Richard Purden

Terry O’Neill studied to be a priest before the rector took him aside and said: “Terry, I don’t think you would make a good priest. You have too many questions.” Unperturbed, the East End boy turned his attention to jazz drumming in London clubs from the age of 14.

“I wanted to go to New York, all the jazz guys had to get a job on the boats to get to America. I heard about musicians getting jobs as stewards with BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation) and thought, ‘I can have a three-day layover in New York and then come back to London’. They gave me a job in the photographic unit and suddenly I’m a photographer.”

O’Neill, now 81, had an eventful childhood. He was born in London to Irish parents and knew families that were killed during the Second World War by Nazi buzz bombs.

He recalls his early breaks. “It was the early 1960s and the advent of pop. I was sent to take a picture of The Beatles who were recording at Abbey Road. I then had a call from Andrew Loog Oldham, The Rolling Stones manager, who asked me if I could do for them what I did for The Beatles.” He suggests both experiences were in sharp contrast. “The Beatles all spoke at the same time, they were four guys wrapped up in one. The Stones were five individuals but Brian Jones was the leader and he got paid more, he was a great blues player but he could be difficult, especially when drugs came in.”

O’Neill went on to become one of the main photographers at the centre of Swinging London. “Those were my first two jobs and I never looked back.” It wasn’t long before movie studios hired O’ Neill for legendary shoots with the likes of Brigitte Bardot, Elizabeth Taylor and Ava Gardner. The latter wrote him a letter of recommendation to Frank Sinatra. “When I told her I was going to be taking pictures of her ex she said: ‘I’ll write you a letter. When I gave it to Frank he said to everyone around him: ‘Right, this guy’s with me’ and I sort of was for the next 30 years. He gave me all sorts of access and never questioned anything, it was incredible.”

