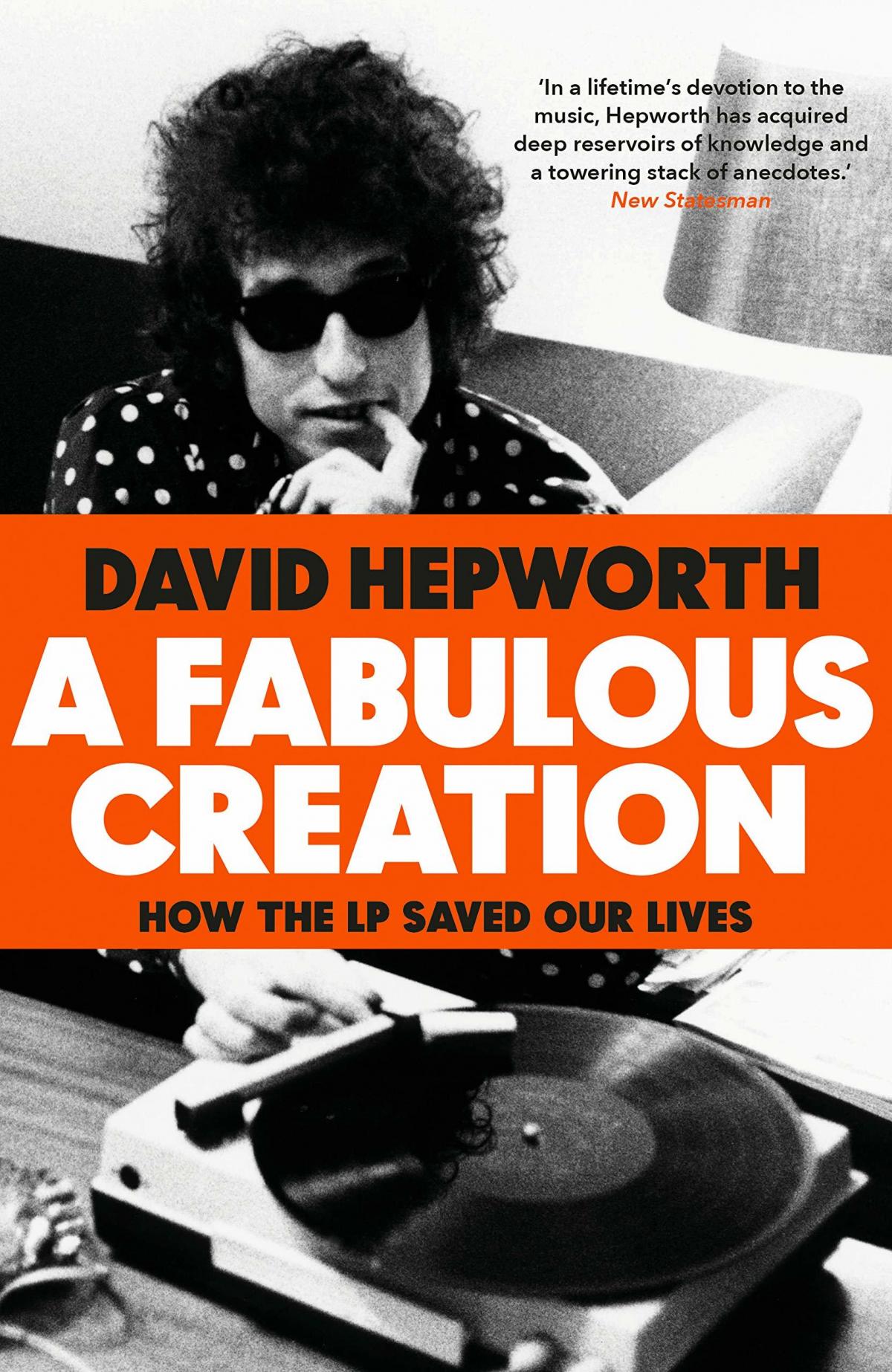

A Fabulous Creation: How The LP Saved Our Lives

David Hepworth, Bantam Press, £20

This isn’t really a book about the long-playing record at all. It’s a book about getting older and being very careful what you wish for. The dedicatees of A Fabulous Creation – that generation of men (mostly) “who knew how it felt to carry an album down the street” – dreamed of a world in which recorded music was bounteously plentiful, cheap, and its carriers indestructible. What they had instead was a slow trickle of long-anticipated releases, each one marketed at a price permanently fixed just outside the range of pocket money, grant or Saturday job, and each one so delicately manufactured that a mere glance, let alone a clumsy girlfriend, could reduce it to a sorry progression of pops, clicks and jumps. (In later years, artists like Christian Marclay would turn the glitches of LP into an artform. To us, a damaged microgroove was a bereavement.)

Now, of course, music is available everywhere, in Alexandrian quantities, albeit in reproduction so compressed it sounds as if it is being broadcast through a gnat’s chuff rather than a Wharfedale Diamond (still the finest speaker that anyone could ever actually buy and take home with them). The young find the idea of paying for music as old-fashioned as spats, while queuing outside a shop in the rain on release day is somehow redolent of wartime or Soviet Russia or Nineteen Eighty Four.

