Tim Taylor is obsessed, he tells me, with the stuff around us. From recycling to household appliances, his art, often witty, encompasses everything from a household iron melting through a block of ice (roughly 30 minutes, in case you're wondering) to a circle of non-circular saws and the “abstract origami” of used bus tickets. He has recorded the dropping of his daily tea bag from an 8 foot height to the floor below, and car indicators flashing in and out of time. His stuff is the beauty and pathos of the everyday. His latest work, currently being installed in the Custom Lane gallery space in Leith, takes the recycling we throw out – specifically packaging – deconstructs it, and makes prints from it. “I've been flattening this stuff for years!” he grins.

Taylor has been collecting packaging – much to his wife's chagrin, he tells me - for the past 8 years. “It was a joy getting them all out. There is just so much interesting stuff on these boxes – the textures, the lines, the folds and so on.” He is interested in the marks, not of the corporate brands, but of the glue that binds the unbound pieces, the folds that define the final form. Once, particularly, tactile nobbles of Braille. Each carton makes its own mark.

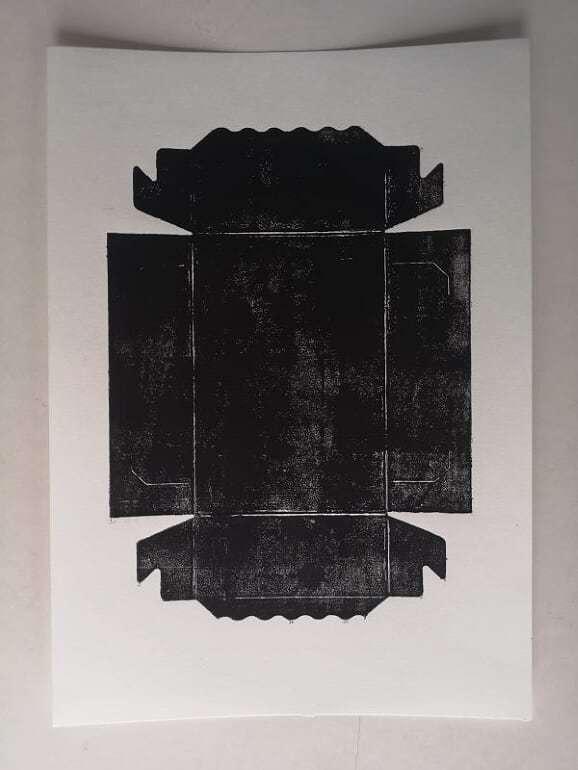

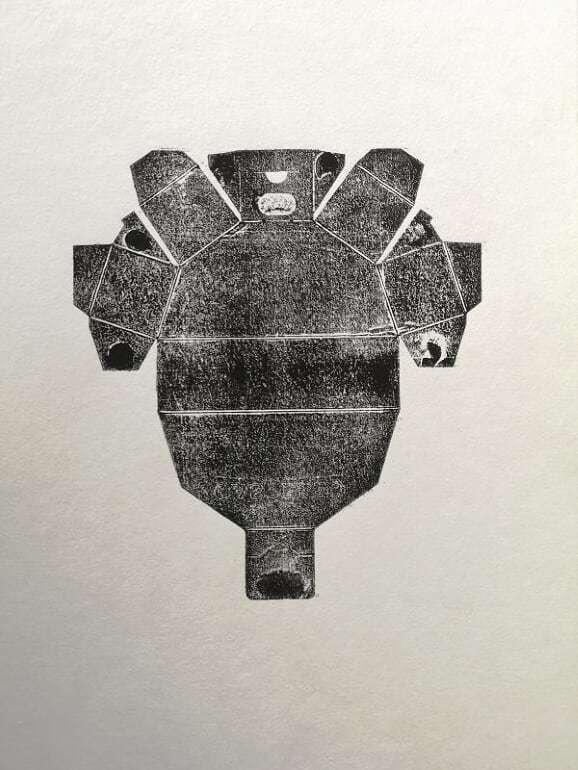

And not all are created equal, which Taylor only discovers when he takes each one apart to its flat-pack form. The black and white prints bring every form into relation with another, the structures printed in the middle of the paper, mounted on the walls, all 108 of them (although he has a few more in reserve) as a grid. Black, gritty, the shapes are frequently unrecognisable, demanding to be decoded, a blocky sci-fi Rorscach army released from the recycling box under the sink.

