It is perhaps the first thing many people think of when they think of an artist – pencil in hand, sketching, a line on the page representing a form or an idea. Perhaps drawing is thought of as a starting point, a way of working through thought, a precursor to a painting or other work of art, a means of marking-up, pointing out. But a drawing is also an end-point, and it need not be in pencil or, for that matter, ink. Drawing, once a staple of art schools around the country, is no less fundamental now as a prime means of human expression, and this exhibition seeks in some way to trace its evolution and importance across three generations of contemporary Scottish artists, touching on its way everything from abstract art to jewellery.

“The starting point was a conversation with Diana Sykes at Fife Contemporary,” says Amanda Game, a freelance curator, who says Sykes has a wonderful ability to work across disciplines. Game has herself long been interested in drawing, from the 20 years she spent behind a desk at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh, where she saw “a lot of different kinds of drawings, as well as work from craftspeople and designers.” Since she left, in 2008, she tells me she's had a wider exposure to different kinds of work, resulting both from contact with different arts and crafts organizations and from research for her subsequent MPhil at the Royal College of Art in London. “I found Tim Ingold's book, “Lines – A Brief History,” absolutely fascinating. It shifted my understanding of all the different ways we make marks, from design drawings to music to handwriting.”

In 2018, Game wrote a short piece for the catalogue to the “A Fine Line” exhibition at the City Arts Centre in Edinburgh which brought together four contemporary artists working in different disciplines in an exploration of the line in art. “That really focused my mind,” says Game. “I became aware of just how many people are thinking about drawing, and thought how interesting it would be to look at it – not going out and commissioning new pieces, not saying “this is contemporary art,” but looking back over the last 30 years in Scotland and just asking a question. The conceit is that I'm only half in Scotland these days, so I thought it was rather like if somebody sent letters from Scotland, but they all came in the form of a drawing, what would it tell us? What would it tell us about Scottish culture more widely?” And then Game laughs and says, “that sounds a bit grand!”

Grand or otherwise, there is a wide range of work in the exhibition, from the late 1970s to the modern day, from John Houston to Hanna Tuulikki. Game, thinking widely, broadened out into other fields which use drawing, from botanists drawing the fine detail of newly discovered plants to archaeologists drawing the detail of a 1 metre square patch of land as they excavate down through the millimetre layers of history. “I phoned people up and asked, does drawing still really matter in your field, in these days of technology and photography? The resounding answer was “Yes!”,” she says.

Botanical drawings and its permutations are writ large in the exhibition, not least as part of the wider theme of landscape which is a key interest in drawing in Scotland in the last 30 years, says Game. But these are not necessarily “straight” examples. Hanna Tuulikki's work, which melds the idea of musical notation and botany, is one example. Elizabeth Blackadder, famed for her flowers and cats, features, but in a rather less known example of her portraiture. “I found a rare portrait she'd done of her husband John Huston in 1956, the year she was married,” says Game – rare both as a Blackadder portrait, and as a portrait of her husband. It turned out Huston had done one of Blackadder that same year and both will show in the exhibition, alongside an equally rare “cityscape” of North Bridge in Edinburgh, by Blackadder.

