“F****** hell,” says Danny Boyle, sitting back in his seat in a plush Edinburgh hotel and sighing loudly. “I hope they don’t try and claim some ownership of it”.

The expletive and the long exhalation of breath are the 62-year-old director’s response to my suggestion that he may inadvertently have produced the feelgood Brexit movie of 2019. “They” are the politicians and citizens whose decision to vote Leave in the EU referendum appeared to come in part from a sense of nostalgia for a time when Britain was, well, Great. “It” is Boyle’s new rom-com, Yesterday, which aims to do for The Beatles’ back catalogue what Mamma Mia, Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketman have done for those of ABBA, Queen and Elton John. So is Yesterday the film to make Brexiteers misty-eyed for a time when the UK mattered, at least in terms of the rock and pop music it gifted the planet? Like he says, he hopes not.

Behind the hope lies a certainty of sorts. The Beatles, he reminds me, were outward looking kids from an outward looking city who journeyed to the US and immediately took a political stand by refusing to play in front of segregated audiences. “I love them for that,” he says. And although there’s a sense of nostalgia in their work it’s cut with too much melancholy for it to be sentimental, he thinks. “Their work is not to be thought of as being about Little England. I think it does have a haunting connection with something about us that is being lost … but I think it’s more to do with Liverpool, because when they were coming out Liverpool was in the beginnings of its decline as a port town”. So no, he doesn’t think he’s made the feelgood Brexit movie of 2019.

Boyle, for the record, voted Remain in 2016, at least according to a list published in The New Statesman (and he doesn’t say otherwise when I mention it). On the same list is his friend and Yesterday screenwriter Richard Curtis, who also happens to be “a Beatles nut” (Boyle’s description). “I have a healthy love of The Beatles,” the director adds, “but his is just not very healthy at all”.

Despite that, Yesterday isn’t primarily an exercise in fan boy nostalgia. It isn’t a biopic, either, or an adaptation of a stage musical. It’s cleverer than that. And weirder.

