ANKE Kempkes was unaware of Robert Anton before she was approached by gallerist Bette Stoler, one of the late American artist’s closest friends in New York. This was despite the fact that the Warsaw-based independent curator and author had spent much of her working life focusing on performance art and experimental theatre in the 1970s and 1980s. This was the time when Anton was creating his unique table-top styled performances using elaborately carved figurines drawn from observations of the street as well as more magical, Felliniesque creations.

Once Stoler showed Kempkes Anton’s long-forgotten archive of figurines and drawings, Kempkes became captivated by the artist’s singular vision, which saw him feted by New York bohemian society. His insistence that none of his work should be documented, but should be experienced in the flesh by audiences of no more than 18 at a time, meant that few records of his creations exist. Neither are there any scripts, with Anton conjuring up each of his plays from his imagination.

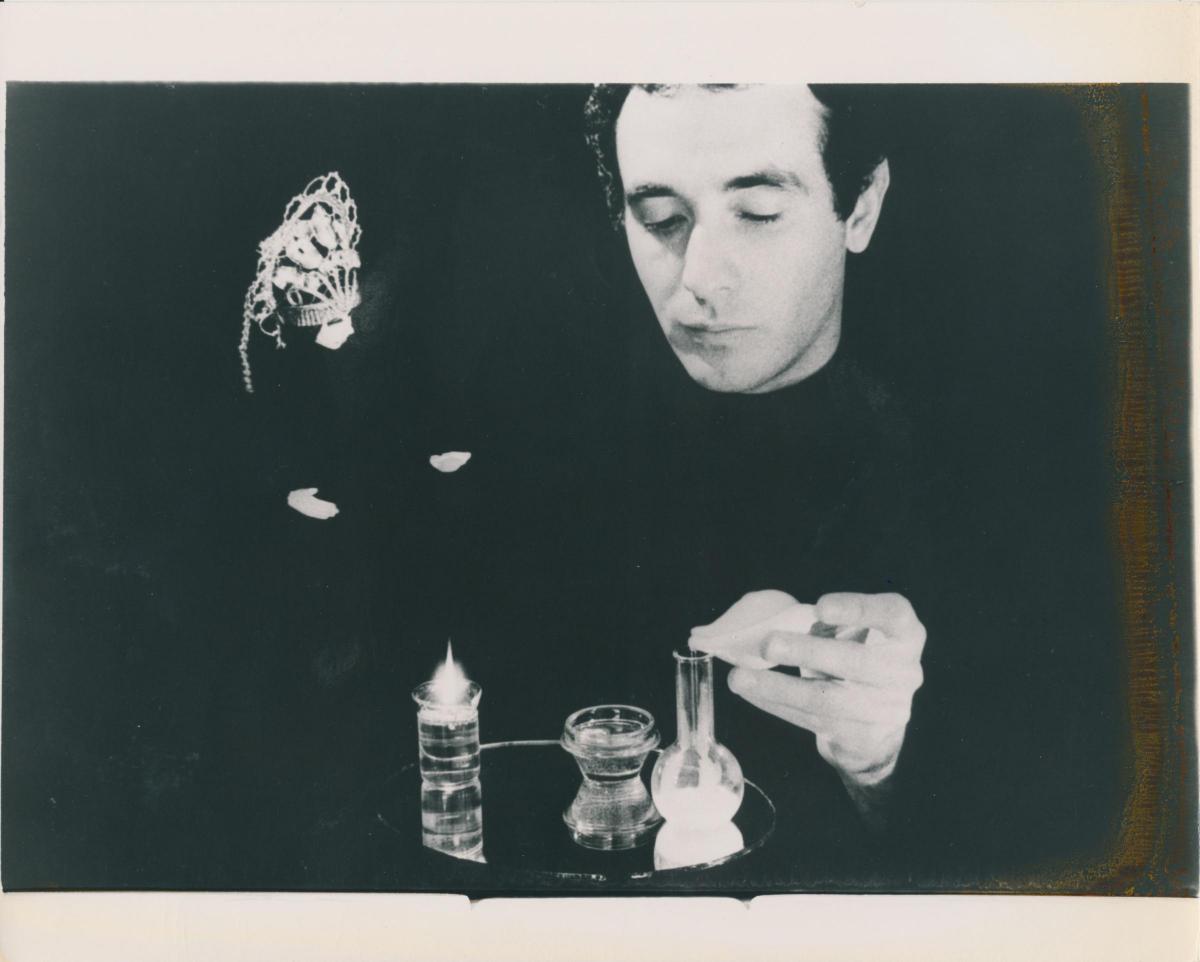

All there was other than the figurines themselves was a fine-detailed description of one of Anton’s works in an edition of American performance periodical, The Drama Review, which also featured a rare photograph of Anton at work. Beyond that was a sometimes conflicting set of memories conjured up by those who witnessed Anton’s work first hand prior to his untimely death from AIDS in 1984. Those who were still around could only speak in hushed tones of an experience that was magical and intense.