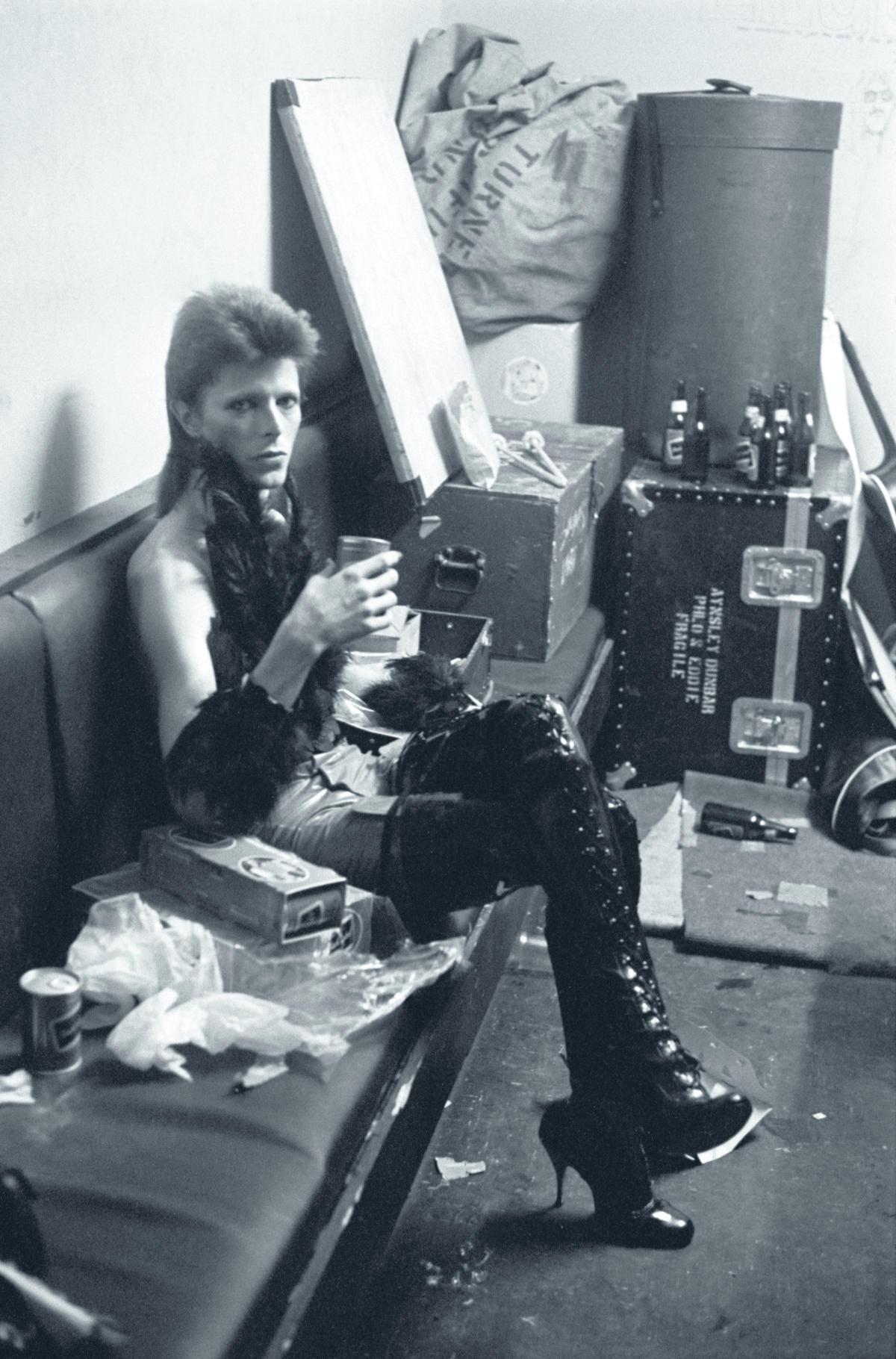

His most creative partnership began just as David Bowie killed off his much-loved alter ego Ziggy Stardust at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in July 1973. Ziggy was granted a final swansong when Bowie snuffed the character out by letting him erupt for one final performance. It was his most outrageous expression yet. “I went to the Marquee Club in Soho”, says O’Neill. “David’s manager called and said he needed publicity shots of David doing this last performance as Ziggy for American television. I went down and shot everything I saw.”

Freddie Buretti’s Angel of Death red vinyl costume with black feathers from The 1980 Floor Show performance still had the power to startle 40 years later at the Bowie’s V&A exhibition in London. “He shocked people when he came on stage, that was when he looked his most androgynous ”, says O’Neill.

“The place was rocking, he had about 200 fan club members in, it was packed. From that session, I liked the backstage shots where he is getting his make-up done and smoking a cigarette. His former wife Angie was always beside him at that point, they were a very striking celebrity couple.”

O’Neill was now the snapper on hand to capture Bowie’s imperial phase morphing from Ziggy into Halloween Jack through to The Gouster and The Thin White Duke. A month later he was invited to Bowie’s London home to document a meeting with William Burroughs for Rolling Stone magazine. “David was a great poser but Burroughs was even better, he took over the session. There was a great chemistry and a lot of mutual admiration.”

Inspired by Nova Express Bowie would adopt the cut-up method Burroughs deployed for the novel when writing his next album Diamond Dogs. Once again it was O’Neill called in to help develop the album’s artwork. Bowie had become alien-like for the cover of his previous long-player Aladdin Sane but the sleeve for Diamond Dogs would remain his most uncanny. Appearing as half-man and half-dog alongside two creatures based on “freak show” performers, O’Neill’s images were used by artist Guy Peellaert to create the arresting image. “I got to do all the pictures for the album cover, a dog was brought in and David copied what the dog was doing which I photographed and Guy turned it into that fantastic cover. “I also did a shot with David and another dog jumping up at the strobe light going off. Bowie didn’t turn a hair; I’m not sure what he was on at the time but he was so cool. He was the coolest guy you could ever meet.”

The assignments continued when Bowie relocated to America and began to absorb black experience, language, fashion and culture, before recording Young Americans. The cocaine he had dabbled with was now becoming an addiction. O’Neill remembers an exhausted Bowie styling himself before another memorable shoot. “David appeared with this mustard yellow suit, his haircut was now yellow and orange. He would pick up a pair of scissors or smoke a cigarette and make it mean something. He was just brilliant and in that way, he wasn’t like a pop star at all. I used to shoot him as if he was an actor playing all these different roles.”

O’ Neill’s comments chime with the American chat show host Dick Cavett who told Bowie around the same time that he seemed like “a working actor”. O’Neill suggests it didn’t come as a surprise when Bowie was invited to play the lead in The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) under the direction of his friend Nicolas Roeg. The photographer was involved with a previous invitation from Elizabeth Taylor who wanted Bowie to appear in The Blue Bird (1976). After arriving four hours late, tardiness probably cost him the role but it also helped Bowie dodge a bullet as the film was a commercial and critical flop.

O’Neill didn’t waste the opportunity. “The light goes in LA about 6 o’clock so I had about five minutes to work with and grab those pictures of David and Liz. I just worked away and used about three rolls of film. There was a good energy and Liz just lead the whole thing – she was such a pro. I don’t think David knew what hit him, he was like a lost boy at one point, maybe she knew he was on drugs because she was more hip to all that than me.”

Bowie takes on a healthier-looking form in shots taken later that year at the 50th birthday party of Peter Sellers, in the role of Thomas Jerome Newton in The Man Who Fell To Earth and as The Thin White Duke in 1976 touring Station To Station.