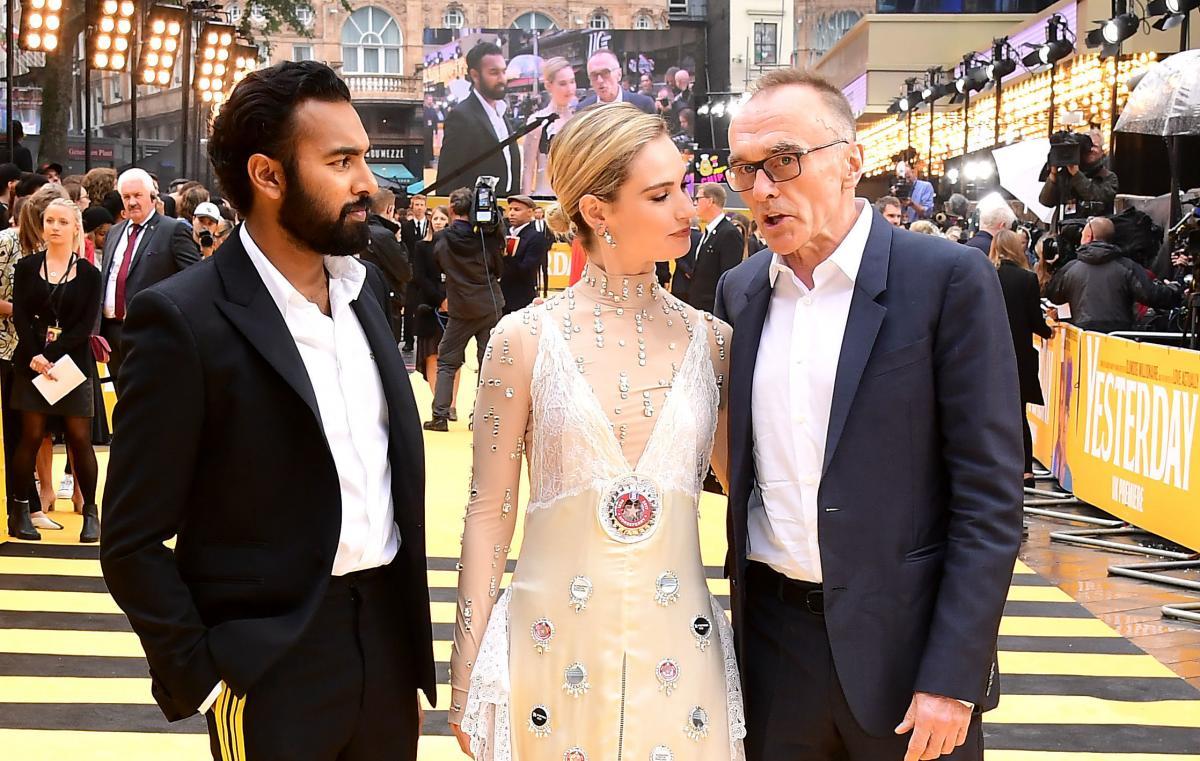

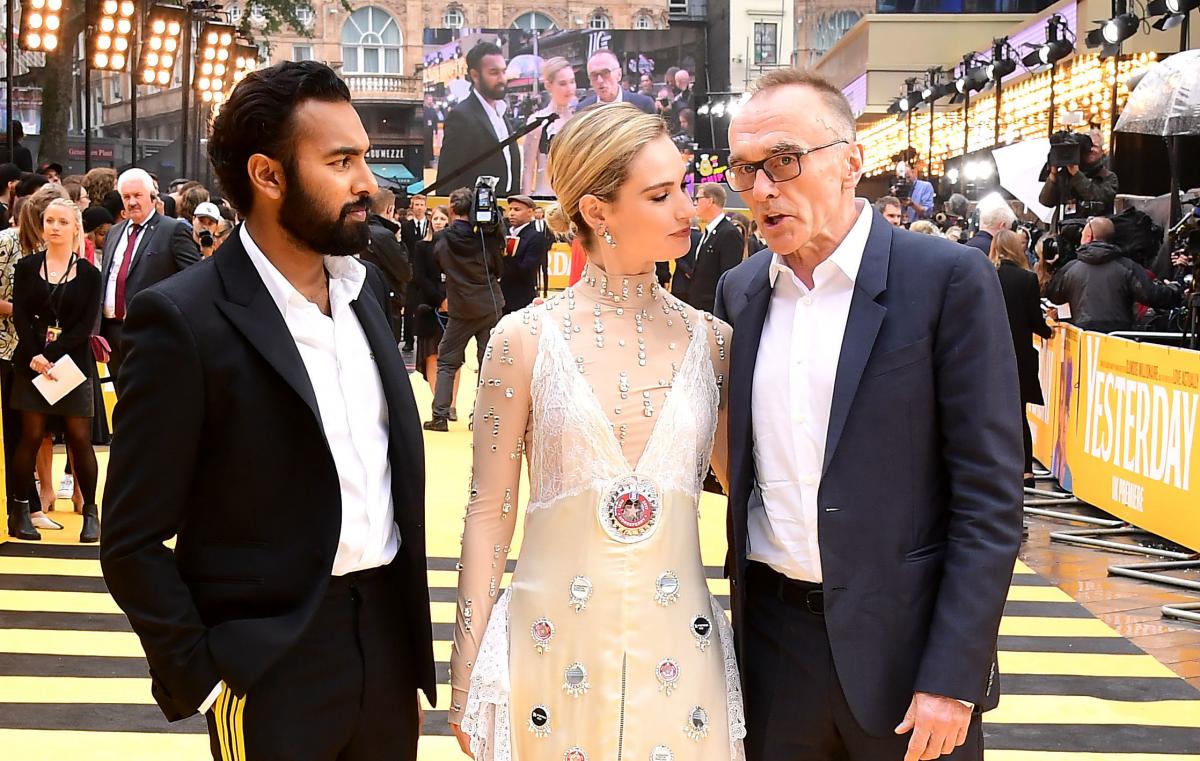

The starting point is an unexplained event which blacks out the planet for 12 seconds and causes everyone to forget The Beatles and their music – everyone except aspiring 27-year-old singer songwriter Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), who decides to capitalise on the fact by passing off their songs as his own and reaping the inevitable rewards. First comes a support slot with Ed Sheeran followed by a million dollar record deal with unscrupulous American manager Debra Hammer (Saturday Night Live’s Kate McKinnon). Pretty soon, Jack has the ear of the world.

