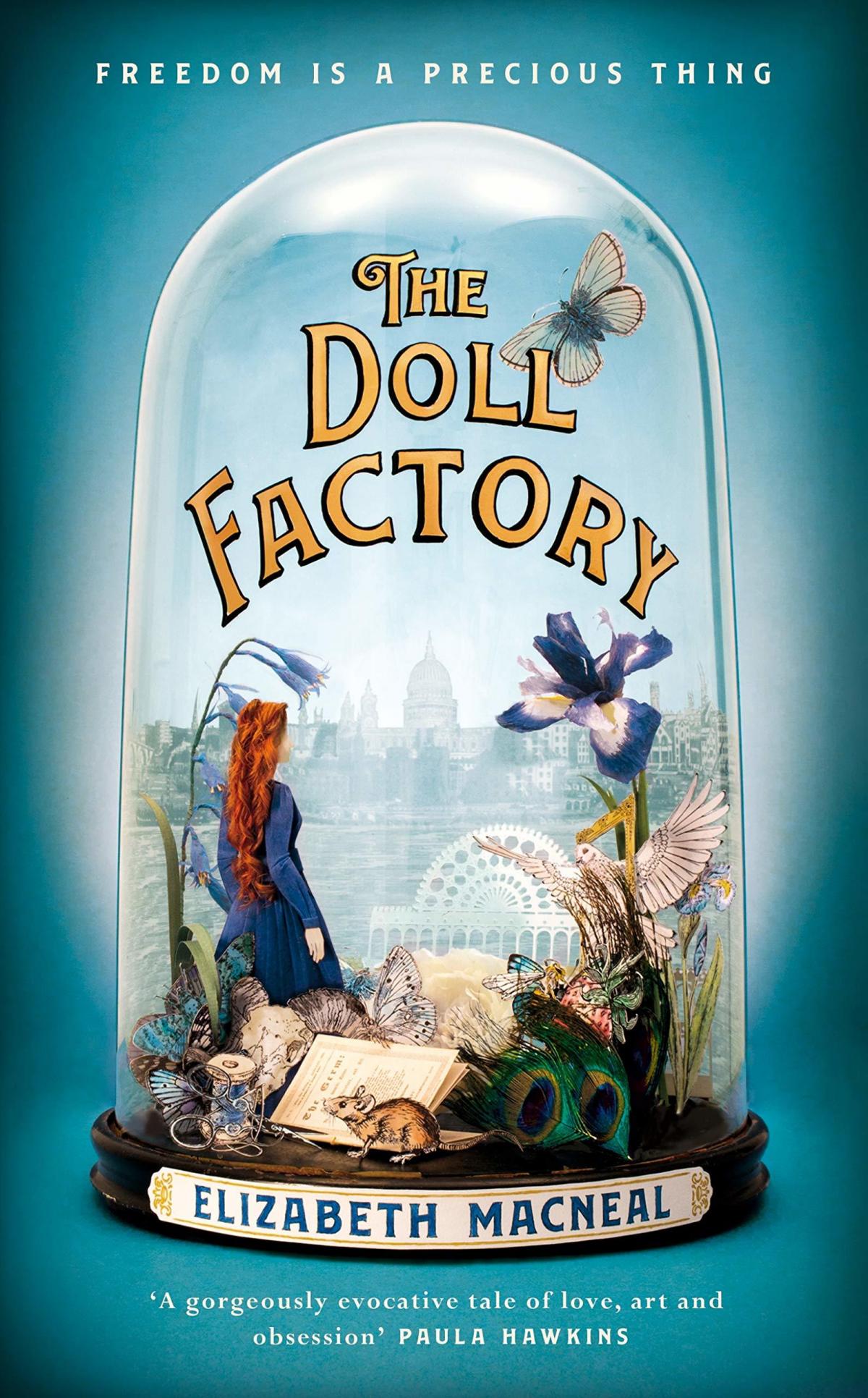

The Doll Factory

Elizabeth Macneal

Picador, £12.99

After reading a few pages of this book, the first from Edinburgh-born Elizabeth Macneal, I concluded the title and cover were the central elements of a conspiracy. They had worked together to perform an act of deception by creating certain expectations that were quickly, filthily and uncompromisingly dispelled. But, as I came to realise, this is a book about things being something other than they appear to be, quite often the exact opposite. That which looks free is trapped. That which seems fresh is rotten. Sometimes, that which is alive is dead, it just doesn’t know it yet.

