talks a thought occurs to me. What would the angry, fired-up, PVC catsuit-wearing 30-year-old Julian Clary make of his soon-to-be 60-year-old future self?

“I think he’d be fine with me,” he replies. “I’m calmer and happier and less needy than I used to be. I think that just happens as you get older.”

He’d be surprised that Clary is hitched, though. The comedian married long-term partner Ian Mackley in a low-key private ceremony in 2016.

“Well yes, that was never really thought off as a possibility when I was 30. So no, he’d think ‘Well fancy!’. And he’d probably think I’m quite conventional now in many ways.”

Maybe, though he’d take pleasure in the tweet Clary sent celebrating those un-anticipated nuptials: “On Saturday he slipped his finger into my ring,” he wrote. Some things never change.

Julian Clary: Born To Mince is at the King’s Theatre, Glasgow on March 23 and the Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh on April 10

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here