Sheeran wasn’t the first choice for the rock star cameo part – Curtis wanted Coldplay’s Chris Martin – but he makes a decent fist of the role. Boyle impressed on him the need to rehearse with the other members of the cast, “to get the rhythm of the piece”. Sheeran was happy to oblige. “I think he quite liked being with a bunch of bitchy actors,” says Boyle.

Trailing in Jack’s wake is devoted former manager and childhood friend Ellie Appleton (Lily James), now a teacher at the local high school. She provides the “rom” side of the “rom-com” equation.

Dig deeper, however, and the film’s premise raises interesting questions. One is whether a 27-year-old Millennial would even know that many Beatles songs. Think he would? There’s a whole sub-genre of YouTube videos which says he wouldn’t. In them young people, mostly American and mostly male, are played a classic rock track for the first time and their response to it is filmed. The Beatles feature a lot. So if Yesterday isn’t based on a crazy What If? proposition, is it actually based on the opposite idea: an assumption that people really are forgetting about The Beatles even as they hold onto the music of ABBA, say, or Queen?

READ MORE: Sir Paul McCartney on his late wife Linda's photography ahead of Glasgow exhibition

“Though they’d never admit it, I’m sure that was part of Apple Corps’ philosophy in licensing us the songs – to try to make them appeal to a younger generation, to keep the catalogue alive, really, in the playlist era,” says Boyle. “But I think the instinct to refresh them isn’t a panicky one, it’s a natural one.”

He also thinks that the extensive permissions granted – the deal with Apple Corps allowed the film-makers to use between 15 and 18 songs from the canon, with nothing off limits – and the fact that permission was given at all shows the surviving Beatles to be relaxed about their own legacy and confident that they, like Jack, still have the world’s ear.

“They agreed to this, which is an unusual vehicle for the work of a group because at the moment the fashion is obviously for a biopic, a life story, a direct, obvious vehicle for the story of the songs. Or a karaoke kind of an event which leads to a stage musical or comes from a stage musical. But if you think about it this is a very good illustration of their sense of humour. They have licenced these songs – and they don’t license a lot – to a film which imagines them being erased from the consciousness of the world. That’s very funny.”

Boyle, too, is relaxed about The Beatles’ musical legacy and their cultural staying power. “My own work will slide off long before theirs,” he says. “I have this rather, like, pretentious theory that they are part of us, anyway. That culture is a part of us and it will be quantified and captured at some point so we carry it. It’s not something out here that’s introduced to us, on some level. We carry it in some way.”

As proof he points to the number of plays the Fab Four had on streaming platforms in 2018, a tolerably big year in Beatle-land (the 50th anniversary of the release of The White Album rolled round) but nothing special. And the figure? Three billion. “That’s incredible. So there’s either a lot of old timers who have picked up on Spotify or it does have some appeal to the young.”

If it’s the former, it begs another question: who does Boyle think is going to watch Yesterday? Sure, the film’s hero is a 27-year-old but it’s hard not to see Jack as simply a proxy for the film’s likely audience – those, like Boyle and Curtis, who are on or around that very Beatles-y age of 64.

“Yeah, you could certainly argue that,” the director admits. “Working Title [the production company] and Universal [the studio] would prefer you not to make a big case for it, because they’ll be trying to get a younger generation in to watch it.”

His own film aside, how does he view the wider health of the industry? Currently 15-24-year-olds make up the largest proportion of British cinema audiences but that youthful enthusiasm is fuelled largely by American blockbusters such as superhero movie Black Panther. Independent films – and Yesterday is one, in spirit at least – are more popular with the over-45s but unlikely to gross Marvel-style millions at the box office.

