There is nothing remotely loose about a Bridget Riley painting. Every single line and curve has been carefully mapped out by the artist in advance to a microscopic level of detail. I was seven rooms into the National Galleries of Scotland's (NGS) Edinburgh Art Festival summer blockbuster exhibition of work by the queen of Op Art when this particular penny dropped into place in front of my over-stimulated eyes.

It was in Room 7 of the Royal Scottish Academy's (RSA) handsome neo-classical interior that I found Riley's modus operandi laid bare on 72 separate studies on note paper and graph paper. The London-born artist, still creating at the age of 88, has worked with studio assistants since the early 1960s. In clean, slightly sloping handwriting, with the dot on her i's veering towards a line, like an acute accent, she sets out visual and written instructions for them for each painting.

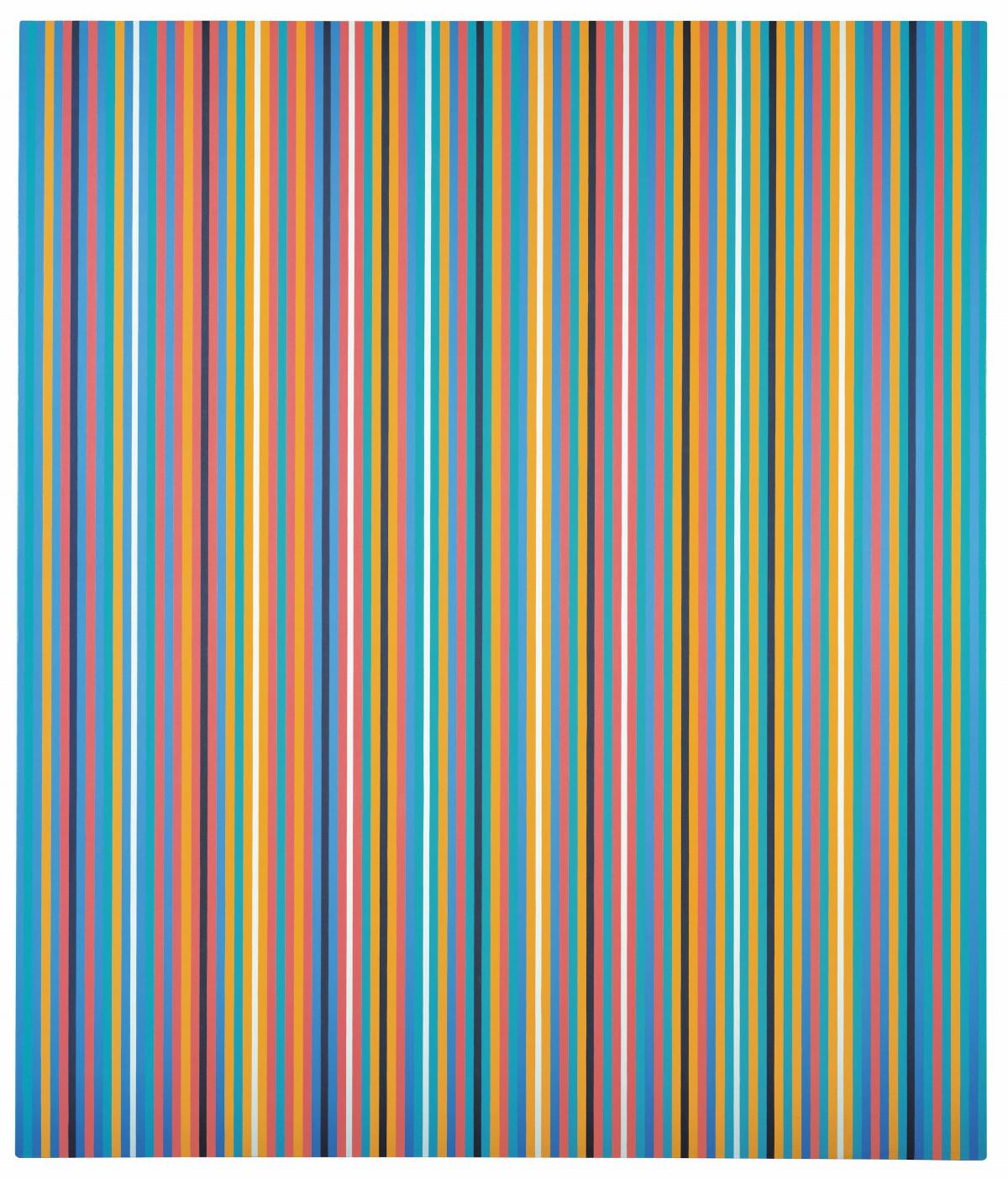

In one section, on seven separate sheets, in words and pictures, she gives an analysis of Rise 1, a painting she made in 1985 made up of horizontal stripes in orange, violet, racing green and white. In one section, Riley notes: "The three possible juxtapositions; equal presentations. The orange being so much stronger acts as a sort of indicative – a leader of the other colours."

