BRAM Stoker, the Irish author of Dracula, has been with Joseph O’Connor almost all his life.

“I was maybe six or seven years-old when I first encountered him,” says the award-laden Dublin-born novelist, recalling glorious summer weekends with both sets of his grandparents, who were neighbours in the suburb of Crumlin.

Now an international best-selling author, O’Connor, 55, is reminiscing fondly about his maternal grandmother. Catherine O’Grady was “skittish and playful,” instilling in him a passion for spooky stories on those pleasure-filled visits. The result is his latest novel, the gorgeously dark Shadowplay, which tells the rich, Dickensian story behind the creation of Dracula. Set against the backdrop of the Ripper murders, the trial of Oscar Wilde and the building of the Titanic, it spans the decades from the 1880s to Stoker’s death in 1912.

Join The Herald Book Club here

“Granny had a great love for the drama of ghostly tales set in the rural Ireland of her childhood, as well as the grand stately homes of England and, of course, Dublin.” His favourite included a relative who, in Dublin slang, was a glimmerman – a lamplighter – on his rounds in a poor part of the city near St Michan’s Church one night in the 1880s.

“In the crypt there are mummified bodies from the 11th and 12th centuries, which some archaeological trick of the soil preserved and which people would visit. On this night, he notices a prosperous-looking, athletic young man gazing up at the church steeple. He thinks this well-dressed man is lost so they begin to chat. The man tells him he’s interested in the mummies. They shake hands; they exchange names. He says he’s Abraham Stoker and that he works for the government in Dublin Castle and occasionally writes ghost stories.”

In Shadowplay, Stoker encounters a St Michan’s mummy – “a ghoul clambering wearily from his box, hair floor-long, raven’s nest in his ribcage” – in that crypt reeking of “rotted coffin.”

Over tea in London's west end after own ghost tour, O'Connor expands.“I remember excitedly telling my parents that Granny's relative had met this famous author when he was alive. ‘And maybe a few times when he was dead too...’ she said, leading me to believe that on the occasional foggy night many years after he had died, Bram Stoker could still be seen in that church doorway."

In sparkling sunshine rather than a filthy fog, we rendezvous on the Wellington Street steps of the splendid Lyceum Theatre, the setting for much of O’Connor’s atmospheric book, where I ask him to conjure up the shades of Shadowplay’s dramatic trio of protagonists: the great actor-manager, Sir Henry Irving, his divine leading lady, Ellen Terry, and theatre manager, one Bram Stoker. We walk around to the Exeter Street stage door. Online, notes O’Connor, you can find the only known photograph of Irving and Stoker together, exiting that door, about to climb into a carriage. “The photographer must have stood exactly where we are,” he says, pointing to a bowler-hatted Chaplinesque chap bustling between the two great men, blissfully unaware of his brush with Victorian celebrity.

Join The Herald Book Club here

Around the corner on Burleigh Street, the surnames of Terry, Stoker and Irving are engraved on the theatre’s exterior wall, “a stark memorial to three remarkable artists.” Now the den of the long-running musical The Lion King, the Lyceum will not allow us inside to explore the legendary theatre, which O’Connor describes in his novel as being haunted by the ghost of a young girl called Mina – one of many allusions to Dracula – so we imagine instead how much Irving would have loved this show.

“He adored spectacle, and he would have relished playing the Lion King himself,” says O’Connor, adding that Ellen Terry’s ghost is also reputed to haunt Edinburgh’s Lyceum Theatre, one of many she acted in and where her phantom allegedly still walks in the "ghost light", the electric light always left on stage when a theatre is empty so that it is never dark. In Stoker’s day, it was a candle, explains O’Connor, whose novel, Ghost Light (2010), also has a theatrical backdrop, telling of the love story of another doomed Irish genius, JM Synge, and the Irish actress Maire O’Neill.

Join The Herald Book Club here

With his wife, the film and TV writer Anne-Marie Casey, Dublin-based O’Connor has two teenage sons, one of whom has acting ambitions. “God help us,” sighs his father, who comes from a creative family. His siblings include artists and musicians, including the controversial singer Sinéad, while their father, Sean, wrote the bestselling memoir, Growing Up So High.

How old was O’Connor when he first read Dracula?

“I was about 12 and I was absolutely captivated," explains. "It’s almost like a pilgrimage to me. I read it every three or four years. I always see something new in it. It’s been a very influential book for me. My 2003 novel Star of the Sea is told in the same form. Stoker gave me the idea to tell a story in different voices and registers. Dracula has diary entries, letters, notes dictated in shorthand. From him, I realised that if a book is going to be long, one way to inject energy into it is to vary the tone of the storytelling, using first and third-person narrative. Genre-busting, if you like.

“A theme of Shadowplay is how everybody contains other people, how we see ourselves in the first and third person – there’s a line in the book when Ellen Terry says ‘everyone is acting, almost all the time.’ Secretly, I think that is why we read. When we encounter a character that we love, it might be that we are encountering something about us. To me that’s at the heart of the writing and reading experience. It answers some deep need in us and it’s probably why I began writing in my teens, filling copybooks with dreadful gothic pastiche.”

