The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood

Sam Wasson

Faber & Faber, £18.99

WHERE and when does a movie begin? How far back can you trace its origins? How close can you get to the source?

Take Chinatown. Do we trace it back to writer Robert Towne reading Chandler and getting nostalgic for the Los Angeles he remembered as a kid? Or him watching developers tearing up the land around his home in LA’s Hutton Drive waved through by city hall?

Or do you go back further to the Second World War and the Jewish ghetto in Krakow where Chinatown’s eventual director Roman Polanski spent his childhood and from where the Nazis took his mother?

Or maybe, like every other crime story, we start with a murder. Maybe we go back to an August night in 1969 when Charles Manson’s followers broke into a house on Cielo Drive and murdered the five people they found inside, including Hollywood actress Sharon Tate, Polanski’s pregnant wife.

In The Big Goodbye, author Sam Wasson explores all these tributaries and more in telling the story of the 1974 movie about crime and corruption both financial and moral in 1930s LA. Wasson in the past has written about Audrey Hepburn and the choreographer Bob Fosse. Here, he argues that Chinatown is one of the last gasps of the New American cinema of the 1970s before the blockbuster bulldozed in and took over the neighbourhood.

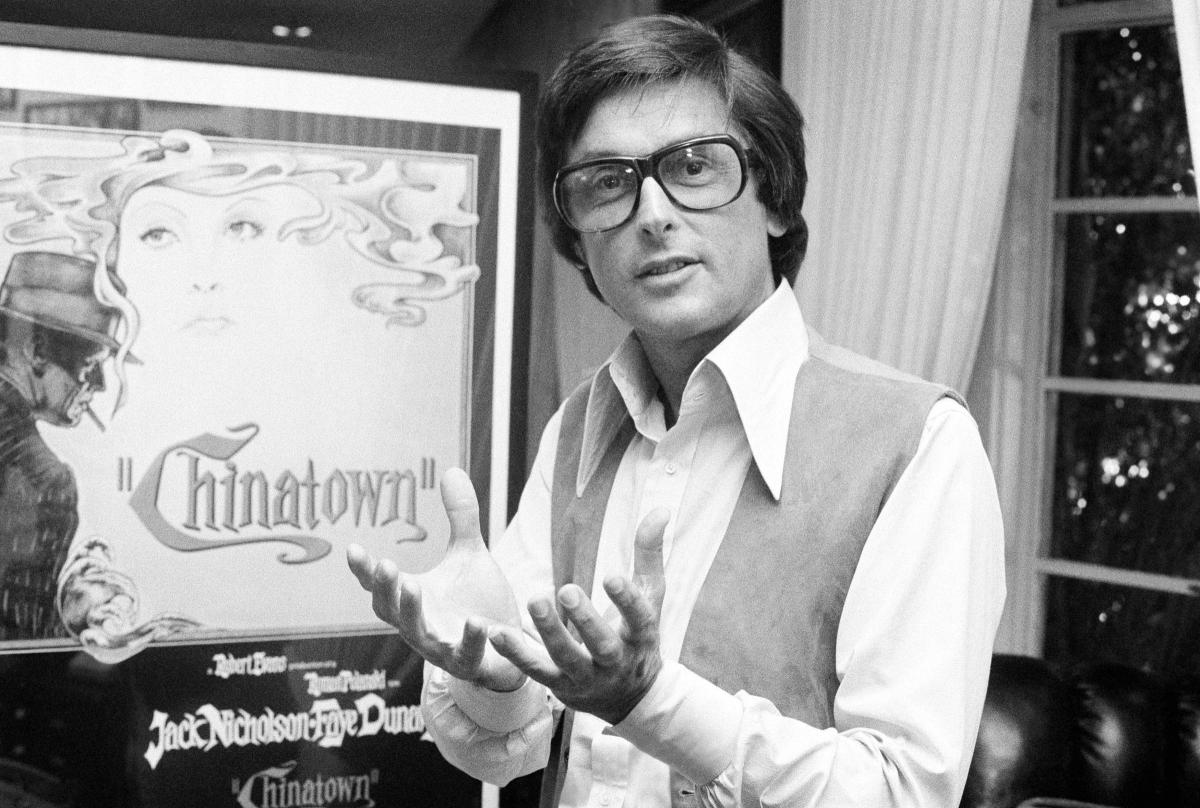

He locates Chinatown’s story within the lives of four of its main participants, adding the stories of its star Jack Nicholson and its producer Robert Evans to those of Towne and Polanski. Nicholson was the coming man, an actor who had shared a flat with Towne, was the star of The Last Detail, written by Towne, and someone who felt he owed Evans a favour. Evans was enjoying his status as the man who saved Paramount, after a run of hits including Rosemary’s Baby, The Godfather and the hugely successful Love Story.