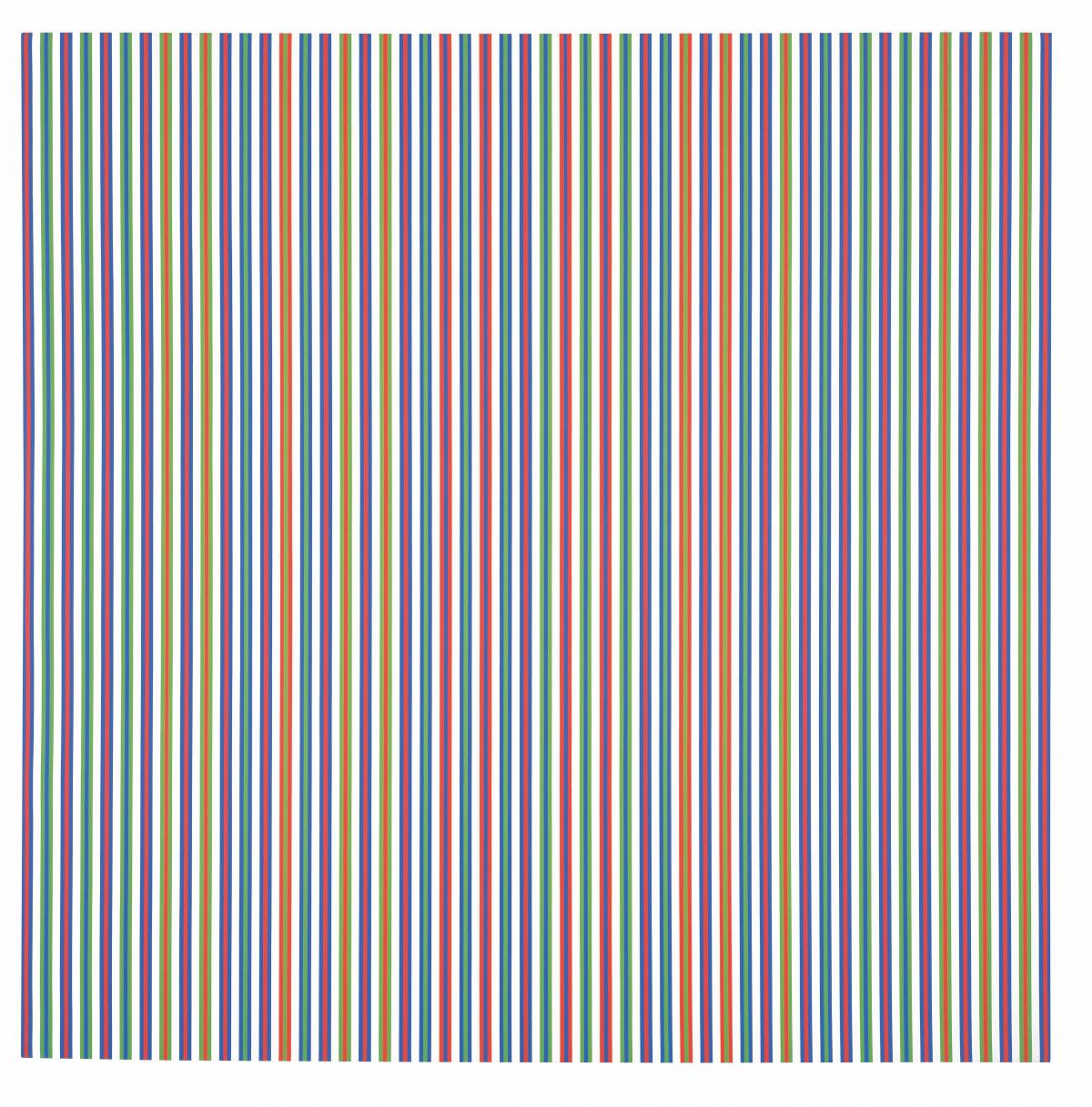

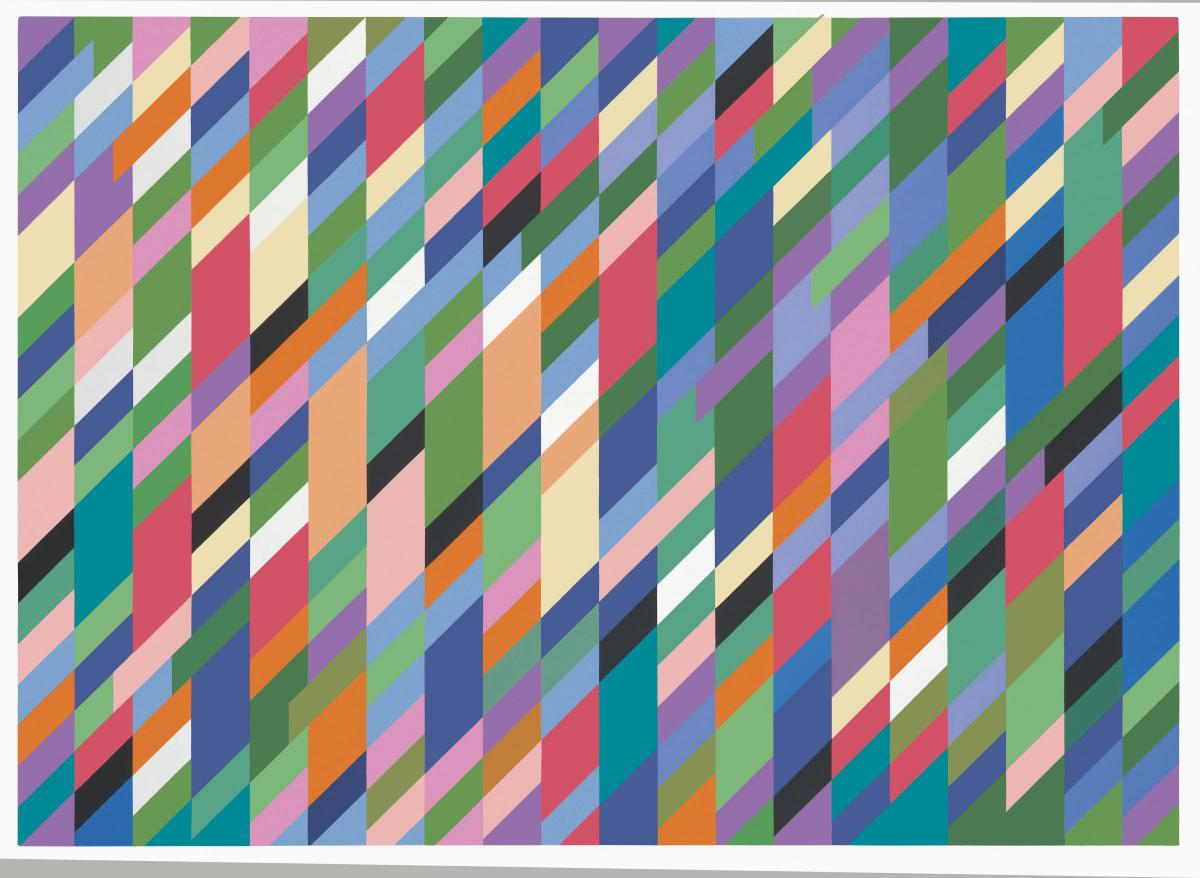

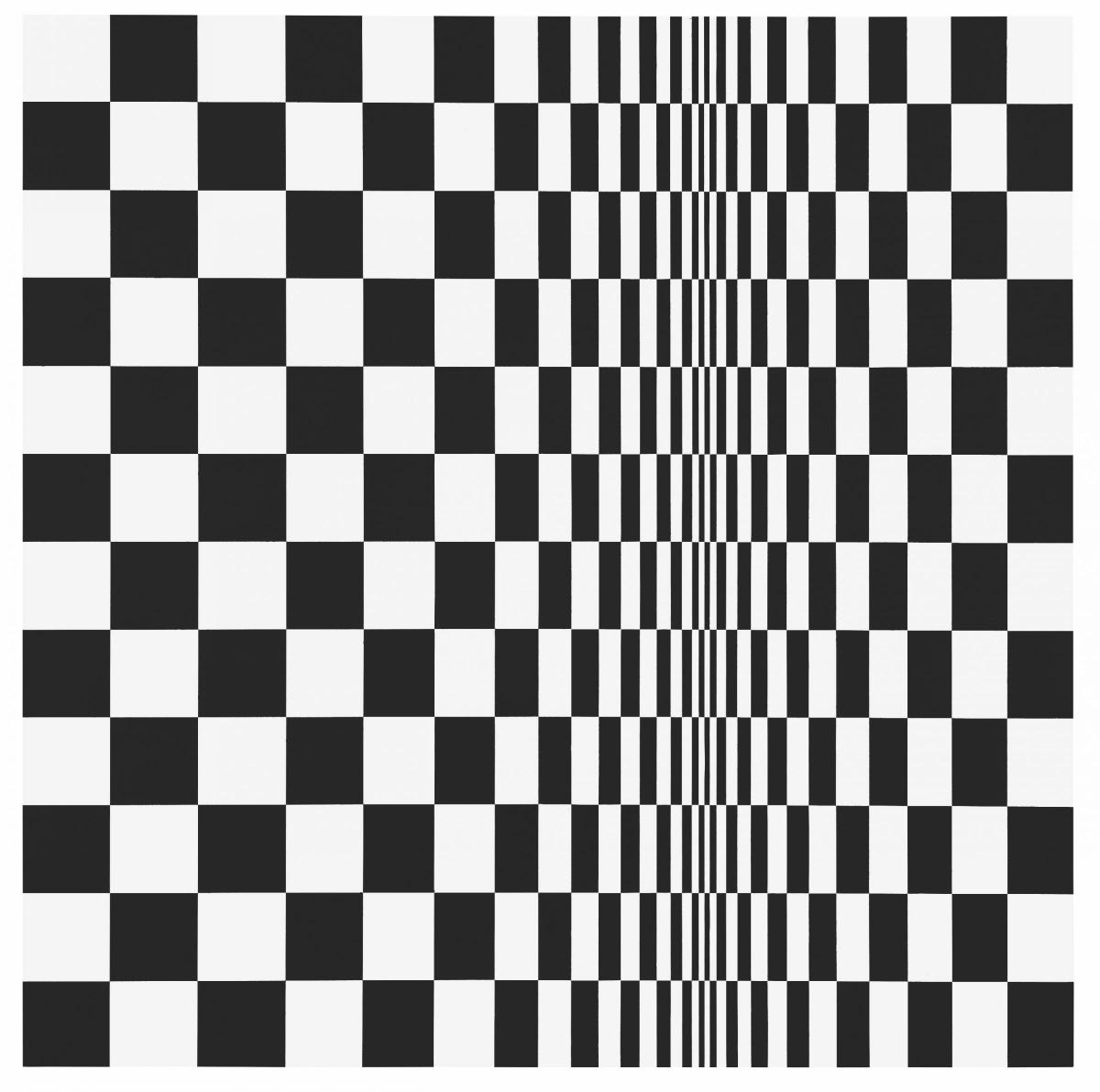

Famous for creating optical illusions within the strict boundaries of a flat surface, Riley's earliest abstract works were closely associated with the emergence of Op Art, one of the last modern movements in art, which first emerged into the public realm in the early 1960s.

Her work was the visual backdrop for the 1960s as they swung into action from London's Carnaby Street and beyond. In 1964, writing about Riley's work in the Whitechapel Gallery in London, art critic David Thompson described her paintings as having the ability to "induce a startlingly effective kinesthetic response". But, he added, as if to silence critics who dismissed her work being tricksy, the key to her art was the fact "geometric abstraction works as a direct expression of feeling."

More than half a century later these words still ring true in this first major survey of Riley’s work to be held in the UK for 16 years and the first of its scale to be staged in Scotland.

Organised by the NGS in close collaboration with Riley, and presented in partnership with London's Hayward Gallery, the exhibition is at the RSA in the centre of Edinburgh until September, before heading to the Hayward, where it will be shown from October until January next year.