“There’s no doubt that cinema is in trouble,” he says. “It’s not that there aren’t very successful films – the figures tell you those Marvel movies are phenomenally successful – but it’s quite a narrow corridor and that’s very worrying. Because if that closes for some reason, if it drops off the edge of a cliff like Westerns did, then there’ll be problems.”

One of the reasons for cinema’s malaise, he thinks, is that “everyone is fleeing to long-form television, which is a much more private way of experiencing story-telling and one based on a very different time contract whereas cinema’s unique in that it's a very exclusive time contract”.

READ MORE: Alison Rowat's review of the film Yesterday

Cinema has reacted to the threat either by creating big “event” movies or, increasingly, by turning to music. Blinded By The Light, a film featuring the music of Bruce Springsteen, is out next month. Next year sees the release of The Power Of Love, a Celine Dion biopic. Also in the offing are biopics of (among others) David Bowie and Keith Moon. “It’s not just nostalgia, which some people argue it is because we’re in such uncertain times, it’s just cinema reacting to what will work,” says Boyle. “What will give people a blast of a communal experience where they give you their exclusive time”.

Of course Yesterday isn’t Boyle’s first brush with The Beatles. Along with the National Health Service, the BBC, the Jarrow Marchers and the Empire Windrush he hymned the band and their achievements in Isles Of Wonder, his opening ceremony for the 2012 London Olympics. Paul McCartney closed the spectacle but not before Arctic Monkeys’ Alex Turner had performed a rousing version of Come Together. “I asked him to choose a Beatles song and he picked that one,” says Boyle. “He said it’s impossible to learn. Literally impossible.”

I sense that the making of Yesterday has caused Boyle to reflect some on that celebrated Olympic ceremony and its optimistic view of a pluralist and communitarian UK. Not for nothing was it written off by Conservative backbencher Aidan Burley as “leftie multicultural crap”. Audiences, it seems, have been in equally reflective mood.

“It’s interesting that watching the film a lot of people say ‘What has happened to us since 2012? What has happened to this land and will it return?’,” says Boyle. “My argument is that yes it will because these things ebb and flow.”

As fate would have it, UK culture secretary at the time of the London Olympics was Jeremy Hunt while the London mayor tasked with delivering the Games was one Boris Johnson, now Hunt’s rival for the leadership of the Conservative Party and currently the favourite. What did Boyle make of the man who may well be our next Prime Minister?

“I’m not getting drawn,” he says.

Oh go on …

“That lot? Absolutely not. But we worked very hard to do what we wanted to do.” And that, it seems, is the end of the matter.

Boyle is only slightly less tight-lipped on the subject of a third Trainspotting film. A well-received 2017 sequel to the seminal 1996 film proved that the appetite for another chapter in the lives of Renton, Begbie, Sick Boy and Spud hadn’t abated. Would he like to make it a trilogy?

“Don’t start that rumour,” he laughs. “Of course, if there was a good idea. Coming back was very special, not just with the lads because they’re in such different places in the world now, but coming back here and seeing how much Edinburgh had changed was extraordinary.”

One film he definitely won’t be making is the next instalment in the James Bond franchise, the follow-up to 2015’s Spectre. Boyle and Trainspotting writer John Hodge were appointed last March but left the production a few months later over what have been described as “creative differences”. “We just fell out about the way the script was going,” Boyle has said. American director Cari Joji Fukunaga was eventually appointed and Killing Eve writer Phoebe Waller-Bridge hired to tackle the script. That work is ongoing.

Boyle is still cheerfully sticking his oar in, though, most recently to suggest that Twilight star Robert Pattinson should be the next Bond. But from what he tells me, films on the scale of a Bond production aren’t his thing anyway. Instead his instincts tend more towards what he calls “the co-operative”.

READ MORE: Sir Paul McCartney on his late wife Linda's photography ahead of Glasgow exhibition

“I like to create a group work ethic among people,” he says. “That’s why I’ve always favoured this scale of film. And when I’ve been tempted, as I have been, by the much bigger scale of film which is a different beast altogether, I’ve never really succeeded in it. I much prefer a sense of siege – a group of people who are under siege and trying to make something they love.”

And as John, Paul, George and Ringo famously observed, sometimes love is all you need.

Yesterday is out now

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here