The landscapes of Victoria Crowe tell a story. It's there in the trees – the loss of her son to cancer, the impact of her shepherdess friend and the growing global awareness that nature may be more fragile than we have thought. She reflects on 50 years of painting.

DELICATE, leafless branches spindle across the surface of the paintings in Victoria Crowe’s studio at her home in West Linton – some painted in reddish tones on black, as if made of glowing embers. It’s February, as I visit, and though daffodils bloom in the flowerbeds outside, the trees are wintry, bare-branched, leafless, the kind of sculptural forms she likes so much to paint. “I love winter trees,” she says, “because you can see the structure.”

Trees have been figures in Crowe’s work from her student days. The earliest painting in Fifty Years Of Painting, her upcoming show, and first major retrospective, at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh, is Lone Tree, painted in London's Kingston College Of Art, where she studied. It’s possible to see a journey through her trees, from this solitary, elegant pine, through sturdy, weather-beaten, Pentland trees silhouetted against snow and on to today's more skeletal depictions. That journey is a personal one, coloured by the loss of her son, Ben, to cancer, just as he was reaching adulthood. But it’s also one that reflects the wider relationship of humanity to nature – our increasing awareness of the frailty of our ecosystems.

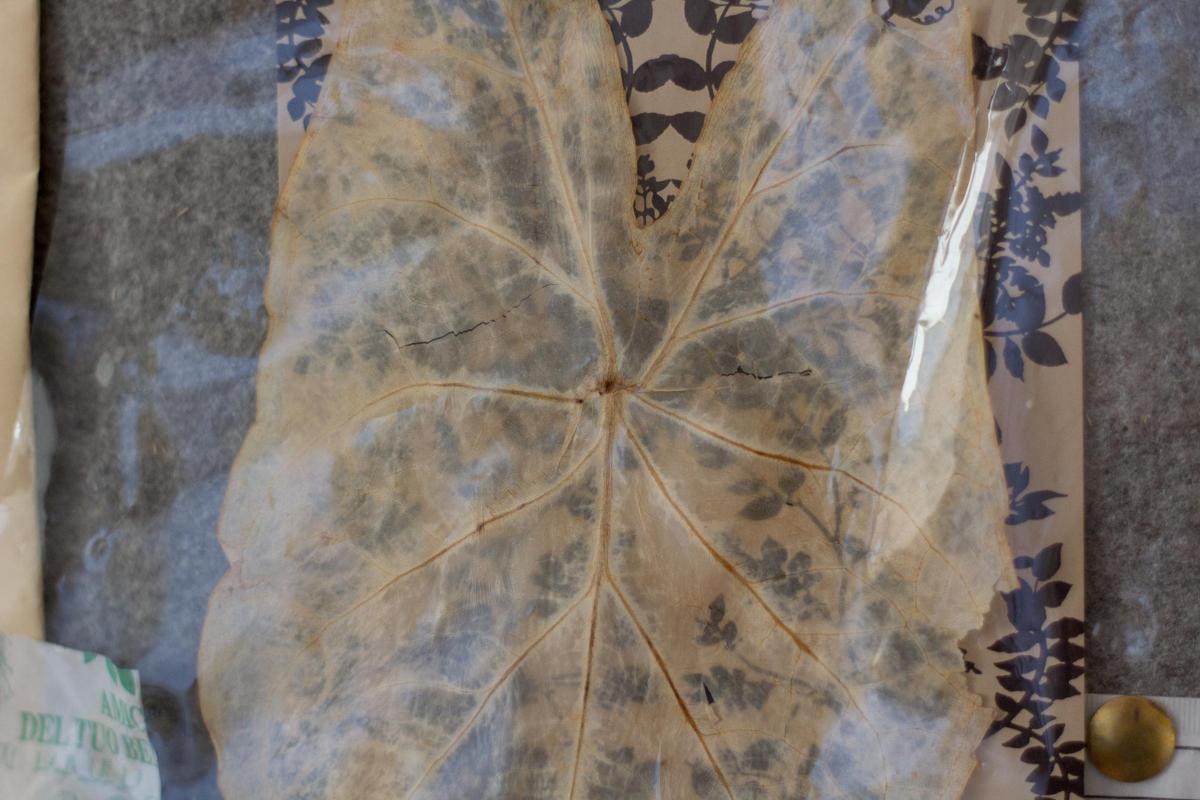

Transience is everywhere you look in her studio. One wall is covered by a kind of thought-board, pinned with fragments from nature – feathers, an almost translucent leaf, a drawing of a dragonfly. It feels like a giant memento mori, a testimony to the impermanence of nature. Look here, or at her paintings, and you can't help but think of her loss.

