Walking into the stable yard at Jupiter Artland a few days before the outdoor sculpture park opens its doors to the public for its annual summer season, is a little, I imagine, like stepping into the past. There, piled up high against the old stable building, which now houses two art galleries, is a towering compost pile, sloping like some ancient ruin and heating up nicely amidst its straw bale insulation. Its pungent farmy smell somehow seems to suggest that it’s all very well for visitors to swan around looking at art, but in nature, there’s work to be done.

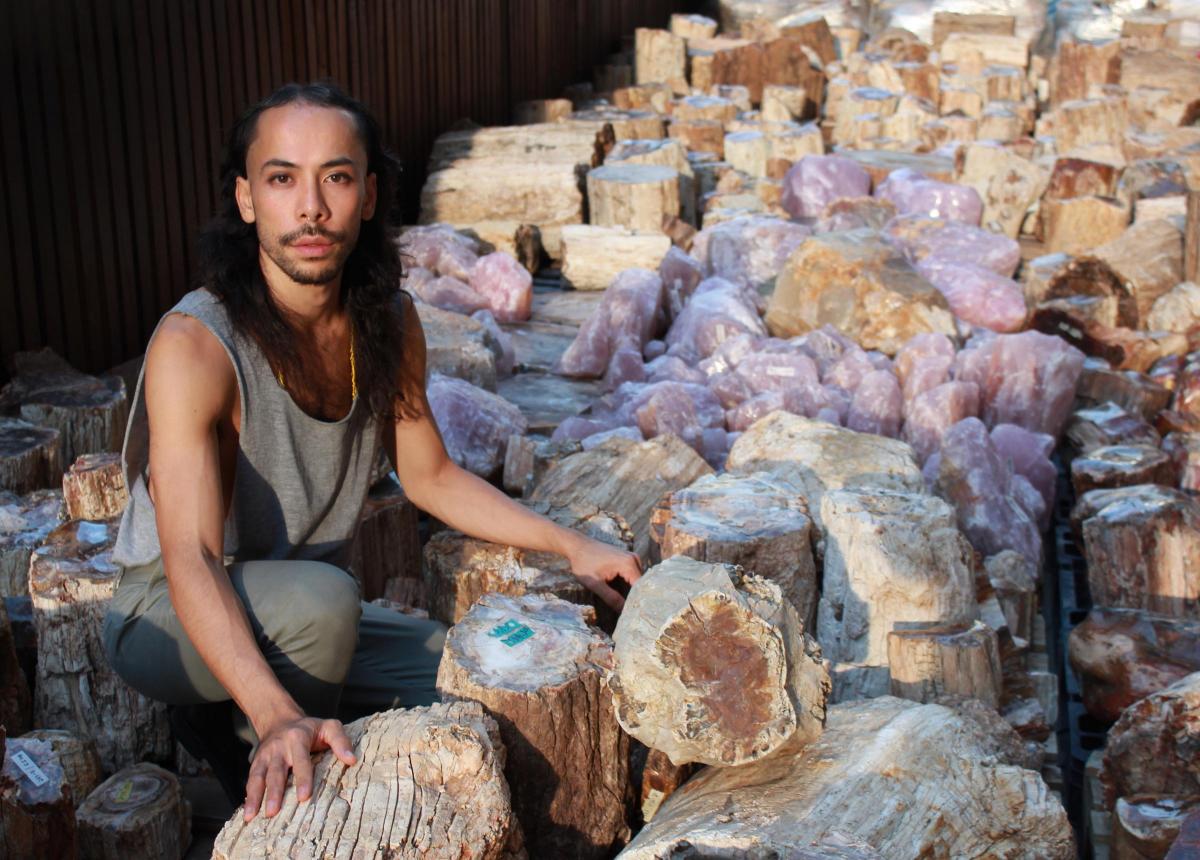

And it is the organisms doing the work that are of interest to the artist who has created this mega-heap, the innovative young Brazilian sculptor Daniel Lie, who opens Jupiter’s summer season with a solo show comprised of five monumental installations dotted around the Jupiter space. We meet, far from the stench, in the temporary site office buildings, as Lie takes a break from trying to hook up two old telegraph poles with hangmen’s knots.