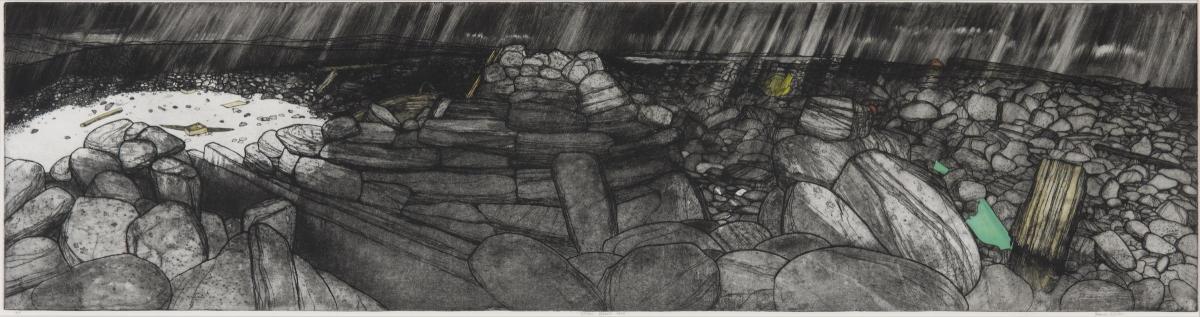

The older generation is represented, too, by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham in one of her St Andrews drawings from 1981, a cityscape from the sea full of rhythmic waves. Here too, is Vortex, a representation of the power of wind and wave in line. Dorothy Hogg, the jeweller, represents drawing as something three dimensional “in sand and wire”, says Game. “She had a passionate commitment to drawing as a field of discovery and exploration.” Deirdre Nelson and musician Inge Thomson's work translating the landscape and knitting patterns of Fairisle into music will be on show, alongside works from Andy Goldsworthy, Ian Hamilton Finlay, David Shrigley, Susie Leiper Frances Priest, amongst others. It is a cross disciplinary exercise in fine detail, in close observation. “We're not reinventing anything, but reflecting back,” says Game, who tells me the installation of all these detailed works next week is going to be the tricky thing. “It's really just the tip of the iceberg.”

Lines from Scotland, St Andrews Museum, Kinburn Park , Doubledykes Road, St Andrews, www.fcac.co.uk 01334 474610 9 Nov - 22 Feb 2020, Weds to Sat 10.30am-4pm Then touring to Dunfermline Carnegie Library & Galleries (7 Mar-10 May 2020) and Gracefield Arts Centre, Dumfries (16 May-25 July 2020).

Critic's Choice

The Scottish Gallery has long been associated with Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, the Scottish artists who set up studio in St. Ives, Cornwall in 1940 and remained rooted there until her death in 2004. Representing the artist in her life, and after, the gallery here presents this retrospective of her later career, beginning in 1958, when the artist was working through rigorous abstraction to a more fluid and organic approach to colour, form and textural expression. Wide-ranging, eclectic, Barns-Graham never stood still, experimenting with intensity of colour, with contrasting forms or geometries, with precision or with freedom of mark-marking.

Born in 1912 in St. Andrews, Barns-Graham went to Edinburgh College of Art before moving to St. Ives, in Cornwall, where she became lifelong friends with Bernard Leach, Robert Borlase Smart and Ben Nicolson, with poet WS Graham and Barbara Hepworth, alongside many other artists and writers. Overlooked during much of her lifetime, as were many twentieth century women artists working in an art world dominated by men, she once recalled being unwilling to let Nicolson know where she had been sketching in Italy because “it would be me that would be told I was influenced by Ben.” She was once mistaken by a leading London gallerist, despite talking with him on art for many hours, as “the wife of Willie Barns-Graham.”

But Barns-Graham persisted, her evolving work from her 40s onwards traced in this exhibition from the wonderfully free and fluid forms of the late 1950s work inspired by her trip to the Balearics to the intensely colour-saturated discs of her mid-career, the textural collages of her 70s and the late printmaking with the Graal Press, well into her 80s.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: A Journey Through Four Decades, The Scottish Gallery, 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, 0131 558 1200, www.scottish-gallery.co.uk 30 Oct – 26 Nov, Mon – Fri, 10am – 6pm; Sat 10am - 4pm

DON'T MISS

The Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh may be closed for refurbishment - although you can find their fabulous shop temporarily set-up in the Waverley Mall on the opposite side of the train tracks - but it is not closed for business, as evidenced in this weekend exhibition of the results of their school art programme at Custom Lane in Leith. Working with eight primary and secondary schools from around the capital, pieces include responses to the gallery's 2019 festival work, "Night Walk for Edinburgh" by Janet Cardiff and George Bures-Miller. Pupils have created plaster casts of the Old Town, overlaid with graffiti, or made soundscapes of their school, or worked in film to produce responsive installations - do get down to Leith, if you can, to see the results of this inspiring programme.

Follow In Our Footsteps: The Fruitmarket Gallery’s Making Matters and SmART Thinking Schools’ Programmes Exhibition,

Custom Lane, 1 Customs Wharf, Edinburgh, www.fruitmarket.co.uk Sat 26 Oct 10am-5pm, Sun 27 Oct 11am–4pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here