“There's a typology when you group them together. When I started photographing them, keeping a record, I got quite excited about seeing them all together,” says Taylor. He was reminded, he says, of Bernd and Hilla Becher's Water Tower photos, their Gas Tanks, their Blast Furnaces, each series taking an architectural type and photographing it in black and white, the form central, “a more or less perfect chain of different forms and shapes,” as they once said. Taylor's own series Sacred Vessels (2018), which may be shown again as part of ArchiFringe in 2021, was a matchstick model homage.

Taylor's other day job is at Groves-Raines Architects, housed in an annexe of the 16th century Lamb House just over the river from Custom Lane – no flat-pack houses here. But Taylor has been working as an artist since graduating from the Architecture School of Edinburgh College of Art, ensconced in his WASPS studio, occasionally moonlighting in the arts venue Summerhall when he needs somewhere more local. His work, too, has included a number of public commissions in health centre settings, not least at Maryhill where he created a series of wonderful miniature worlds to e seen through a peephole in a wall or clear tile in the floor. Last year, one of his earliest and most popular film works, Domestic Erosion (a witty and pointed triptych of household appliances melting an ice block) was shown as part of an experimental music festival in Berlin, slowly melting on the walls as an Australian jazz band played a four hour non-stop set.

Taylor has gone back to age old Japanese printmaking practice for these works, flattening out the box, rolling the ink over it, lining it up, laying paper on top and then rubbing over it with a bamboo baren – essentially a nub of wood that you burnish prints with. “I did all these on a bench, they're all hand printed which kind of opens up a bit of the manual process, and introduces a bit of chance...”

He has his favourites, notably a hoummous carton, “with holes so the pot goes in,” he says. “The simple ones folded in one direction. They're very minimalist!” he says. The unfolded, printed shapes encompass all sorts, he grins. “The ones I've gravitated to personally are less flappy! More blocky!”

The darkness of it all will be lightened by a series of colourful felt tip pen sculptures, the lids stacked vertically. All are leftover from dried up felt tips given to his children over the years. More stuff. At heart this is an observation, says Taylor, on how much of this stuff passes through our lives.

Tim Taylor: Dark Interiors, Custom Lane, 1 Customs Wharf, Leith, 0131 510 7571 customlane.co Until 2 Feb, Mon – Fri, 9am – 5pm; Sat, 10am – 5pm; Sun 11am – 4pm

Don't miss

This latest exhibition at Dundee Contemporary Arts is rooted in the work of the brilliant Ursula K Le Guin, whose 1969 novel, “The Left Hand of Darkness”, also lends its name to the show itself. The ideas in this work of feminist science fiction, set on an ice planet whose name translates as “Winter”, revolve, amongst other things, around the shifting gender of the inhabitants of Gethen. Curators Eoin Dara (DCA) and Kim McAlese (Programme Director at Grand Union, Birmingham) use Le Guin's ideas – from politics to environmentalism and feminism - as a springboard for this international exhibition, which reassesses ideas brought up by Le Guin's groundbreaking works in a group exhibition that will continue to change and shift as the winter passes.

Seized by the Left Hand, Dundee Contemporary Arts, 152 Nethergate, Dundee, 01382 432 444 www.dca.org.uk, Until 22 March 2020, Daily 10am - 6pm

Critic's Choice

Underneath the vast range of works holding court in the airy gallery rooms upstairs, Calum Colvin RSA gets the basement rooms to himself for this celebratory retrospective/highlights show of the artist's work. It coincides with the publication of a new book by Tom Norman, The Constructed Worlds of Calum Colvin: Symbol, Allegory, Myth, studying Colvin's photography, and celebrating 40 years of the artist's working life. Known for its complexity, its range of references, its wit, Colvin's photography takes centre stage in the exhibition, its subject matter ranging from the everyday to the art historical.

Born in 1961 in Glasgow, Colvin studied at Sculpture at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, before going on to the Royal College of Art in London, graduating in 1985, Colvin's recent work looks at the issue of Scottish nationalism and identity, but also Scottish culture, contemporary society and the thrust of human ambition. If Colvin's work is full of research, it is also often humorous.

Colvin is well know for his complex constructed photographs, which address the formal parameters of the image in asking the viewer to essentially construct the image themselves. The roots of this stage setting are partly to be found in his early interest in sculpture. Colvin overpaints his tableaux of household objects with ideas and gleaning from myth or popular culture, leaving a photograph of parts that requires attention and interpretation. Colvin might perhaps help with this on 22nd January, when he himself will lead a gallery tour.

Calum Colvin, Royal Scottish Academy, Academicians Gallery and Finlay Room, Princes Street, Edinburgh, 0131 624 6110, www.royalscottishacademy.org Until 2 Feb, Mon – Sat, 10am – 5pm; Sun, 12pm – 5pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here