Lie’s practice is wide-ranging, globally-so, concerned as it is with the fundamentals of life and death through the prisms of archaeology, science, gender, colonisation and decolonisation, spirituality, power structures and mycology (the study of fungi) amongst other things. And yet the materials of the space in which Lie is working are at the centre of the work. The artist, who is non-binary, has spent the past two years researching this exhibition alongside Claire Feeley, Head of Exhibitions at Jupiter, involving experts from local institutions and organisations, visiting local archaeological sites, drawing parallels with other world cultures. Previous exhibitions have included “Death Centre for the Living”, Vienna Festwochen, (2017), which gave the semblance of ritual to its natural components and “Children of the End” in Sao Paolo (2017). The expression is through earth materials, biodegradable often, and wilfully so, Lie’s theatrical exhibits displaying a sense of ritual, often decaying daily as the exhibition run progresses. But there is always growth, too, and mycology is key, Lie says, eyes wide, telling me of the mycologist from Edinburgh University who the artist contacted to help uncover the vast microscopic detail of Jupiter’s fungal life. Ranging beneath our feet, Lie points out, are the fungi that interconnect tree roots and plant life, miles of mycelium in every square inch of soil, the white roots by which plants “talk” to each other.

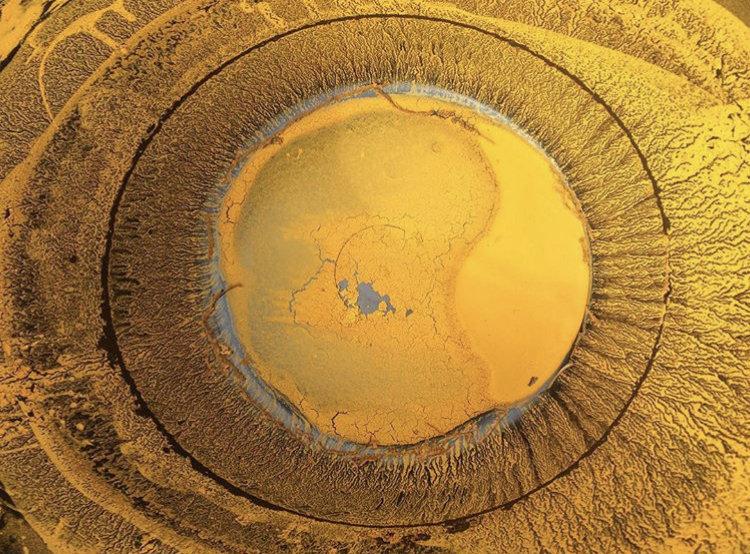

They are there, too, in the stable gallery, heated via elaborate copper pipes and a heat exchnage system in the compost heap outside. The heat, in its turn, aids the growth of the pink oyster mushrooms and other “unnamed entities” that are embedded in the unglazed terracotta pots hanging ceremonially from the ceiling on jute ropes waiting their fungal “bloom”, or the giant plastic-wrap tubes stuffed with damp straw from which pink frills of mushrooms are just starting to burst. The room is dramatic, even in this semi-prepared state, with the air of some archaeological discovery brought to life, a ritual burial chamber or store room, the walls painted with turmeric. Lie visited Cairnpapple’s neolithic henge monument as research for the exhibition, struck by the connection with Brazilian archaeological burials. The title, “Quing”, is the word for a non-gendered or ambiguously gendered monarch, for fungi, themselves, have quite literally thousands of sexes.

In the Dovecot, its interior filled with stone ledges on which doves would have perched, small unglazed ceramic pots ferment, neatly tied with jute string and cotton lids, filled with the same rice, water, sugar and spice mixture which Daniel has used in the stable gallery. It’s like walking into a catacomb of living things, the ghosts of the former inhabitants a veil over each recess.

So, too, with “To Mourn the Living” in the upper stable gallery, jute sacks saturated with earth and sprouting linseeds counterbalancing a vast hemp rope of flowers, tied on, a giant hawser which goes out of the window and is tethered to a low wall nearby. Lie’s work is full of this sense of counterbalance: of counterweights, suspensions, everything carefully knotted, skilfully assembled.

More dying flowers in the suspended “The Others’ Privacy” in the ballroom, draping on a floor lined with wool from the estate’s animals. Two of Lie’s Brazilian colleagues are creating a soundworld for this room, the windows blacked-out. The exhibition is non-verbal, Lie tells me. You must take it in with your senses.

As I leave, Lie is back up a telegraph pole laced with the stems of dead ivy, taken from the estate woods in which witches were once burnt, wrangling ropes, neutering the death-noose. There is a great thoughtfulness in this work, a sense of what links us all, no matter how we define ourselves, a sense of what is human delivered through what is not human, a sense, too, of our own insignificance. If you can, go now, then go again in a few weeks, and see how the process of growth versus decay pans out over the summer.

The Negative Years: Daniel Lie, Jupiter Artland, Bonnington House Steadings, Near Wilkieston, 01506 889900 www.jupiterartland.org, Until 14 July, Daily 10am - 5pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here