Cut and Paste, a phenomenally wide-ranging exhibition covering 400 years of items which can conceivably be called collage, is the first survey of its kind internationally, the National Galleries points out, with its early works dating from the 16th century. Arranged chronologically and thematically, with the intense collage fanaticism of the Victorians, who thought nothing of spending months, perhaps years, in the case of William MacReady and Charles Dickens, who collaged 400 theatrical scenes and portraits on to an extraordinary folding screen, and finishing with the equally infinite variety of Jean-Francois Rauzier's Escher-esque “collaged” photograph of endless rooms in the National Gallery, London. On the way are constructivists, Dadaists, Surrealists, assorted other -ists, and a room full of protest art collages from the 1960s and 1970s, some of which may disturb children – I give fair warning - including some seminal film by the late Carolee Schneemann, in which she herself becomes the “collage”.

Perhaps what strikes one first is the diversity of the artform which most people first encounter at school when handed a magazine, a pair of scissors and a glue stick. But if this essential sticking of things onto other things is understood to be “collage”, the definition of the form and its parameters have long been squabbled over. Given its formative period in the innovative art movements of the early twentieth century, this is perhaps no surprise. Collage was – and indeed remains in many ways - a medium in which artists could express their divergence from the traditional media of painting and drawing by quite literally mixing things up a bit. Collage was the breaking up of the image; the making of something new.

Picasso and Braques were instrumental in taking up the medium, although each generation of artistic movements reinvented it for themselves. Hand-in-hand with collage goes trompe l'oeuil, a gift both to the Victorians and the absurdists, the former treating collage as applique, a careful layering of neatly placed elements to form a picture rather like a puzzle being put together – either as realism or surrealism, depending on the humour of the compiler; the latter, exploding these elements to create scenarios in which fish float amongst women, or men acquire birds heads, almost seamlessly, in the case of Max Ernst, inserted over an original print. Normality oddly subverted; a hark back to the Victorians, the absurd an organic part of the every day.

There are things here too, which defy the notion of collage, at first glance. Tirzah Garwood's lovely, unassuming box collage of The Chapel, Halstead, 1947, is a construction of paper and cardboard, a miniature model frontage of the chapel near to where Garwood and her fellow artist husband, Eric Ravilious, lived. There is a collection of beautifully-arranged screws from a shop display case, c. 1937. There is a shopfront “collage” of a collection of toys - “The Toy Shop” 1962 - by Peter Blake.

