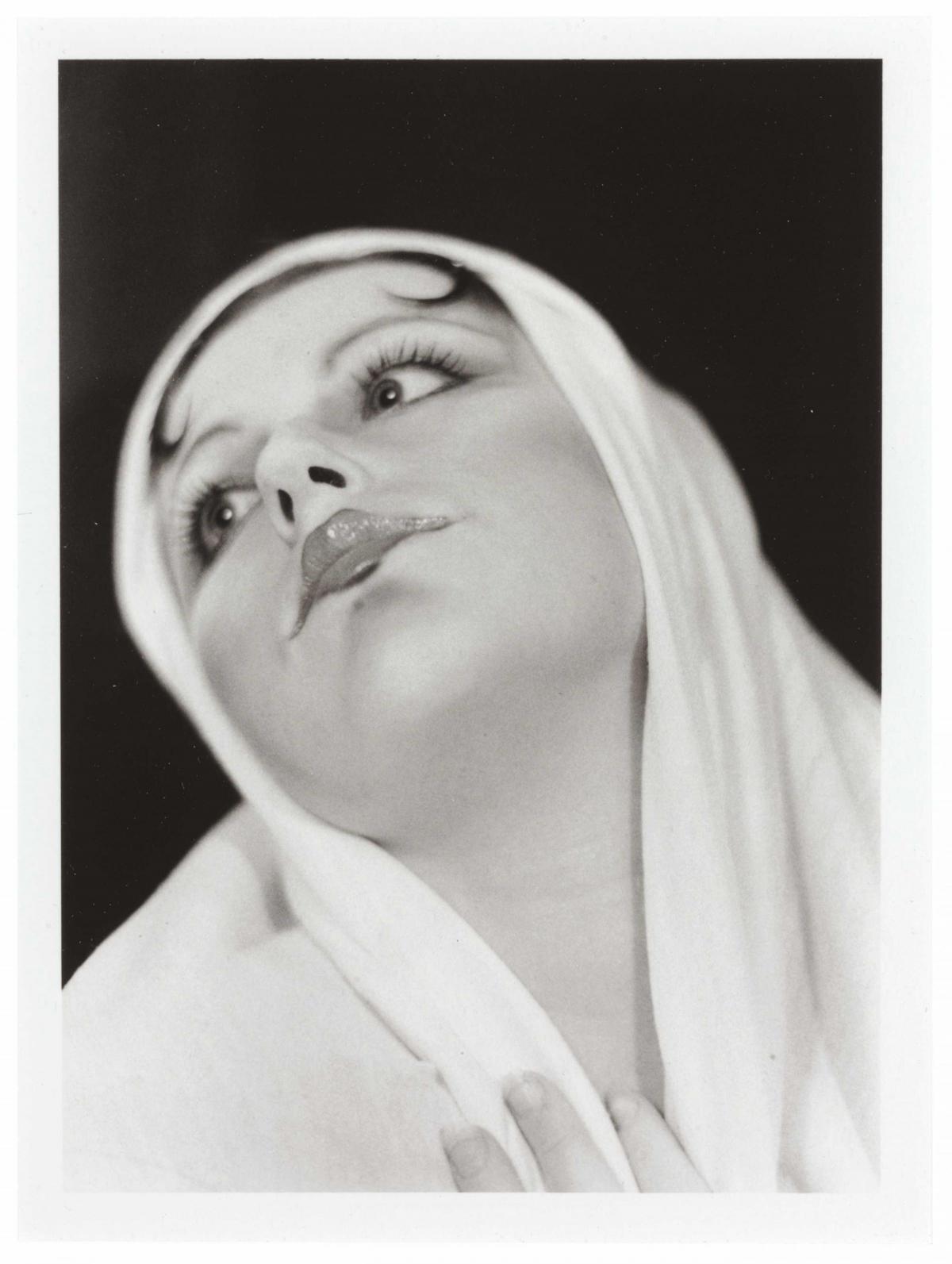

Outside in the hall, the tick tock of the old clock sounds through the high walled, cloistered space. A church of old, still a meeting place, although one of artistic minds, now, this exhibition of self-portraiture shows four artists, delicately linked. Captivating, thought-provoking, this exhibition is rooted, we are told, in a comment made by photographer Cindy Sherman, represented here by “Untitled (Madonna)” (1997), in which the artist appears, close-up, as a veiled matinee idol, head thrust back, lips distorted by lipstick lines that tweak them into exaggerated forms. “I feel I'm anonymous in my work,” said Sherman. “When I look at the pictures, I never see myself; they aren't self-portraits. Sometimes I disappear.” It is, here, a question of self-portraiture, of what is and isn't a portrait of the artist or the human, and of existence and representation, theirs and yours.

The exhibition opens with the ephemeral work of Francesca Woodman, who died aged just 23 in 1981. You can see the ghost of early 20th century surrealist photography in the work, but there is also the close examination of the self and the body in relation to the space it is in, a precision in the set-up, a blurring of boundaries made technically by long exposure photography that implants the figures within the space.