Evans saw in Chinatown a chance to combine Hollywood traditional glamour with artistic integrity and he was prepared to push Towne’s desire to direct to the side as a result. Polanski, meanwhile, had come to believe, from experience, that there was no such a thing as a happy ending and kept pushing against the romanticism of Towne’s script. Hard to see how else he could have reacted given what happened to his wife.

Wasson deals with the murders of Sharon Tate, Abigail Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Parent and Jay Sebring sparingly. At the same time, he refuses to look away from the horror of it. As a reminder of what happened it shows up the callowness of Tarantino’s counterfactual take on that night in last year’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

The senseless murders of that summer marked an end of innocence for the hippy idyll of the 1960s (Altamont was still a few months in the future). Strung out on grief, Wasson reports, Polanski turned himself into a detective in its wake. He would sneak into friends’ garages and swab their cars for fingerprints. He bugged their homes. He’d even surreptitiously checked Bruce Lee’s lens prescription against that of a pair of horn-rimmed glasses found at the scene of the murder.

There were no lessons to be drawn from the murders, Polanski would say. “There is just nothing. It’s absolutely senseless, stupid, cruel and insane. I’m not sure it’s even worth talking about. Sharon and the others are dead. I can’t restore what was.”

That nihilism followed him through to the making of Chinatown a few years later. Shooting started with casting not finished and no agreed ending. The film’s female lead, Faye Dunaway, quickly made herself unpopular with crew and her director. At one point Polanski pulled an errant hair from her head which was ruining his shot. It didn’t go down well. Nicholson had it easier, although Polanski did end up chucking Nicholson’s TV out of his trailer during a Lakers game when the actor wouldn’t present himself for a set-up because he was trying to catch the end of a game.

No wonder, then, that Nicholson was worried Polanski was to be the one who was to “slit” his nose with a prop knife that had to be sliced in the right direction in one of the film’s most notorious moments. Polanski shot 12, maybe 14 takes. He’d got the shot he wanted on the first.

Evans was the man who had to placate everyone. Including Towne who was seeing his romantic vision darkened, his story tarnished.

But maybe he shouldn’t have been surprised. America was going through Watergate, the fag end of the Vietnam war, an oil embargo. Nihilism, understandably, was in. As the film’s last line has it: “Forget it Jake, it’s Chinatown.”

Wasson corals all this with energy and commitment. His style – at times overblown, reaching for effect, seductive for that very reason – is obvious from the first line after the introduction: “Sharon Tate looked like California.” If you respond to that, then this is for you.

Wasson’s argument is that 1974-1975 was a pinch point for Hollywood. The last hurrah for the American version of auteur cinema; the kind of films Evans produced and Polanski directed. In 1974, the year Chinatown was released, so were Alan Pakula’s The Parallax View, Robert Altman’s Thieves Like Us, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and Steven Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express, movies that were ambitious, adult, arty.

Spielberg’s next movie, Jaws, would change the current, opening in hundreds of cinemas rather than trying to build an audience as had been the release pattern before. It worked. Spectacularly.

Soon the blockbuster was key. TV execs began to take over Hollywood’s studios and the appetite for ambitious, adult and arty began to recede. Deal-making took over from film-making, Wasson argues. There were still ambitious films ahead: Altman’s Nashville, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, but the tide was going out. And Star Wars was waiting in the wings to change everything. Who wants auteurs when you can have franchises?

Wasson’s book is a lament for a style of movie-making that is no longer in favour. It has not, despite the book’s elegiac tone, disappeared though. Martin Scorsese kept making movies and, in the years that followed, American directors such as Michael Mann, Kathryn Bigelow, David Fincher and Paul Thomas Anderson would all emerge.

Still, the film ecology did change. It keeps changing. Chinatown the movie is now as distant from us as it was to the 1930s. It stands as a reminder of how Hollywood once was.

Wasson wants us to believe that Chinatown is a heroic achievement. But he doesn’t hide away from the fact that there are no real heroes in this story. Towne’s reputation soared after Chinatown but so did his appetite for drink and drugs. Evans’s, by contrast, took a huge hit with the failure of The Cotton Club. And Polanski? He pleaded guilty to statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl in Nicholson’s house and then fled to Europe. Some things you should never forget.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here