"MY parents would be appalled by this book," Kate Charlesworth admits as we sit drinking tea and eating Tunnocks Caramel Wafers in the front room of her house just off Leith Walk. "It would have shamed them and I feel very bad about that. They were of their age but the only thing they didn't like about my behaviour was my sexuality."

Love and disappointment. This is Kate Charlesworth's story. Yours and mine, too, more than likely.

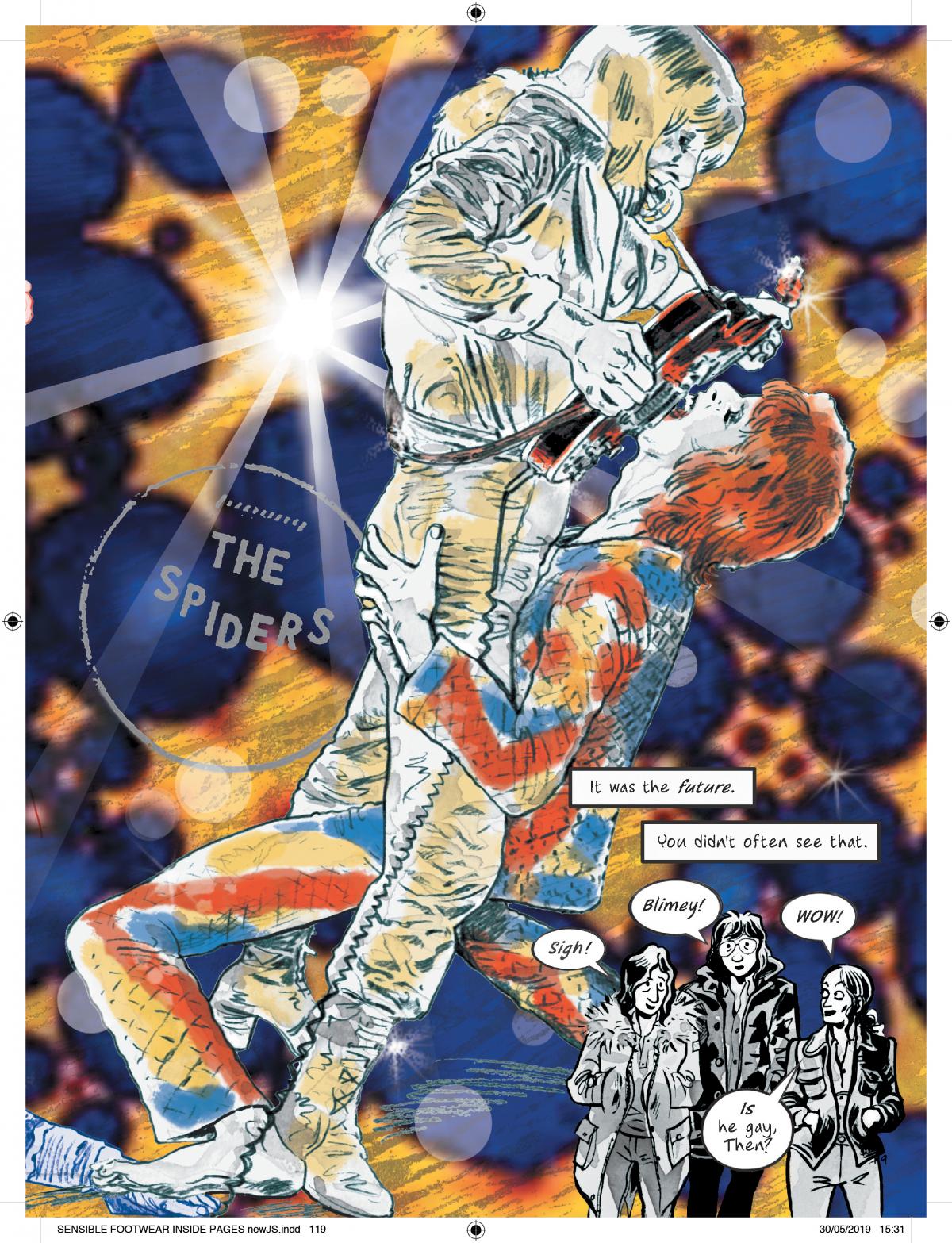

Charlesworth, 69, is one of the nation's finest cartoonists. Over the years she has created comic strips for everyone from City Limits to Gay News, the Pink Paper to the Guardian and New Scientist. She has also spent the last four years working on her latest book, Sensible Footwear. And that’s not to mention the couple of decades thinking about it.

And now it is here, with all the baggage that any and all books carry. All that hope and fear and love.