Those of us who crossed over into the Promised Land very often regret we hadn’t died with Moses. The writing had been on the wall for some time. Long before the curse of the box set, “bonus tracks” and “alt takes” of young bands who really believed they had 80 minutes of material worthy of a CD, we had received warnings. The prospect of not just a new album by a favourite band, but a triple! live! album, was once too exciting for words. Then Yessongs came along. That was 1973. May. No one ever played discs two and three. If you ever find a copy in a junk shop, you can check: at least four sides will be pristine black vinyl. Everyone knows that the only triple album that ever worked was George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass and that was only because the most gifted musician in the greatest pop group that ever existed had hung on to all his own best material.

Anyone who puzzles over Hepworth’s dedication clearly wasn’t there. The whole purpose of the LP cover, like the plumage of the bird-of-paradise or the neck-tippet of the great crested grebe, was to attract a mate, or to declare a territory to fellow-males. At one time, my going-out routine was to pat pockets for keys, cash and other essentials and then tuck a copy of A Love Supreme under my left arm, its monochrome profile portrait of John Coltrane intended to suggest that the bearer may not have looked much but was...deep. It usually just got an “Oh...jazz”, always spoken as a descending minor fourth.

Hepworth isn’t anti-jazz, as far as I know, but it’s not his main beat. His moment, as a 17 year-old grammar school boy in the north of England, was 01 June 1967, just five days after the UK release – and a day before the US release – of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which had been previewed on pirate stations and by Kenny Everett a fortnight before the official date. It remains, whatever the exact time you or I or David Hepworth heard it, an epoch in popular music, or – as serious musicologists relieved to be diverted from dodecaphony and Stockhausen for a moment soon announced – music full stop.

It’s an uncontroversial opening, but it bears repeating: Sgt Pepper’s marked the arrival of the LP, not just as a collection of songs, as an art form. Twenty years later, almost to the month, I sat in a North London living room, watching as Lloyd Cole, frontman of the Glasgow-founded Commotions, arranged and rearranged two columns of white cards with song titles on them, trying to find the perfect, Pepperish combination of tracks for Mainstream. (It is the only recording in history to feature both Fourth World trumpeter Jon Hassell and harmonica player Fraser Speirs, a man who was not born, but mined. I wonder how many people listen to it now?)

Hepworth has more insider knowledge and knows more rock anecdotes than any man alive. There is a touch, nonetheless, of Wikipedia research as he stacks up all the things that happened in the world on the day such-and-such was released, and a tendency to end such litanies with a version of “I was that boy soldier” or “That would be me”. But there is no denying that he was there, as writer, broadcaster, record shop owner and above all fan, and no point in criticising him for sharing personal memories, since we all do it. He’s certainly not going to be criticised on grounds of taste. His selections are immaculate and meaningful. Everyone wanted to make another Sgt Pepper’s and then learned they couldn’t. That’s what ultimately drove Brian Wilson (the Beach Boy, not the Labour politician) mad. It defeated the Rolling Stones, who admitted defeat by never playing any of the tracks on Their Satanic Majesties Request again. Ever. And there were those like Leonard Cohen who ceded the point by titling every one of his albums up until New Skin For The Old Ceremony with the word “songs”, just so you knew that the sum wasn’t greater than the parts.

There were, of course, other genre- shaping releases in the womb of time. The title A Fabulous Creation is taken from Roxy Music’s self-titled first album, an object that had as many credits for design and styling as for music. I was disturbed to find I remembered the name of the model (Kari-Ann, I never met you, but I saluted you regularly) on the cover, even before Hepworth told us that she was only paid £30 for reshaping an era. Ever after, there was rock music and there was Roxy Music. They only aspired to be an album band, but were forced to release singles, and to employ more famous (Jerry Hall, Amanda Lear, Marilyn Cole) and expensive models as the years went on.

Later on, albums like Tubular Bells were to suggest new paradigms for rock performance, but at bottom everything was a replay of 1967. Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, however rock snobs seek to denigrate it, was an unimprovable masterpiece, which I never bought but somehow seemed to absorb through my skin. Likewise Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon – I don’t recall whether Hepworth mentions that it only acquired its uncool definite article because artschool duo Medicine Head had already, in 1972, released something called Dark Side of the Moon – which seemed to be part of the air in 1973. I once wandered, a little intoxicated, down every corridor in Edinburgh University’s halls of residence and heard every track on The Dark Side of the Moon at some stage in my moony, stumbly progress. Immersive, or what?

These are unrecoverable moments from an unrecoverable time. These recordings had impact of a zeitgeisty sort that is very difficult to explain to anyone today. The Band’s Music From Big Pink persuaded Eric Clapton to leave Cream, the next biggest band in the world, and go in a different direction. The imminent arrival of The Band in a local shop persuaded one moderately intelligent Scottish teenager (this boy soldier) to stand in the rain with his nose pressed to the window and two 10 shilling notes in his pocket. I bought it, and copped a monster dose of bronchitis for my pains. I still have it, still know every note of side one and almost never play side two because perfection can’t be improved upon. “Vinyl” has made a comeback, but vinyl is a substance. An LP is an experience, and one that can’t and shouldn’t be repeated. The smartest thing about Kanye West is that with The Life of Pablo, a non-album leaked out on various non-physical platforms 50 years after Sgt Pepper, he recognised that.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here