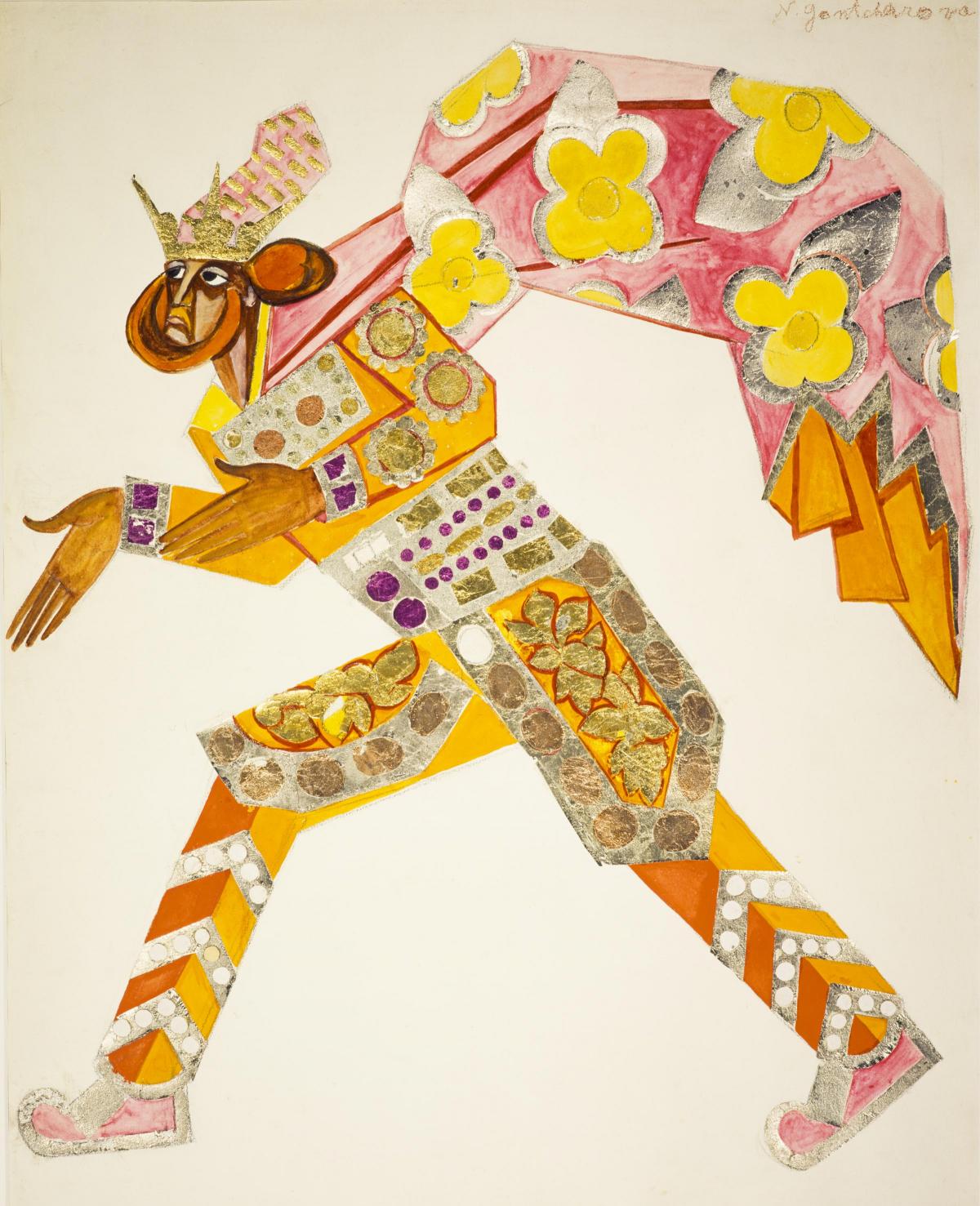

There is Picasso's “Head” 1913, which places strips of paper and paint in an assemblage. Picasso in turn inspired the likes of John Piper, who, between 1936 and 1939, as the accompanying exhibition catalogue notes, spent three years travelling around England creating collage landscapes such as “Archaeological Wiltshire”, tearing strips of paper as substrates of land and form, painting, inking over them. There are the robotic constructions of Andre Breton, Jacqueline Lamba and Yves Tanguy's “Cadavre Exquis” 1938. There are the striking, stylized costume designs of Natalia Goncharova (1915), created for Diaghilev's Ballet Russes and Peter Kennard's politically-manipulated “Haywain with Cruise Missiles” (1980). And then, the magical “paper transformation” “Figures and boats on a Lake” c.1800, which prefigures them all, a trompe l'oeuil build up of layered paper which, when held before candlelight would magically change from a daytime to a moonlit scene.

The lot ranges from intricate trickery to gung-ho bravura. Each says something about its time, about the artists which were attracted to its form. In fact, in the end one might almost think that the only thing holding the whole wild and fascinating assemblage of historical collage together is this notion of disparate parts, wilfully cut or ripped, coming together to form something new. The image behind the image, the image through the image, the layers of life and consciousness transferred into (mostly) two dimensional form.

Edinburgh Art Festival. Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 75 Belford Road, Edinburgh, 0131 624 6200, www.nationalgalleries.org Until 27 Oct, Daily 10am - 5pm, £13/£11/£7.50 (other concessions available)

Don't miss

Strange noises and fragments of over-sized instruments are the order of the day at the Talbot Rice Gallery this month, following their collaboration with Hong Kong-based artist and composer Samson Young, master in the art of improbable noises. Working with academics, he has produced a 50ft-long trumpet, a bugle played with 300 degrees Celsius dragon fire and an indoor garden with 16 speakers sprouting from a landscape littered with gigantic trumpet parts. Whether this stands as an escape from the Festival cacophony outside, or a leap from the frying pan into the fire, time will only tell - but it sounds promising.

Edinburgh Art Festival. Samson Young: Real Music, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, Old College, South Bridge, Edinburgh, 0131 650 2210, www.ed.ac.uk/talbot-rice Until 5 Oct, Mon - Fri, 10am -- 5pm, Sat/Sun 12pm - 5pm

Critic's Choice

Stephen Bird returns to the Scottish Gallery for his fourth solo show, part of the Edinburgh Art Festival along with the other exhibitions on display in the city-centre gallery. A native of Dundee, now living in Sydney, Australia, Bird works in bright, bold ceramic, his work a narrative of the gruesome, the grotesque, and other dark notions not generally explored on a dinner plate.

His subjects, if not boldly confronting you in the face, are there in the backdrop, a pastoral scene that at first – and only very first – glance appears cheerfully bucolic, only to reveal blood on the hands, or a bloodied body. In other places, the gore is immediate, brightly rendered, darkly humorous. There are serial “self-portraits”, a layering up of images, inclusions, as if collaged onto the form in a neurotic frenzy of creation. Bird finds his inspiration variously in folklore, in local myth, in English pottery traditions, in the stories of the people – and the art – of his adopted home. Plates are wildly daubed with goggle-eyes, with tartan and biscuits (Nice), penises, frequently all crowded on to the same piece. There is a lot of purposeful walking, too.

Above the terrors hinted at, there is joy in the glaze and the boldness. The creations reference Primitive Art – unschooled, obsessive, “primitive” – but the glazes are brilliantly lustred, the colours singing, if of blood and somewhat menacing broccoli trees.

Edinburgh Art Festival. Stephen Bird: Kiln Gods, The Scottish Gallery, 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, 0131 558 1200 www.scottish-gallery.co.uk Until 24 Aug, Mon – Fri, 10am – 6pm, Sat 10am – 4pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here