The Doll Factory is told from the perspective of three characters. The first is Iris Whittle, a young lady working long hours in a doll shop run by a hallucinating laudanum addict who maintains discipline, and a prevailing sense of unhappiness, by cruelly pinching the soft inner sides of her girls’ elbows. Iris works silently alongside her twin sister, Rose, whose beauty was destroyed by smallpox at great cost to her confidence. But Iris wants more than the factory and the path seemingly laid for her by convention – she wants to paint and live the sort of life that would allow her to do so.

At the expense of her relationship with her sister, she is drawn into a group of pre-Raphaelite painters by Louis Frost, so that she might serve as his model in return for lessons. For Iris, the moral ambiguity around her status, at a time when social freedom for women is severely restricted, is only just outweighed by the prospect of realising her passionately held desire to become a painter.

If Louis is not exactly the embodiment of a dream, then he at least offers her the promise of a dream coming true. His intentions are initially ambiguous, and it seems as though his offer to teach Iris is equal parts gesture of goodwill and ego flattery. He never becomes an entirely likeable character, despite being seen almost exclusively through her eyes. When it becomes clear he is cultivating a talent he didn’t anticipate, he tries to frustrate her development by withholding praise and then by other, more serious, means. As one of his associates remarks, “she’ll be snapping at our heels if we aren’t careful.” Nonetheless, their relationship gradually becomes romantic and different types of love become powerful joined for Iris. “Where,” she wonders, “did wanting to paint end and wanting Louis begin?”

For the first time, she is afraid of death, a simple realisation that speaks to the limits of her previous life and the potency of her attachment to Louis, her liberator from what went before. Macneal wisely chooses to make this a prolonged process to remind us of the determined caution that Iris sees as the only means of freeing herself from the cloying norms to which she is expected to adhere. And yet there is sense of disquiet that the relationship between Iris and Louis is no more equal for the addition of romance. Indeed, it only adds another layer of potential deceit. The reader is easily brought into sympathy with Iris on realising she is the partner for whom the relationship poses the greatest risk, but the one without a full understanding of the elements in play.

There is another threat lurking unknown to Iris and Louis in the form of Silas Reed, a collector of curiosities – he stuffs animals – and insecure fantasist. He is certain the greatness of his work will one day be recognised, bitter from believing the recognition should have happened yesterday. A brief introduction to Iris is enough to start a terrible obsession. Soon he is following her through the streets of London and fantasising about a relationship. When he realises Iris doesn’t even remember him, she becomes something to be captured and controlled. In different ways, Iris and Silas try to make real what is imagined.

The jumps in Silas’s thinking, the sudden deterioration of his emotional outlook and failure to comprehend the world he inhabits, all stand in contrast to Iris. Macneal is a skilled sower of bad seeds. As the story develops, it becomes clear that Silas hasn’t been brought to the verge of madness by his obsession with Iris, rather the obsession has grown out of an existing mental state. Iris might not be his first victim, but Silas is unsure about things he has done in the past, such is the severity of his mental disorientation.

Even still, some readers might wonder at the extent of the turmoil unleashed by an inconsequential encounter. Bestowing madness on a character gives certain automatic advantages to an author. There isn’t the same need to account for behavioural changes and the unpredictability is inherently dramatic. In this case, there is the added thrill that comes from contemplating the potential actions of an individual operating outside the bounds of a society that already seems degraded when compared with our own. If there are questions of believability, they relate less to the actions of Silas than to the time it takes Iris and Louis to recognise the danger. In fact, they fail to understand entirely until it hits them on the head. Albie, a young street boy known to both Iris and Silas and the final character given perspective in the novel, is the one person who properly understands the threat. At the crucial moment, however, he is prevented from alerting Iris by a development that, while consistent with the life he lives live, feels a little cheap when set against the novel’s otherwise patient accumulation of tension and unease. That is, it feels too easy, too obvious, too done-a-thousand-times-before.

This misjudgement is untypical. More worthy of comment is the discipline with which Macneal maintains an authentic mode of reference – every literary touch is matched to the novel’s setting. And it’s disgusting! The book froths with horrible food, putrid smells, dirty people and rotting animals. It would be easy to describe this attitude as uncompromising, but that would be to convey a misrepresentation: Macneal revels in little moments such as a robin “singing in a heap of chicken bones”. Everywhere, innocence is spoiled. One scene, involving baby mice, almost had my eyes running about on the table. With most of the book’s weight in my left hand, I wanted to be able to read faster, not so it was finished but so I could reach the end. Macneal makes it so Iris’s fate is uncertain until almost the last page and, given the darkness of the whole, no easy presumptions can be made. But I knew I was making my way through the final pages of a memorable book.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here