In Woodman's art, the walls around where she places herself or her female models are decaying, crumbling. Her physical presence is enmeshed with this, although there is nothing solid in it. In one of her series of works from Rhode Island (1976), two of which are shown here, the body which is only partly seen is echoed in a part imprint on the floor, a ghost, rather as if the body, there, sees the soul displaced, the jaunty Mary Jane shoes seeming to delight in the dichotomy. Elsewhere, a figure, joyful, emerges from split wooden doors, there and not there, cut off yet existing.

In “Untitled, Boulder, Colorado” (1978), we seen a room with a door, a chair, and then finally, only if we stay and really look, an arm reaching in from the side. The presence is dual - her bodies, herself or others, are both part of the fabric, but distinct.

Zanele Muholi, who is based in Johannesburg, created her most recent body of images, “Hail the Dark Lionness” after leaving her home in Cape Town some ten years ago, after it was ransacked and all the material charting her visual activism - asserting the rights of women, of LGBTQIA people, to existence - stolen. The works she has produced in these last years are stark, immediate, focusing the gaze on herself as subject – or object – of the image. This year she has been chosen to represent South Africa at the Venice Biennale.

The arresting images shown here, all works from the past three years, are “self-portraits” of the artist, seen through and with and beyond the materials that she uses, piled up and on and around her. In "MaID III, Philadelphia", ominously, she has coiled rope and clamp clips wrapped around her head, more rope around her neck. In “Basizeni I, Amsterdam” (2016) she is weighted in sunglasses. In “Thulile II”, Umlazi, she is strongly present, behind a wire fence, a bucket on her head, plants. There is always the direct stare that challenges the viewer, the existence that will assert itself despite all the elements, the good and the bad, that mount up – whether the artist's own or that of the world surrounding her. The artist gives us something to look at, wilfully, to subvert the centuries of “the black body that is ever scrutinised,”, but at the same time, we have to be looked at ourselves, to suffer the ghost of the scrutiny to which Muholi so starkly and devastatingly alludes.

Finally, Oana Stanciu's left-field takes on presence, her hair plaited like horns in “Buffalo” (2016), her eyes averted, suspended on a plank between chairs that sags beneath her weight. Then again, upside down, the image upended, on a stool, planted firmly on the ceiling, her inverted head viewing us right ways up – a jolt. Elsewhere she is a one-legged form facing the wall, or a truncated torso in an oversized cardigan, feet sticking out the bottom. There's more than a hint of Woodman in this, but there is also a very distinctive tendency to the outlandish, softly spoken - a gentle challenge to expectations.

Sometimes I disappear, Ingleby Gallery, 33 Barony Street, Edinburgh, 0131 556 4441, www.inglebygallerycom, Until 13 Apr, Wed – Sat, 11am – 5pm or by appointment

Critic's Choice

This fascinating exhibition from photographer Roger Palmer is inspired by Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who, in the early 18th century, was put off his ship in what appears to have been a misjudged battle of wills with his Captain, and lived alone on a Pacific island for four years, apparently inspiring Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe. Palmer's exploration of Selkirk and Crusoe combines fact and fiction, blurring boundaries in a juxtaposition of landscapes from Lower Largo (Selkirk's birthplace) to Isla Robinson Crusoe (then, Mas a Terra, where Selkirk was marooned), four miles off the Chilean coast.

Coinciding with the 300th anniversary of the publication of Robinson Crusoe, the exhibition includes a series of large-scale wall drawings which Palmer is making on the Kirkcaldy Gallery walls, alongside photographs taken on Isla Robinson Crusoe – now very much inhabited. Palmer, too, draws much from JM Coetzee's retelling of the Crusoe story, “Foe”, which deals with the issues of race which Defoe's original so starkly presents. Palmer's initial inspiration came from an old German children's edition of Robinson Crusoe with illustrations by Willy Planck, which Palmer found in a bookshop in South Africa.

Palmer's own photos explore the coastal regions he locates in Fife and Chile, his emphasis on the mid-line horizon, on looking out to sea. There are no people in the photographs, although there is evidence of life. He links maps and illustrations, the notions of the blurring of the real and fictional. On which point, Palmer points out, there is an island 90 miles west of Isla Robinson Crusoe, out in the vast Pacific. It is called Isla Alejandro Selkirk.

Roger Palmer - Refugio: after Selkirk, after Crusoe, Kirkcaldy Galleries, War Memorial Gardens, Kirkcaldy, www.onfife.com/venues/kirkcaldy-galleries 01592 583206 Until 23 Jun, Open daily - opening hours vary, see website

Don't Miss

The unmissable Natural Selection continues its tour, this time to Arbroath, courtesy of Hospitalfield. Natural Selection is a story of birds and their eggs, of evolution and necessity, and of the obsessive collectors who stop at nothing to illegally take those eggs out of the birds nests. It is also a cross-species story of father and son, of knowledge passed down in the bird world as in our own, and the meeting point between ornithology and art, filled with porcelain eggs, "museum" exhibits and sculpture inspired by bird art. The opening event on 5th April at 6pm marks the inauguration of the building as a space for cultural events. On the Saturday at 2pm,Andy and Peter Holden are in conversation - contact Hospitalfield for details.

Andy Holden and Peter Holden: Natural Selection, The Arbroath Courthouse Building, 88 High Street, Arbroath, 01241 656124 www.hospitalfield.org.uk 6 Apr - Thurs - Sat, 11am - 6pm; Sun 11am - 4pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here