Crowe, one of Scotland’s finest artists, renowned for her portraits and paintings of nature, had been living in Scotland, and working at Edinburgh College of Art for nearly 25 years when, in 1994, her son, Ben, was diagnosed with oral cancer. He had just left home and was studying psychology at the University of Aberdeen, and he died in December of the following year. “I’d never heard of oral cancer,” Crowe recalls, “especially in young people – they don’t normally get it. He never smoked – apart from the odd fag behind the bike shed. For a long time his doctors were thinking it can’t be oral cancer, it has to be Aids, or something else that might affect younger people.”

During his treatment, Ben attempted to carry on his studies at university. “It was his life,” she says, “and I think there is that thing that as a parent, you just have to let your children go.” On the day she and her husband, Michael Walton, went to Aberdeen to bring him back for Christmas that year, he had a huge haemorrhage, and died. “He never came back,” she says. “And, that changed everything. But I was so lucky that I had like a parallel activity to go to.”

Throughout the period leading up to, and following, her son’s death she threw herself into her painting– and it was then that symbols of impermanence began to emerge most strongly. “All of these things which were previously a subtext for what I was thinking about, became my whole work,” she recalls.

This use of symbolism was “a gift”, she says, that had been given to her by the the pioneering Scottish therapist Winifred Rushforth and one that had already worked its way into her portraits. Crowe had first met the therapist on her 94th birthday and gone on to paint two portraits of her – during a period in which Rushforth was going blind, so didn’t, Crowe says, mind being looked at. She had even attended Rushforth’s dream groups exploring dream symbolism. Her portraits, too – of subjects like RD Laing – increasingly focussed on symbols as a way of conveying the inner-life of her sitters.

“That gift,” she recalls, “meant that I could paint about all that awful year where we didn’t know whether he was going to survive, and then about the time after.” It was a kind of “wisdom” that, she observes, would form a key thread in her own development. “That kind of looking inward at the importance of your inner life, became important – the need to be open to intuition as well.”