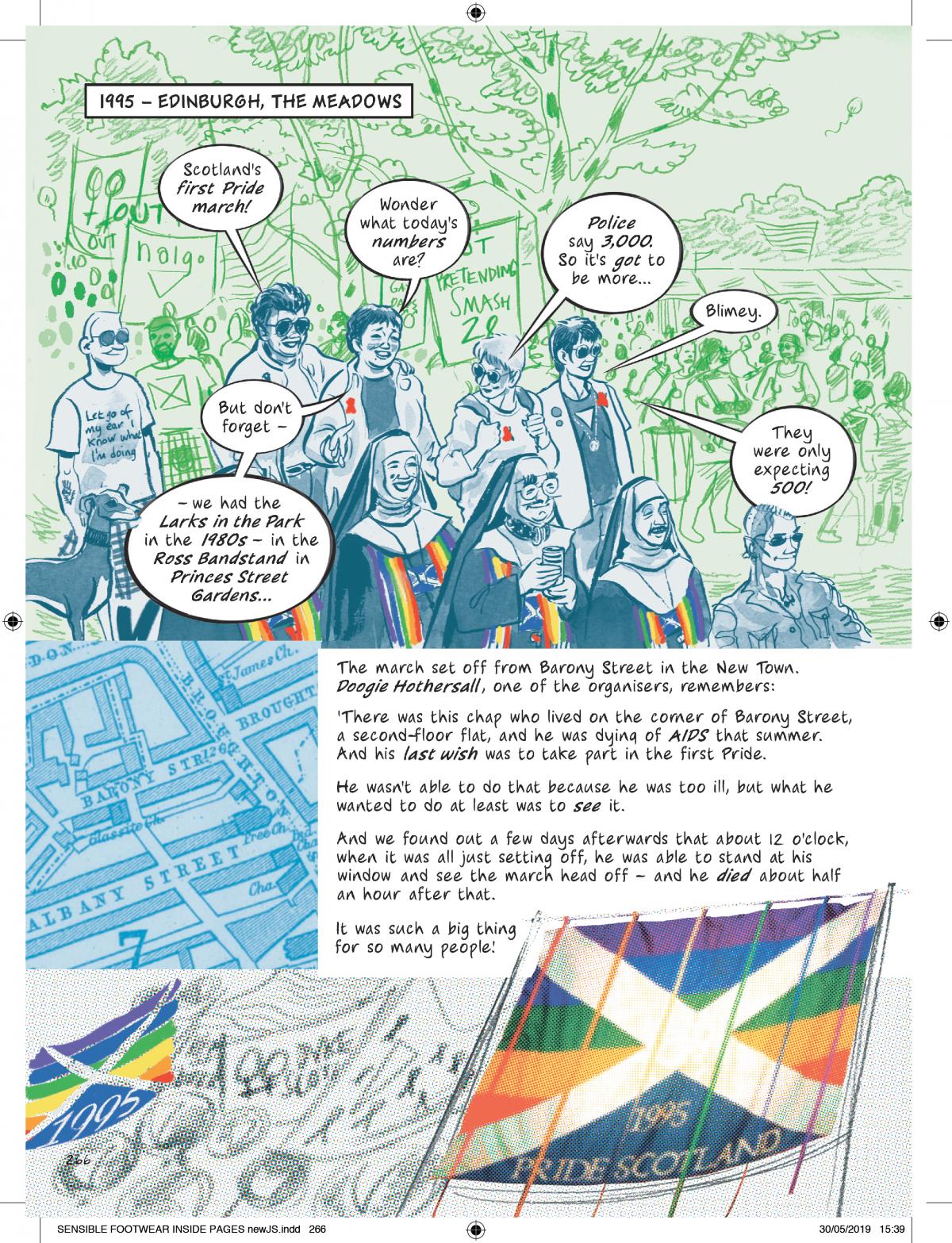

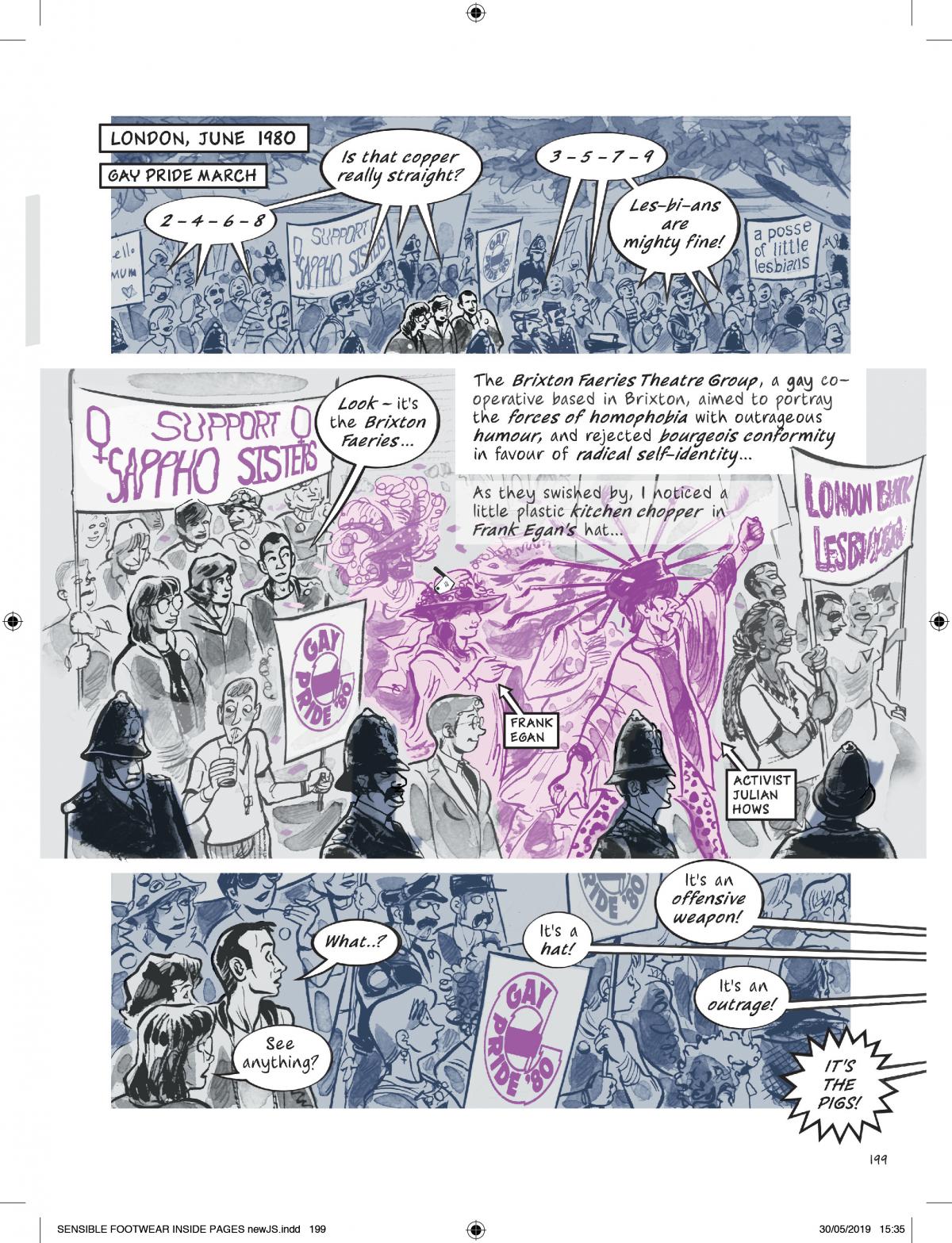

Sensible Footwear tells her own story. But it is also the story of gay and lesbian life in the UK since 1950 (the year of Charlesworth's birth). It follows an arc from homosexuality as a criminal act (for gay men, at least) to civil partnerships, from shame to pride (and Pride), from the chemical castration of the scientist Alan Turing to a moment when he is now set to appear on legal tender, via Sir John Gielgud (arrested for cottaging in 1953 and feared his career was over), Joe Orton, Dusty Springfield, Mary Whitehouse, Brookside's lesbian kiss, gay pride marches, the lesbian sex wars of the 1980s, the Aids virus, Section 28 and Ruth Davidson.

All of it filtered through Charlesworth's personal story of moving from Yorkshire to London and then to Scotland, of coming out and finding her place in the world and navigating politics, passion and, yes, parental disapproval.

It's a wonderfully colourful and candid book, full of Charlesworth's crisp, clean, simple lines and her nuanced vision of human complexity.

Along the way, it takes in Charlesworth's love of Gilbert & Sullivan and reminds us of semi-forgotten lesbian lives such as Nancy Spain, whose "butch" look and sexuality was repackaged as eccentricity for British TV