He has been trying to write about the “bromance” between Stoker and Henry Irving for a while. “It never worked, then the day came when I put Ellen Terry, who was the first big star, into the book. There was suddenly this crackle of electricity and I knew what was missing: the noise of her smart, witty version of events banging against the two lads’ versions. That produced a spark of great energy. She is, of course, also one of the few real people mentioned in Dracula, a byword for beauty and accomplishment.”

Stoker’s story is sad: a troubled marriage, conflicted over his sexuality and a writing career that never worked out. He never saw his book’s success, although his formidable wife Florence fought and won rights of ownership, establishing principles of copyright after his death. (“All authors owe her a debt of gratitude”, remarks O'Connor)

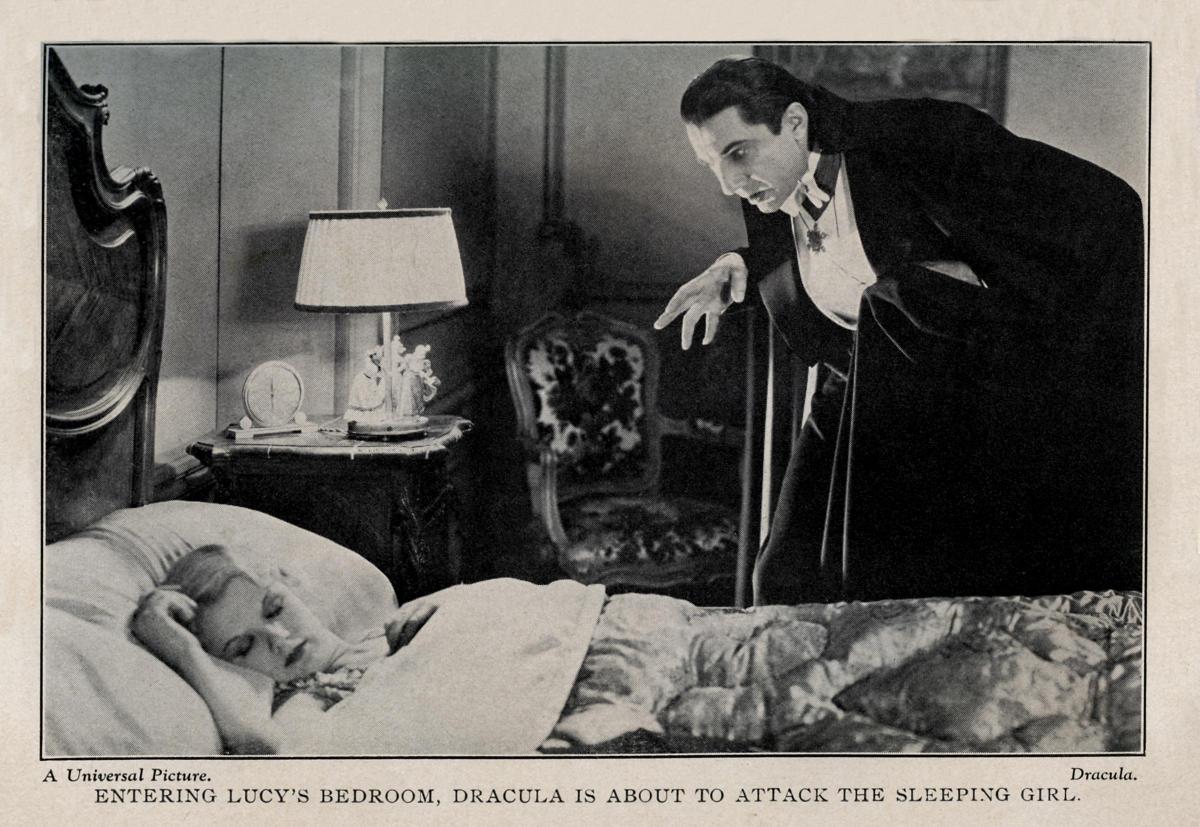

“The biggest irony of them all is that as readers we have a key piece of information none of the characters in the book has. We want to say to Stoker that pantomime thing, ‘Look behind you!’ For Dracula has sold tens of millions of copies and been filmed 200 times – there have been operas, ballets, television adaptations, manga and anime versions, comic books, video games. Stoker would have been astounded by the immortality of his character.”

Finally, I ask O’Connor, currently Frank McCourt Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Limerick, if he gets nervous on publication. “I’ve done it nine times now so I feel calm. I really enjoyed writing this book, despite the many late nights and the challenge to make something as brittle as the English language work while always thinking of the reader. I am proud of it,”.

He has every reason to be proud. Shadowplay is an accomplished, compelling read that gave this reader late nights, too. It's author, however, jokes that his subject might not be so enthusiastic.

“Bram Stoker may be waiting on the other side, preparing to drive a stake through my heart.”

Shadowplay, by Joseph O’Connor, is published by Harvill Secker, priced £14.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here