O’Neill would photograph Bowie only once more in 1992. “He just called me up himself on that occasion, there was no manager to deal with. We did the shoot in London for the cover of Premiere, the film magazine and some other projects he was working on. The secret to working with David was shooting him in different roles but he was just being himself, there was no character to hide behind. I think in those pictures you can see what a great looking guy he was, that was the last time. I didn’t see a lot of him after that, we talked now and again. When he died it came as a total shock, the nation was shocked – it felt even bigger than when John Lennon was shot.”

Reflecting on the clutch of various images he adds: “I took pictures of The Beatles, The Stones, Elton and Clapton but there was no one like him. Apart from being such a creative man he was a good guy and one of the most charming and nicest people I ever met in my life.” Is there anyone current O’Neill would consider coming out of retirement for? “I don’t want to take pictures anymore, there’s no access and there’s no one I want to photograph. The Voice and X-Factor have ruined what singing is really about, it’s a joke. The creative talent is simply not there. I’ve done my bit and I had a great time.”

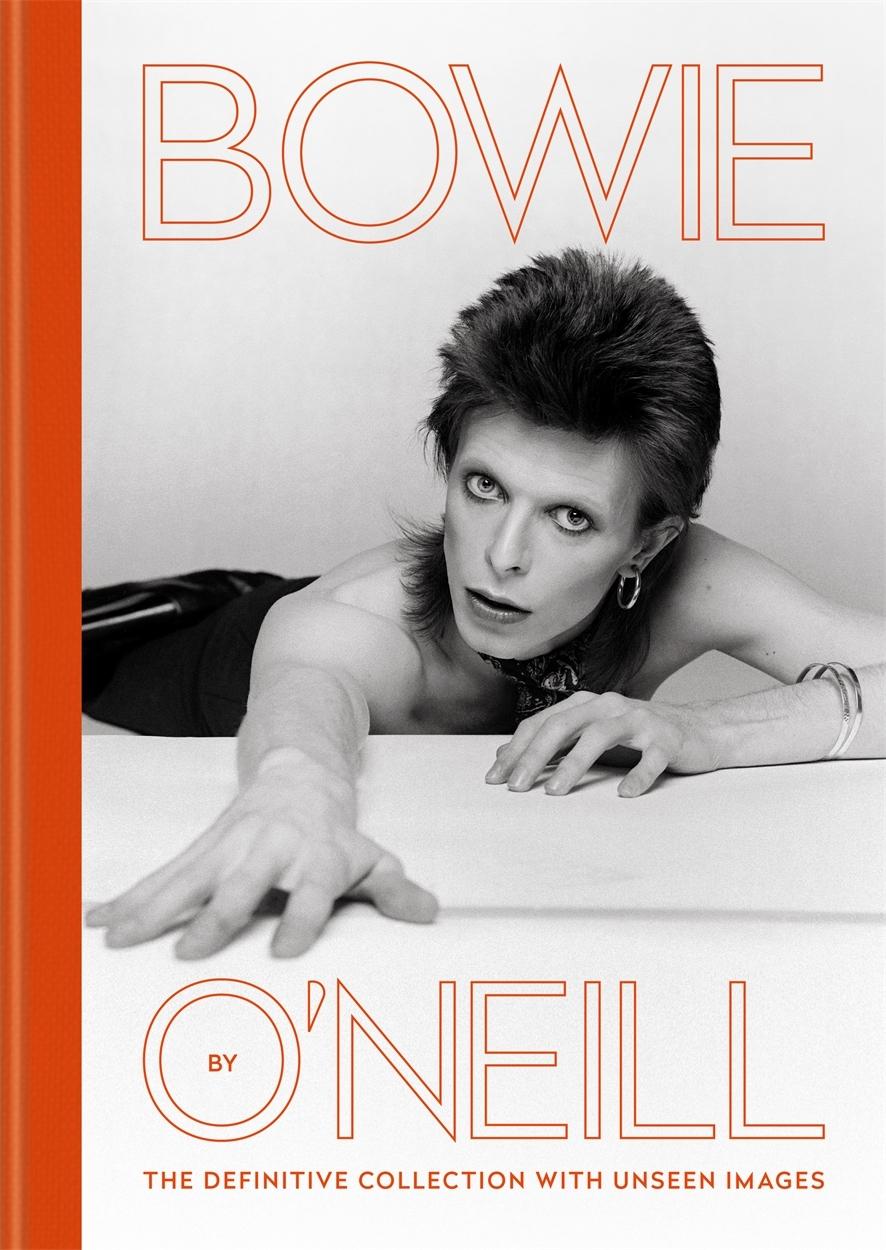

Bowie by O'Neill: The Definitive Collection with Unseen Images, by Terry O'Neill, published by Cassell Illustrated, £40 www.octopusbooks.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here