in the 1950s, the journalist Jackie Forster, who came out in Hyde Park at Speakers' Corner in 1969 and co-founded Sappho magazine (where she published some of Charlesworth's early cartoons) and Labour MP Maureen Colquhoun, the first openly lesbian MP elected to the House of Commons in 1974 and treated badly by everyone in it, including members of her own party.

"I was going to illustrate her life story at one time. I remember going around to her house in Hackney. She was an eccentric. I think Maureen's still alive and giving it to them in the Lake District. She was outrageously forthright and an extremely strong character – she probably would have had to be to have the guts to do that."

Read More: Jessica Martin on life and light entertainment

Charlesworth herself grew up in 1960s Yorkshire where her parents ran a corner shop. "I was never particularly interested in sexuality," she says of her childhood and teenage years. "I never had the stirrings. I'd heard about lesbianism and one night a penny dropped, you know? 'Oh my God, I wouldn't surprised if I turned out to be one of them.' I had a dark night of the soul for about 24 hours. And then I thought: 'Do I fancy anybody? No. Not blokes or women or anything.' And quite pragmatically I thought I'd leave it until I do. Which was quite a while, it turned out."

It wasn't until she went to Manchester to study art in the early 1970s that she began to explore "the misty unmapped world of feminine homosexuality," as her hidden copy of lesbian magazine Arena Three had it.

"When I first came out there were these rules about what you could do and what you couldn't do. You had to be butch or femme and you were looked at with great suspicion if you didn't seem to be declaring for one or the other."

That extended to what you wore. "When I was a baby dyke a lot of the butch dykes styled themselves on Rod Stewart. I don't know if he ever knew that. For younger butches, fashion was changing. They started throwing off the gents' natty suits and they were wearing loons and scarves around their necks. And mullets. Some of them looked a bit like the band Mud, which is not perhaps so great. But the raffish ones favoured Rodney."

That lesbian self-policing of look and behaviour didn't end there. "It happened again in the eighties in the lesbian sex wars. It's almost too ghastly to go into. What sort of lesbian are you going to be? There was a slogan: 'lesbianism is feminism in practice' or words to that effect. And quite a few women were political lesbians who had declared themselves lesbians because that was the logical conclusion. You don't sleep with the enemy."

