The Last Stone: A Masterclass in Criminal Interrogation

Mark Bowden

Grove Press UK, £16.99

Review by Alasdair McKillop

There were people who didn’t enjoy season three of the American drama True Detective when it was on television at the start of the year. The story was about the disappearance of two children, a brother and sister, from the small town where they lived. People whose judgement I usually trust didn’t bother watching until the end. God it was slow, was it not? Even the performances of Mahershala Ali and Stephen Dorff weren’t enough to hold the interest. It was slow, certainly. But I thought we’d become accustomed to television taking its time with stories. There are episodes of Mad Men in which the only action happens to cigarettes. Sometimes there are things in life that move slowly, for one reason or another. There are certainly circumstances in which that is the case. There are even places where time seems to move slower than it should. Sometimes it seems not to be moving at all. Sometimes it seems to be going backwards.

Imagine how slowly time would move if you were the parent of an abducted child, or a detective trying to work out the why, the who and the where of it. The pacing of True Detective was intended precisely to prove that some answers are not easily obtained, if they are obtained at all. It was a concession to reality, not television.

So much of detective work seems to be about futility, failure of the kind that characterised the investigation into the disappearance of Shelia and Katie Lyon from a shopping mall near Washington DC in March 1975. Mark Bowden was a young reporter at the time working for the Baltimore News-American newspaper. He covered the original investigation and now, more than four decades later, he has written a book about the case.

“A story like this,” he explains, “struck at suburbia’s idea of itself.” Nixon was gone and Vietnam was almost gone; the economic surge of the post-war years and the feel-good vibe of the late 1960s – they were gone too. Despite the moral exhaustion of the time, the disappearance of a child still had the potential to shock, not least in the suburban communities to which people had moved from the city and country in the belief they were leaving behind the world’s unhappiness. The abduction of two obedient girls from a public place was even harder to comprehend. The 1970s investigation produced no answers, meaning, as time went on, no bodies. Shelia and Katie weren’t brought home, but the case never went away completely. It lived in the memory of the police department, not least because one of the girls’ brothers joined some years later. Eventually it was picked up by a cold case team, a group of officers nearing retirement who sifted the evidence from unsolved cases looking for something that might spark them back to life. It was slow work.

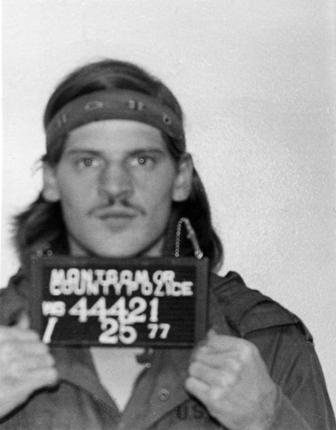

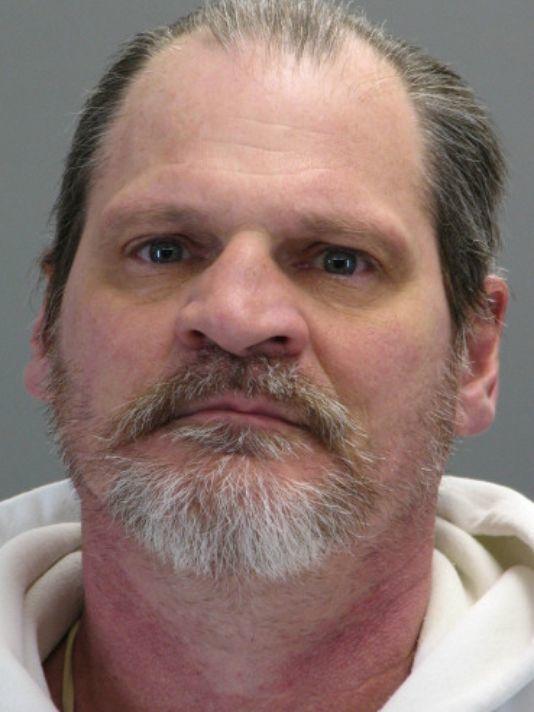

Finally, in 2013, a suspect rose from the paperwork; investigating officers wanted to find someone who might tell them more about his possible activities on the day the Lyon sisters were taken. They turned to Lloyd Welch, a man in prison for molesting the daughter of one of his girlfriends. Back in 1975, Welch had given evidence to the police. He told a story about being at the mall on the day in question, but it was dismissed as a fabrication, which is what it largely was. Now, years later, the police hoped he might be able to give them something useful. A series of long interviews took place over the course of almost two years. A pattern emerged. Lloyd would stick to one version of events until he was worn down enough to reveal a new piece of information. If the officers presented a new and undeniable fact, he would incorporate this into his own account, seemingly unaware that his credibility diminished with each new adjustment. Officers learned that he was good at seizing on potential scenarios and even specific phrases put to him during the interviews. And he started implicating his relatives in the crime.

Lloyd came from a family in which heavy drinking, rape, violence and child abuse were common. He had been physically and sexually abused by his father. They were hill people who moved to urban areas but never settled down. Bowden describes them as being “sealed in the intimacy of their crowded homes, carrying on vicious old habits”, which is on the mild side as far as things go. Time didn’t move forward for the Welches and the old ways remained the only ways they cared to know. Even those few members who managed to live relatively normal lives turned out to have sordid incidents buried deep down in their past like the body of a neighbour’s dead dog in the back garden. The Welch family is what happens when people have no roots in society. I came to think of them as characters from a seedy song by the Drive-By Truckers, like the family in one of the band’s songs who live with “unlocked doors and loaded burglar alarms”.

After reporting on the Lyon’s case, Bowden went to work for the Philadelphia Inquirer. He wrote Black Hawk Down, which was adapted into a successful 2002 film, and books about the Vietnam war and the hunt for the Columbian drug dealer Pablo Escobar. But he still found himself wondering what happened to Sheila and Katie. He was just another person who felt something was incomplete, who wanted to close a truthful circle between now and then. The Last Stone is his attempt to do that. In truth, he is more of a story facilitator than a storyteller. The bulk of the text is drawn from transcripts of interviews with Lloyd and the rest of the Welch family that Bowden has “edited for concision and clarity”. That means the writing, line to line, paragraph to paragraph, is not memorable. Bowden is a largely unobtrusive presence as he allows for the story’s slow unfolding under the pressure of dogged police work. He steps in to highlight discrepancies with previous statements or emphasise the importance of seemingly minor comments, the significance of which might be missed by the reader. Sometimes he’ll hurry interrogations along by summarising exchanges. His role is to clarify and remind and his presence is remarkably minimal. This approach gives the reader a clear sense of the frustration and tedium involved in extracting the truth from someone disparate to keep it hidden. Once again, it was slow work.

The broad outline of the dreadful outcome is very quickly clear enough. What makes the repetitive nature of the long interrogation passages bearable is the need to find out the particulars. Readers and interrogators are at one in this respect, but that isn’t an entirely comfortable position to be in. We’re turning the pages because of the mendacity of the central figure. Eventually there is a result of sorts but not the answers the hard police work merited, and the Lyon family deserved. The book is a tribute to the work, but I’m not sure what it offers the family. It is compelling nonetheless, but how much of the credit should go to Bowden is debatable. I don’t think he would claim much for himself. During one of the last interrogations, the possibility of a book about the case is discussed in the interview room. Officer and suspect didn’t realise they’d almost finished writing it.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here