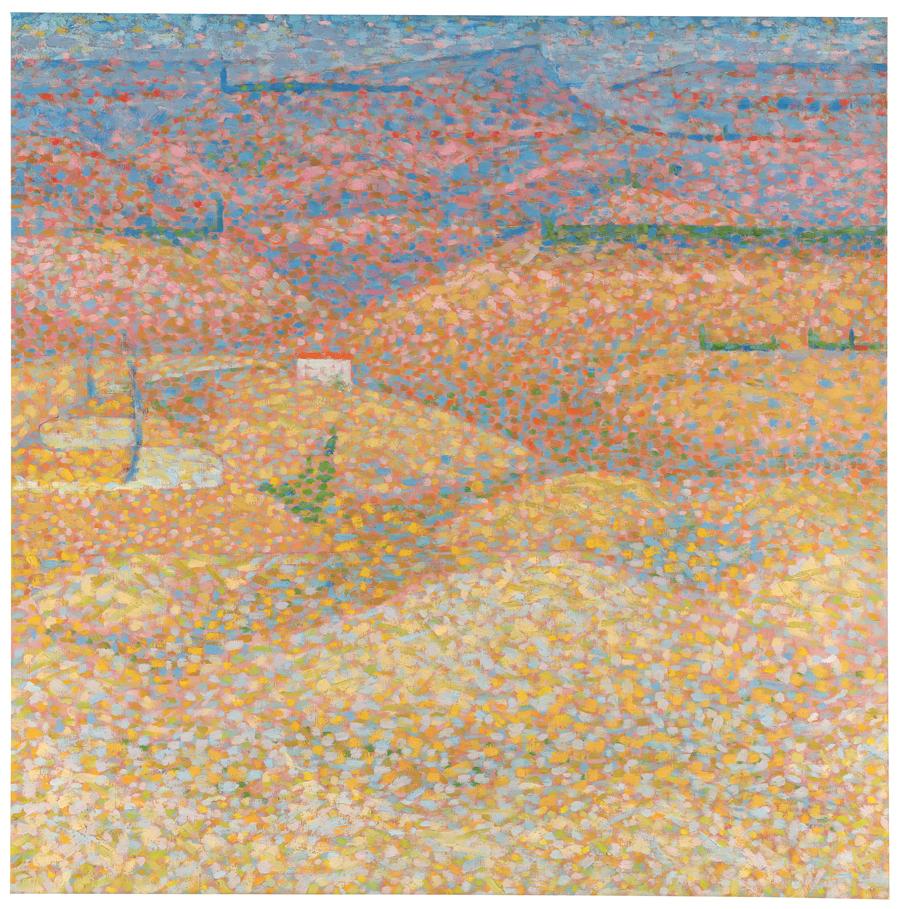

A beezer of an exhibition, which has been years in the making, over ten rooms in the RSA's upper and lower galleries, the artistic life of Riley is laid out for all to see, from lines of development, through seminal works and – in the last rooms – her very early drawings and painting. The voyage around this grande dame of contemporary art starts with influence of French Post-Impressionist artist, Georges Seurat, in Room 1. The panels in every room shed more and more light on Riley as the viewer moves through the exhibition, but this first room sets the scene.

Riley's own words open the exhibition. "What I learned from Seurat," she says, "comes up in different guises, again and again, and one could talk about every later painting of mine in terms of those insights."

In this one room, where work ranges from the late 1950s to 2012, we quickly discover that in an attempt to understand colour and light after a rigorous academic training in fine art at Goldsmith's College in London from 1949-1952, Riley began to pick apart and copy Seurat's painting The Bridge at Courbevoie. This copy, made in 1959, is one of the first works visitors encounter in the show. According to the artist, Seurat's work gave her a sense of the viewer's importance as an "active participant" in which "perception became the medium."

Riley's own abstract visual language started to take shape from this point and as viewers, we are immediately rocked back on our heels with major early works such as Cataract 3, painted on board using synthetic emulsion and PVA in 1967. A word of warning; if you are feeling lightheaded before you enter this exhibition, you might want to go and settle your eyes in a darkened room at this point. You will only get more and more dizzy…

As you move from room to room, the major themes in Riley's paintings are clear as day. From black-and-white, to curves, to exploring sensation, stripes and diagonals, wall painting, studies and recent work, we trace the continuing influence of painters such as Monet, Cézanne, Matisse, Mondrian and Klee. For Riley, making art is all about the way in which we learn through looking, using a purely abstract language of simple shapes, forms and colour to create sensations of light, space, volume, rhythm and movement.

Always ahead of the curve, there is even a very Riley-esque take on graffiti art. Her first wall-based art was created in 1985 at the age of 53; a commission for the Royal Liverpool University Hospital. This was followed in 1997 with a large-scale wall drawing, made for a group exhibition, White Noise, at Bern Kunsthalle in Switzerland. For this exhibition, her assistants travelled to Edinburgh to painted a vivid large-scale work called Rajasthan, 2012, onto the pristine plaster wall of the RSA building. They will remove it when the exhibition ends.

If there really is such a thing as a sight for sore eyes, I encountered it in the darkened rooms of the lower galleries. After the full Riley in the upper galleries, there is an altogether calmer experience in the final three rooms of the exhibition. The artist has recently returned to the subject matter which fascinated her in her early days; namely dots as well as black-and-white shapes.

By returning to the dot, or a disc as she puts it, Riley has been pulled back to Seurat. Her most recent series of paintings and studies entitled, Measure for Measure, one of which was completed earlier this year, reveal her ongoing engagement with Seurat's work and his use of gentle colour to generate light. In works such as Cascando, Riley's recent reverting back to black-and-white also shows a new approach to the scale and organisation of shapes, bringing about a slower pace in the business of looking.