Of course, in the 1970s and 1980s when the battle for gay rights was such a livewire issue it would have been almost impossible not to find the political in the very personal.

"Being a dyke has never been illegal,” Charlesworth points out. “So, I never had that struggle. I was never under the threat of imprisonment or fining or shaming or blackmail. What guys had to go through is a completely different scenario."

Even so, Charlesworth was willing to march and stand up for gay rights in the face of abuse and oppression and "that vile" Thatcher government which introduced Section 28, which banned the “promotion” of homosexuality.

"That legislation was intended to send us all back under the stones from which we'd apparently crawled,” Charlesworth says. “But it had the opposite effect. These quite disparate communities were knitted together. Leather men and dykes walking along together, shouting: 'Stop Section 28.'"

Charlesworth’s life inevitably filtered into her work. She was an illustrator by day, but she also started creating cartoons for lesbian magazines and Gay News. "I was gradually being politicised as a feminist, but also a lesbian. But I was never a separatist. I had extremely good gay male friends and I didn't want to go to that extreme. I never have."

She wonders, though, if that affected her creativity. "I always think that I would have been a better, fiercer cartoonist if I'd been straight because I've not had to live with men. I've never had to go through that whole man/woman thing. Heteronormativity, as I've been trained to say."

Her parents were always encouraging about her work. Her personal life was a different story. Her mother struggled with it, particularly.

Her father, she says, was a little more understanding. "He was a sweetheart. He had been around the world in the war and he had seen a bit more of life and mum just hadn't. And because my mum was unhappy, my dad was unhappy. I think he probably wouldn't have bothered me too much, but he had to live with her."

Was it a subject that they had to draw up a cordon sanitaire around? "Kind of, but it didn't last. It would just erupt occasionally. So, I didn't go back home as much as I might."

It's a source of regret, clearly. And yet she never fell out with her parents. She was never disowned.

"No, they didn't do that. It created conflict and some distress, but that never happened. And later on in mum's life, we came to a kind of accommodation. She was never comfortable with it."

In the end her parents were both creatures of the world they grew up in. Her dad was the youngest of a Victorian family, after all. Charlesworth’s story is the story of gay and lesbian life in the UK; a journey from disapproval (at best), oppression and aggression to acceptance.

And yet, she points out, LGBT hate attacks have gone up of late. She cites the two young women who posted a photograph of their bloodied faces after they were attacked on a London bus in June, outing themselves in the process.

Young lesbians have been lucky to grow up in a post-Section 28 world, she says. "That's great. That's fantastic. But they can't be complacent. I can't be complacent."

The door opens and Charlesworth's partner Dianne comes in. "We've ate all the Tunnocks," Charlesworth confesses. Charlesworth has lived in this house for the last 17 years. She and Dianne have been a couple for 13 of them. They share the house with Sally the dog and Honey the cat.

"I think I've become an accidental Scot," Charlesworth says turning back to me. She moved up from London to the Borders with a former partner.

When that relationship foundered, she contemplated going back to London, but then realised she didn't have to move at all "and a weight literally fell from my shoulders. It felt extraordinary. I didn't realise how much I was carrying around. And I thought: 'Sod it, I'll stay.'

"And I've lived longer in this house than anywhere else in my life."

Now that Sensible Footwear is finished, she and Dianne are working how to live without this monster of a book dominating their lives.

"It's been really strange," Dianne admits. "because for the last two years I've been used to organising things with friends and going out and doing things and then when Kate had stopped doing the book, I'd completely forgotten to include her. Kate was going, 'Can I come?' 'Sorry, I haven't got you a ticket.'"

What is this? What else but a love story? Kate Charlesworth is a cartoonist, a partner and a daughter to now sadly deceased parents. She has written and published a book that she should be proud of. There's no shame in any of this. No shame at all.

Sensible Footwear, by Kate Charlesworth, is published by Myriad Editions, £17.99. She is appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on August 19.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here