The Theatre of Robert Anton brings all this together in an exhibition put together by Kempkes which opens at Tramway in Glasgow this week for the first showing of his work in the UK following versions of the show in New York and Warsaw. Featuring 40 figurines mounted on pedestals alongside props and drawings gathered from Stoler’s archive, the display showcases one of the great missing links of the late 20th century’s New York avant-garde.

“At the time Bette Stoler came to me and showed me her collection,” says Kempkes, “Robert Anton had been completely forgotten in New York. I had to study him myself, and what was unusual was that there was absolutely nothing on the internet about him. This was because when he was alive he insisted on there being absolutely no documentation of his work. He felt that something that was precious about his work got lost if you filmed it.”

As she delved deeper into Anton’s work, Kempkes began to realise why.

“He was very much into surrealism and alchemy,” she says, “and for him it was very important that his work was experienced live. By all accounts that was an incredibly intense experience. There are reports of people fainting, and not being able to breathe.”

Born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1949, Anton began creating miniature theatre shows aged nine, when his parents would take him to see all the Broadway musicals, and he would recreate them from memory, building 18” by 12” stage sets with a sense of detail that saw him compared to Michelangelo.

On arriving in New York in 1970, Anton studied stage and costume design, and in 1973, in collaboration with composer Elizabeth Swados, designed the set for Broadway musical, Elizabeth I. In the same year, Anton began to work with Ellen Stewart’s radical New York theatre troupe, La MaMa. This was as conventional as his work ever became.

In the mid-1970s, Anton presented his work at Robert Wilson’s Byrd Hoffmann Foundation, and toured Europe. In France, culture minister Jacques Lang and President Francois Mitterand allowed him the use of a chateau outside Paris, where he lived and worked for a year, presenting his plays and setting up a visual and mime-based theatre programme for deaf-mute participants.

Encompassing a rich set of influences ranging from Hieronymus Bosch to expressionist artists Otto Dix and George Grosz and the outsiders he saw on the then run-down New York streets, Anton’s work was feted by high society. He attracted fans ranging from Susan Sontag to John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Peter Brook, Broadway legend Hal Prince and fashion world doyenne Diana Vreeland were similarly in thrall to creations which drew from the European avant-garde as much as the American popular culture.

“There is a very specific 1970s sensibility to Anton’s work,’ says Kempkes. “There’s not a tradition of puppet theatre in America as there is in Europe, but he was making his plays at exactly the same time as Tadeusz Kantor was making his Theatre of Death.”

Polish auteur Kantor notably used marionettes in his work, although, unlike Anton’s creations, these were life-size constructions. “In the 1970s, the European theatre festivals were very important to Anton,” says Kempkes.

One of the exhibition’s key components alongside the archival material is a seventy-five-minute film of interviews with some of Anton’s closest friends and fans.

Kempkes says: “We spoke to people close to Anton and they all remembered things slightly differently. It was clear through each person remembering him in their own way that his work had left a life-long mark.”

If he had chosen, Anton could have easily been a commercial success, and was approached by the likes of Walt Disney and Hal Prince, as well as his idol, Fellini. Despite such acclaim, he turned them all down.

“He said he only wanted to create work for the size of the space beneath his parents’ dining room table,” says Kempkes.

Anton’s later work saw him return to the Broadway musicals he grew up with, even as he began to experiment more. Towards the end of his life, his work became more abstract. “The figurines faded out,’ says Kempkes, “and his very last works just used light and colour in a way that came from his studies of alchemy.”

With so little documentation of his work, Anton’s influence is hard to gauge. “There’s no direct line,” says Kempkes. “Because he was diagnosed with AIDS quite early, there’s no notion of legacy-building. Like many artists from the 1960s and 1970s, Anton is so far out of any kind of mediation, and the lack of any kind of documentation makes that really extreme in his case.”

Since The Theatre of Robert Anton was seen in New York and Warsaw, a new generation of artists have looked to him for inspiration. “In Warsaw especially,” says Kempkes, “I see younger artists engaging with Anton’s work as an inspiration, particularly in queer theatre.”

She cites performance duo, Micolaj Sobczak and Nicholas Grafia, choreographer Alex Baczinski-Jenkins, artist activist Kem, and London-based performer Billy Morgan as all falling under Anton’s spell.

“He’s influencing artists more directly now,” she says. “It’s wonderful that something so special can be seen again and have that effect. In the art world now, everything is about being on a big scale and having a big impact, but this is the opposite. This is something much more intimate, and for me Anton’s artwork is all about the imagination. It’s a very active process for the viewer. People can get close to it, and that makes for an intense and emotional experience, and that intensity make it really human.”

The Theatre of Robert Anton, Tramway, Glasgow, Saturday-June 30.

www.tramway.org

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here