IN the archives of The Herald, in the issue dated Monday, August 19, 1996, there is a photograph taken at the Herald Angel awards in Edinburgh’s Festival Theatre two days previously. The winners included the first ever Archangel, presented to actor Miranda Richardson for her performance in an adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and Slava Polunin for the first UK outing of his Snowshow.

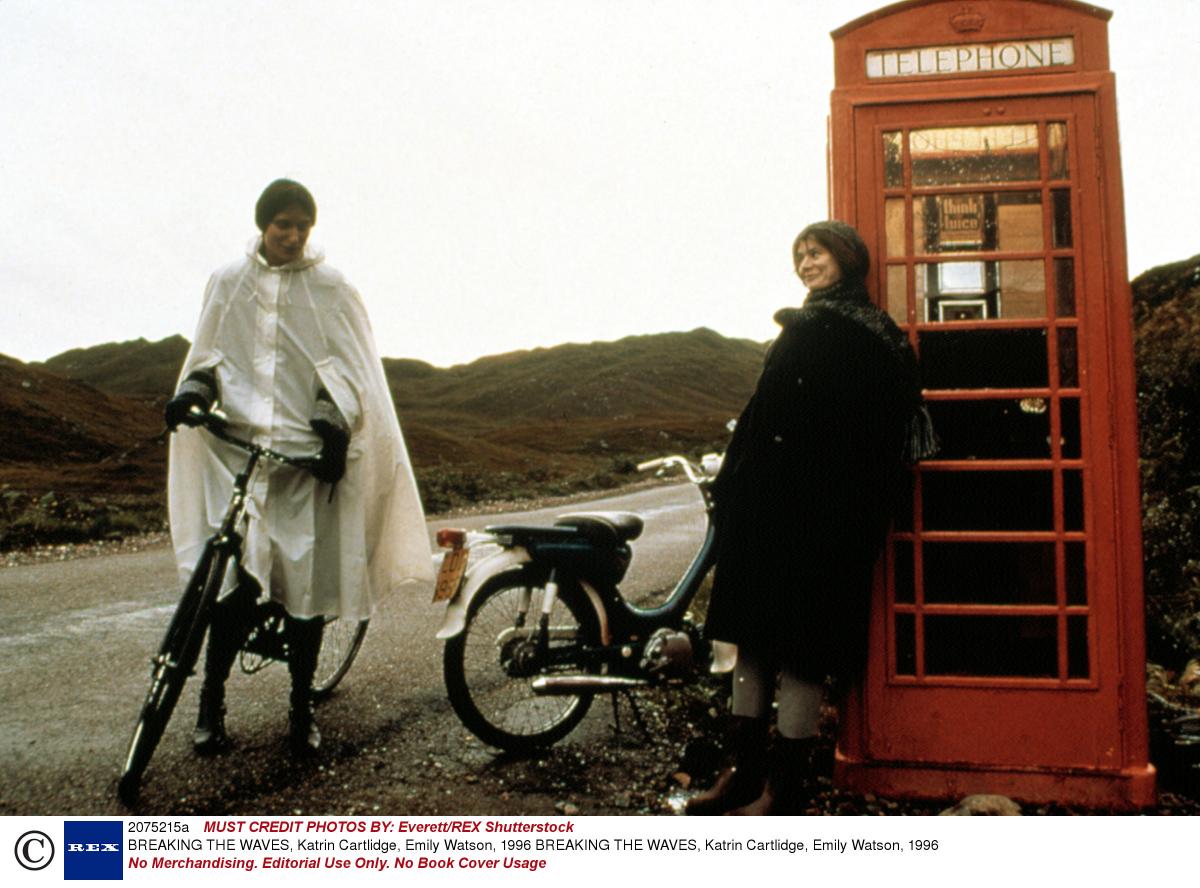

At the bottom left of the group is a young Emily Watson, who had made her startling debut in Lars Von Trier’s film Breaking the Waves, which premiered at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

Twenty-four years later the Edinburgh International Festival hosts the European premiere of American composer Missy Mazzoli’s opera adaptation of the film, in a new production created by Opera Ventures and Scottish Opera, directed by the Bristol Old Vic’s Tom Morris. In the role that won Watson an Angel, her first award, is Californian soprano Sydney Mancasola who made her career in Germany, including Barrie Kosky’s production of the Magic Flute in Berlin, before making her debut at New York’s Metropolitan Opera earlier this year. As rehearsals began in Scottish Opera’s Glasgow studios, the composer and leading lady talked about bringing the controversial Dogme film to the opera stage.

“I didn’t know the movie,” admits Mancasola, “but my parents had seen it. Their generation seem to know it well, so it was obviously a big thing when it came out. I was too young to see it.”

This, of course, is quite true. Watson plays Bess, a young woman in a Scottish Calvinist community who marries Jan, a Norwegian oil worker. When he is disabled in an industrial accident, she complies with his wish that she has risky sexual encounters that he can enjoy vicariously later.