Any exhibition which ends with Beginnings is a sure-fire winner in my book. The final room takes us right back to where it all began for Riley. Pre-abstraction, early works going back to her school days at Cheltenham Ladies College in the 1940s and later Goldsmiths, followed by a spell at the Royal College of Art in London, reveal a precocious talent. Boy, could Riley draw, as illustrated by almost every scrap of paper and full-formed canvas on show in this section. Her copy of Van Eyck's Man in a Red Turban, which apparently gained her entrance to Goldsmiths, is a show-stopper.

In this section, there is a series of detailed notes, including line drawings, a tonal study and a colour analysis, which Riley made in the summer of 1959, when travelling through Italy. She made the observations outside Siena, when driving around and with a thunderstorm looming. Back in her London studio, the notes led to Pink Landscape, which she painted the following year and which now hangs in the first room of the exhibition.

It's beautiful touch and an apt book-end to a bobby dazzler of an exhibition which burns its way into your retinas and feeds your soul.

Bridget Riley, Royal Scottish Academy, The Mound, Edinburgh EH2 2EL, 0131 624 6200, nationalgalleries.org. Until September 22. Tickets: £15-£13 (Concessions available), 25 & under: £10-£8.50. Free for Friends of NGoS

Critic's Choice

Successful artists immerse themselves in their art. It's the only way. Helen Glassford happens to be a successful artist while also balancing a parallel career as founding director and curator of the Tatha Gallery in Newport-on-Tay. In its four years in existence, the Tatha (Gaelic for Tay) has been making waves in the art world by presenting a host of high quality exhibitions. Artists they have shown during this time include; Norman Gilbert, Marian Leven and Will Maclean, Frances Walker, Kate Downie, Ronnie Forbes and Richard Demarco, Calum McClure and Ruth Nicol to name but a few.

Together with co-director, Lindsay Bennett, Glassford has displayed a mix of steadfast integrity coupled with quiet determination to introduce the work of existing and emerging talent to new audiences.

In the last year, Glassford has juggled her day job with creating a new body of work, travelling in all seasons and in all weathers to some of the most secluded parts of the Scottish landscape and immersing herself in the changing weather patterns.

There are 45 oil paintings in Immerse; all inspired by the fascination Glassford has with laying down in paint a feeling for the many unpredictable and feral moods of the Scottish landscape. Planting herself on deserted beaches or rocky outcrops, sketchbook in hand, she quickly makes marks in situ, recording and noting the feel of the weather and the sense of the place.

Human insignificance in the face of nature is writ large in these works, which blur sea, sky and land to the point of abstraction. It's nature, but not as any camera could record it. These paintings, with names like Permeable Land, Revealed and Roam, suggest a fleetness of expression, with drips of rain on scumbled steel-grey skies broken up by horizontal rain.

As art historian Tom Normand writes in the catalogue which accompanies this exhibition, Glassford is "recognising the landscape as pristine experience" and in the process of creating Immerse, has created a body of work which is "endlessly mysterious."

Helen Glassford – Immerse, Tatha Gallery, 1 High Street, Newport-on-Tay, Fife, DD6 8AB, 01382 690800. Until August 24. Open every day but Tuesday & Sunday from 10.30am-5pm

Don't Miss

There's a real buzz surrounding the big Linda McCartney photographic exhibition, which opens at Glasgow's Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery today. I predict this show, which runs until January 12 next year, is going to be a massive draw. Curated by the late Linda McCartney's family; husband Paul and daughters, Mary and Stella, it includes photographs of some of the biggest names in the music industry from the 1960s as well as more intimate family pictures, many shot at the McCartney family's farm in Kintyre. The exhibition also features ephemera and archive material, on show in public for the first time. This includes one of Linda’s diaries from the 1960s, her cameras and photographic equipment.

The Linda McCartney Retrospective, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Argyle Street, Glasgow G3 8AG, 0141 276 9599, https://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/event/1/linda-mccartney-retrospective. Until Jan 12, 2020. Mon-Thur & Sat, 10am-5pm; Fri & Sun,11am-5pm. £7/£5

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here