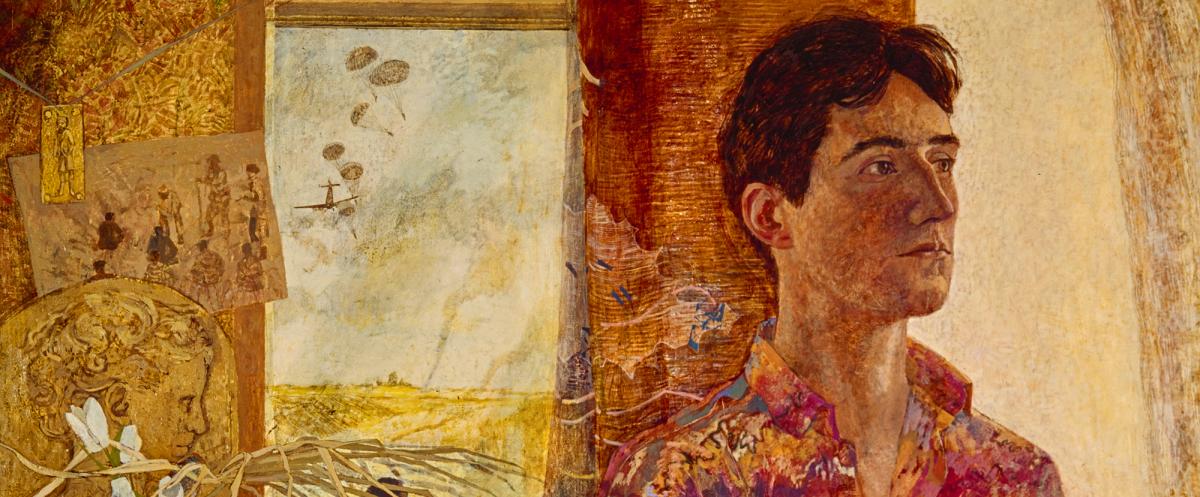

A key, and poignant, portrait of her son, painted prior to his diagnosis, portrayed him standing, boldly in a Beach Boys shirt, next to a window, through which it is possible to see parachutes dropping. “This portrait was painted when the Gulf War was on,” she explains, “and one of his friends was off in the army. But also the army had started dropping parachutes on Kitleyknowe, doing practices I suppose for the war. I used the memory of the parachutes just to underline that sense of the young men possibly having to go off to war. One of the things I think Winifred did for me, was to make me aware of the fragility of a young person – very aware. I also painted him again just before he died but it’s more a sort of a painting of him almost disappearing.”

Amongst Crowe’s most famous paintings, however, are those of the shepherd Jenny Armstrong – painted long before her son’s death and her more symbolic works. Crowe got to know Armstrong, while living at Kittleyknowe, a clachan in the hills, she and her husband Michael, both artists, made their home when they moved to Scotland in 1970.

“We were,” she recalls, “on this high moorland plateau that went from the Lammermuirs to the Pentlands. Fantastic. You could almost do 360 degrees without seeing a manmade object. It was a revelation in all sorts of ways. I’d never seen landscape like this before.”

That landscape, she says, seemed to invite her to paint it. “When the snow was on it, you would get a dotted kind of texture. You should see the shape of the land underneath and it was amazing, because it was just like an abstract painting. It took away the illusion of landscape. It was all up on the picture plane with this kind of texture.”

Within that landscape, she also found Armstrong. “I’d see her every day and gradually she’d sort of intrude a bit more on the landscapes I was painting. She would have been 68, then – she died in 1985.” Armstrong never posed, specifically, for a portrait. Crowe recalls: “I couldn’t say, ‘Sit there, Jenny and I’ll draw you.’ She wouldn’t like that - and I couldn’t take photographs of her. Because it would have been somehow very intrusive if she had been objectified. We were good friends.”

The shepherd’s approach to life had a huge impact on Crowe. “Jenny had such a different kind of knowledge and wisdom and I got courage from that. This way of leaning into the rhythm of life. You can’t rush everything at once, and you have to trust it’s all going to be OK, it’s going to work… We didn’t talk in deep, philosophical terms about it. It was just watching her and her life.”

Crowe glances outside at the crisp blue sky. “She would take advantage of days like this, for example. All the old coats would come out of the cupboard and be hung along the drain pipes to be aired. ‘What a rare day,’ she would say. Yet in the winter when the light was really poor, she would be indoors from 4pm till 10pm next morning and working away inside or sitting inside. So she was very attuned to the natural world.”

The artist only once, she recalls, tried lambing herself. “Once Jenny came to me, because hoggs [young ewes] aren’t supposed to have lambs, because they’re not old enough, but one had. Because my hands were smaller than Jenny’s, she said, ‘Come and help’. So that was the one time I did it.”

At the same time as being submerged in this seemingly remote idyll, Crowe was regularly travelling up the road to Edinburgh to teach at the art college, where she and her husband had taken up positions, and raising her two children, Ben and Gemma. “I was teaching at the art college three days a week, and it was one of those times where you find yourself thinking, 'Can I be artist, wife, mother? Can I keep it all happening? All going?'”

She recalls having at one point been the only pregnant woman at the art college in the painting school. “I think there were about 30 people on the staff, and about three women. And it was a different kind of ethos to what I had learned at art college – which was quite hard but at the same time it gave me an inner strength. I found myself thinking, ‘Actually, does it matter if I don’t fit in? It doesn’t matter.’”

It’s only now, she says, that the impostor syndrome, which she felt over so many decades, has finally shifted. “I have managed to get rid of it partly because you get to this age and you see you’re on this huge journey. You look back and you think, ‘Oh, yes, I was on a journey, I really was on a journey, so it’s all right.’”

As she has been putting together her retrospective, that journey is what she has been reflecting on – as well as the changes in the world around her. She has lived in these parts of the Borders for nearly 50 years and watched changes in the wildlife around. Birds, she says, that were common now seem rarer. “When we were at Kittleyknowe, we used to have curlews and lapwings and oystercatchers. The sound of these birds every spring was just fantastic. You won’t hear them now. I saw one curlew yesterday on the Pentlands. I hadn’t seen one around for ages.”

Most of the books she refers to relate to nature and the environment. In an email following our interview, she recommends Robert Macfarlane’s Underland: A Deep Time Journey. It seems to me that there is a resonance there, since her own work has been about painting the inner life, the underland of her portrait subjects, and its connection to the world around.

Following the death of her son, Crowe channelled her energies into what she describes as the “displacement activity” of painting. Her husband, Michael, however, didn’t have quite the same outlet. Since he was director of first year studies at Edinburgh College of Art, and dealing with young people of around 21 to 22 years old, about the same age as their son at his death, he was finding his job challenging. Crowe observes, “He was having to advise them on their futures,” she says. “He couldn’t do it.” They both took early retirement several years after Ben's death. Michael set up an oral cancer trust to fund research and raise awareness of oral cancer in young people without risk factors.

Crowe and Walton have lived partly in Venice, as well as the Borders. It was a city in which she and Michael, her husband found some refuge after their son died. “I had a studio out there for 14 years and I could still go back to it and access it, though we don’t own it any more. Venice was a place we found incredibly healing after Ben died. When you lose a child you can hardly have conversations with people because they’re so scared that you’re going to cry or drone on about it. They’re worried about their children. It’s like a magic thing. ‘I won’t talk about that. I don’t want my kids to get it.’”

Above all, she says, they could be anonymous there. “Nobody knew our back story. We were just Mike and Vicky. Also Venice itself is a city that is fragile and it’s a city that has survived, so it’s like a metaphor. There is all this potentially incredibly dangerous thing of water and tide and tourism, but it’s surviving. It’s still beautiful. And so that became very, very important.”

Crowe has had her own health problems recently, and observes that the knowledge of what her son went through has put this in perspective. “He had great courage, so will I,” she says. “That’s part of the journey of understanding which the paintings have always been about.”

Her paintings have come back to the landscape – but with a slightly different tone from those early ones. Those trees are different, neither so sturdy-looking, nor so tranquil. Many of her paintings feature nature seen through a Venetian mirror. “Things shift, but I’m probably saying the same sort of things that I said with the Lone Tree,” she says. “Back then I was very into abstract painting so I was thinking about how I could paint it. It was like the icon of the tree.”

How she sees and paints landscapes and nature now, she says is profoundly impacted by two things. “It goes back to Jenny and those [seasonal] rhythms she followed and Ben and that loss. It all gets tied up together.”

The impact of Ben’s death still asserts itself strongly in her work. “I don’t think it does ever go away,” she says. “Although the paintings have come much more back to the landscape they’re never landscapes of tranquillity any more. But that’s not just because of Ben. I think none of us now can look at a landscape and think, ‘Isn’t that lovely?’ You’re so aware of climate change. You’re so aware of the loss of biodiversity of insects and all of these things just kind of disappearing. The landscape to me, when I look at it, seems incredibly fragile, almost apocalyptic.”

Fifty Years Of Painting is at City Art Centre in Edinburgh from 18th May – 13th October

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here