Mazzoli confirms that Von Trier’s story struck a chord with the US audience: “Fifty per cent of the people I mention it to in America know and have seen the film. And that’s true of the audience for the opera as well, but I don’t think you need to have seen it at all. My goal was to write something that made sense to people who had never seen the film.”

Like the soprano, however, Mazzoli was one to those who hadn’t seen it before she embarked on the project.

“It was suggested to me by my librettist, Royce Vavrek, who has loved the film since it came out, which is sort of weird because he was 14! But that aside, the more I thought about it the more the story would’t leave me alone. It has all the hallmarks of great opera.

“You have the purpose of the church, you have this domineering mother, you have this amazing pure love story and this intense drama with big ideas about loyalty and faith, and what it means to be a good person. I think opera is the place for those big ideas.”

A research trip was clearly in order, so Vavrek and Mazzoli booked a flight to see where Von Trier had worked, although it turned out that was not specifically the location of the story.

“Before we wrote a note, we spent five days on the isle of Skye visiting the places where the film was shot, but then quickly realised that was not the point, and it was better to talk to people and immerse ourselves in the physical landscape.”

That, and the music of the country, including later research into psalm-singing in the Presbyterian church for the Western Isles.

“There is a moment of Gaelic song in the piece, or my interpretation of it, I should say.”

Mancasola suggests another influence in the work of Benjamin Britten and particularly Peter Grimes, which many see as the British composer’s most successful opera. It is a comparison the composer quickly concedes.

“It is an opera in English, set in a seaside community about an outcast, and although people are trying to do the right thing, things escalate out of control very quickly. I love Britten and in Peter Grimes the sound of the ocean is always in the music, so I tried to capture a bit of that.”

There are other specific instrumental sounds to listen out for as well.

“The voice of God is the electric guitar. The moment where Jan is on the line between life and death we hear a melodica. The councilmen of the church have a dry staccato woodblock sort of effect,” says Mazzoli.

The portrayal of that oppressive community, as well as the explicit nature of Bess’s sexual encounters, made Breaking the Waves a controversial film, and a difficult watch, when it came out.

A quarter of a century on, it seems reasonable to wonder what has changed.

Mazzoli is adamant that it has not dated at all.

“I feel it is more relevant all the time. I see it as the story of a woman in an impossible situation, where everyone around her is telling her what to do and they are all telling her different things. That has been my experience, and the experience of every woman in my family, and that’s the lens through which I approach the piece.

“It is not about her as a victim, it is about a woman who has a line of acceptable behaviour that is so small that she can’t help but fall off of it. Every woman experiences that, because there all these clashing voices for women; I think even more so now than in 1996.”

Mancasola is just as clear that Bess is not a victim.

“Even though horrific things happen to her, in a weird way a lot of what happens to her is consensual – she walks every step of her path, she makes her decisions.

“I can draw parallels with the sort of remarkable women that people like to write operas about, but in some ways she’s a really different personality. Cleopatra and Musetta [in Puccini’s La boheme] are cerebral and manipulative and I don’t think Bess is a manipulative woman. She is quite the opposite really; she says what she means and people don’t expect that.”

Mazzoli agrees, adding: “Bess has this very clear sense of morality and what it means for her to be a good person, when people around her are resorting to violence and threatening her. She stays true to her own sense of what it means to be loyal, faithful and good. Her objective in the story is very simple: she wants to be with the man she loves. That love is so pure that the community can’t handle it.

“Opera’s superpower is the ability to create subtext through the music, so it is the perfect medium through which to tell this story about someone who has this extraordinary inner life. The music is what illuminates that.”

Bess’s visible life, however, will require Mancasola to perform in a way that shows a woman prepared to embark on dangerous sexual liaisons that she can then tell her husband about. How explicit that will be in the new production had still to be determined when we spoke.

“I am not a squeamish person in general,” she says. “I have been asked to do a lot on stage and nothing has ever fazed me yet, but this is the first time I’ve had some trepidation.

“I find that, as I grow as a person, pieces with heavier, darker subject matter have more of an effect on me personally. Rather than worry about any logistical thing about what I am being asked to do onstage, I am more aware of how this might make me feel as a human, to be playing her onstage.”

Mazzoli says a sensitivity to that was essential as the production was being put together.

“Everyone in the cast was chosen partly to create a good atmosphere in the room, because this is such sensitive material.

“We don’t really know yet how this will all be staged, but it is a story that involves sex so you have to show a sexual relationship between two people.

“But showing intimacy between two people on an operatic stage is different from depicting sex and that is more interesting to me. Exploring those big ideas about loyalty, faith and goodness is the point of the opera; it’s not about the sex and the violence.”

Breaking the Waves opens at the Edinburgh International Festival on Wednesday. It has three performances at the King’s Theatre on August 21, 23 and 24 at 7.15pm. eif.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel